- Stay Connected

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

The WWII Crash of C47 ‘Lilly Bell II’

Published on: 20 Apr, 2012

Updated on: 4 Jun, 2012

The military aircraft that crashed in a field at Hurst Farm, Jacobs Well, Guildford, on October 25, 1944, killing its four-man crew, received little attention in the local press at the time. Until the latter part of the war, reporting such incidents affecting allied aircraft would probably have been banned by the censorship rules.

In 1999, when David Rose and Graham Collyer were writing their book Guildford The War Years 1939-45 (Breedon Books), they could find no details of the crash except a brief report that appeared in the Surrey Times newspaper days after the incident happened.

A few years after the book was published, local and aviation historian Frank Phillipson contacted David Rose saying that he would be

interested in trying to find more details about the crash. Now,

with Frank’s meticulous research and David’s support, the full story

has been uncovered.

The research project has been an amazing “journey” putting Frank and

David in touch with many people who have helped in one way or another.

The research project included consulting records from both Britain and America, the tracing of the families of the crew in the US, an appeal for eye-witnesses to the crash, magnetic geophysical survey, and metal detecting and an archaeological dig at the crash site.

There was also a successful appeal to raise money to place a memorial plaque to the four airmen near the crash site and its subsequent unveiling in 2010. Frank and David wrote a number of articles for David’s history page, “From the Archives”, that he then edited for the Surrey Advertiser.

During 2011, Frank continued with the research and now, with a good deal more information, the full story appears here for the first time. Being on this website, it means any new facts that come to light can easily be added.

So, sit back and read Frank’s words of The Crash of “Lilly Bell II”.

Brief news item that appeared in the Surrey Times. The other Guildford newspaper at the time, the Surrey Advertiser did not report the incident.

How the crash happened

The Surrey Times of Saturday October 28, 1944, briefly reported: “A Dakota crashed in a field in Clay Lane, Jacobs Well, on Wednesday morning and burst into flames. The National Fire Service from Guildford put out the flames with foam and recovered four mangled and charred bodies.”

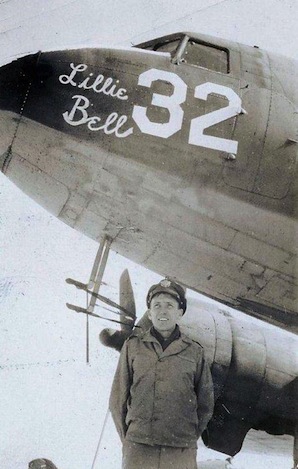

The aircraft was a US Army Air Force, Douglas C47a Skytrain (known as a Dakota when in RAF service), Serial No.42-100766 named “Lilly Bell II”. It belonged to the USAAF’s 89th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS) part of the 438th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) based at Greenham Common, Berkshire. “Lilly Bell II” was individually coded as aircraft “D” of the 89th TCS and carried the Squadron code of “4U” on the fuselage behind the cockpit.

It was loaded with 5,120lbs of signal equipment including a large amount of “field wire” which had all been lashed down and balanced within the aircraft.

On the morning of Wednesday, October 25, four C47’s took off from Greenham Common and formed a diamond formation with “Lilly Bell II” in the right-hand position behind the lead aircraft.

The four men on board were: pilot, 28-year-old 1st Lieutenant Mercer Wilson Avent; acting co-pilot, 32-year-old Flight Officer John Edmund Wright; crew chief/flight engineer, 21-year-old Technical Sergeant John R. Hillmer; radio operator, 21-year-old Staff Sergeant Dale E. Dellinger.

The formation’s destination was the northern French airfield at Denain / Pouvry (code number A83) south east of Lille near the Belgian border. The weather that day in southern England was total cloud cover at about 1,000ft height and visibility of 2,000yds. Flying below the cloud level, the formation’s route would entail clearing the 600 foot high North Downs. As they flew from west to east they approached the high ground just after 11am.

The formation commander decided to lead the four aircraft up through the cloud.

What happened next is best described by the pilot of the rear aircraft of the formation, 2nd Lt. Harry E. Watson: “The last time I saw him (Avent) he was at approximately 1,300ft and was climbing in an effort to go up through the overcast. His aircraft seemed to be in trouble. It appeared that Lt. Avent’s ship would collide with my ship, so I dropped the nose, opened the throttle and got out of the way. I then lost sight of him in the clouds, and our formation continued on its flight.”

What happened next is best described by the pilot of the rear aircraft of the formation, 2nd Lt. Harry E. Watson: “The last time I saw him (Avent) he was at approximately 1,300ft and was climbing in an effort to go up through the overcast. His aircraft seemed to be in trouble. It appeared that Lt. Avent’s ship would collide with my ship, so I dropped the nose, opened the throttle and got out of the way. I then lost sight of him in the clouds, and our formation continued on its flight.”

It appears that Lt. Avent may have seen a gap in the cloud and climbed too steeply to get through it. The aircraft then either stalled and/or the load in the fuselage shifted rearwards leaving it momentarily vertical.

It then did a tail slide dropping straight down until the tail surfaces developed enough lift to bring the nose down. The aircraft, now upside down, then dived towards the ground. At such a low height the pilot had no chance of regaining control or the crew any chance of baling out.

The aircraft crashed into a field about 85 yards north of Clay Lane’s present-day junction with Queenhythe Road at Jacobs Well, two miles north of Guildford, Surrey.

The engines, propellers and nose section became buried in the ground while the centre and rear fuselage together with the wings remained on the surface.

Fire broke out upon impact and much of the forward and centre section were burnt out despite the efforts of the National Fire Service. They could do nothing for the crew who would have all been killed in the impact.

Basil Gorton lived with his parents in Jacobs Well and was home on leave from the Black Watch at the time. He saw the C47 struggling in the air and then go into a dive and crash. Sometime later he went round to the field and saw the wreckage and cables strewn about and a number of bodies under a tarpaulin.

Douglas Graham, then aged 10 and living half a mile to the south, heard about the crash and hurried up to the crash site on his bicycle.

He remembers standing in Clay Lane looking into the still smouldering fuselage. An American airforce officer was visible sifting through the wreckage. In his hand he had a map or large notepad of some sort.

A guard was initially mounted on the wreckage by one NCO and nine men from the Queen’s Royal (West Surrey) Regiment. The RAF and the USAAF were informed and the latter came to the scene to guard the site, recover bodies, remove the wreckage and investigate the accident.

The bodies were removed and taken to an out station of the Connaught Military Hospital Aldershot at Brookwood. The four airmen could only be identified by papers found on them and by the fact that they had taken off in the aircraft. The bodies were conveyed to the temporary US military cemetery near Cambridge and buried.

The USAAF then started to clear the wreckage. Neil Davis, who was aged about nine at the time and lived a few hundred yards from the crash site, remembers that they had lifting equipment and trucks to take everything away.

Mary Smithers, who was also a Jacobs Well youngster at the time, remembers that American servicemen guarded the gateway to the crash site from Clay Lane. She recalls that they gave her the first chewing gum she ever had and the excitement she felt at Americans being in the village.

On November 6, a “wind valve” and on December 4 a propeller blade from the aircraft were found on Stringers Common not far from the crash site to the west.

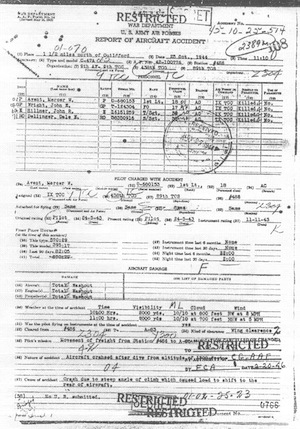

The USAAF accident report stated that the rear binding ropes securing the load were found to be broken but that it was not possible to determine whether this occurred in the air or upon impact. The report concluded that the pilot had made an error in trying to get the aircraft to climb at too steep an angle.

The field at Jacobs Well as it looks now. Note the poplar trees on the horizon. Similar trees can be seen in the crash photos.

History of the 438th TCG and C47a, 42-100766 “Lilly Bell II”

Three of the crew of “Lilly Bell II” killed in the crash, namely Avent, Hillmer and Dellinger had operated the aircraft from when it had been allocated to them in the US. The aircraft had been named “Lilly Bell II” after Avent’s wife’s maiden name Lillian Bell.

The 438th TCG (which in England in February 1944 was to become part of the 53rd Troop Carrier Wing, 9th Troop Carrier Command of the US 9th Air Force) had been activated at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana on June 1, 1943. It was made up of the 87th, 88th, 89th and 90th Troop Carrier Squadrons.

It moved to Sedalia Field, Warrensburg, Missouri on June 9, 1943, where it started flying with just a few old commercial airliners. It trained to drop paratroops, tow gliders, evacuate casualties and to carry freight either to be dropped or from airfield to airfield.

Final intensive training was carried out from October 30, 1943, at Pope Field, Camp Mackall, North Carolina and Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base, North Carolina.

From January 15, 1944, the Group moved back to Baer Field prior to flying across the Atlantic to Britain. To make this possible the aircraft were fitted with additional internal fuel tanks.

The crew that flew “Lilly Bell II” to England were: Pilot, 1st Lt. Mercer W Avent; Co-pilot, 1st William J Foster; Crew Chief, Sgt. John R Hillmer; Radio Operator, Pfc. Dale E Dellinger; passengers, 1st Lt. Joseph A Riggs; Cpl. Donald E Riley; Cpl. Michael W Niga Jr.

On January 28, 1944, the 438th TCG aircraft started in stages to leave Baer Field for Morrison Field, West Palm Beach, Florida. From there they flew to Borinquen Field, Perto Rico; then to Atkinson Field, British Guiana and then Belem Brazil.

From here the aircraft flew two different routes to Dakar, Senegal.

The first route was via Adjacento Field, Fortaleza, Brazil; Acension Island and Roberts Field, Liberia. The second route was via Natal, Brazil and Fernando Island, Brazil.

From Dakar the aircraft flew to Marrakesh, French Morocco in early February.

From Marrakesh the aircraft took off and flew up the coast of Portugal and then on a wide course away from the French coast across the Bay of Biscay.

The aircraft landed at RAF St. Mawgan in Cornwall or RAF Valley on Anglesey.

From these airfields the Group flew on the February 16 to RAF Langar (Station 490), Nottinghamshire which was to be their first base in England.

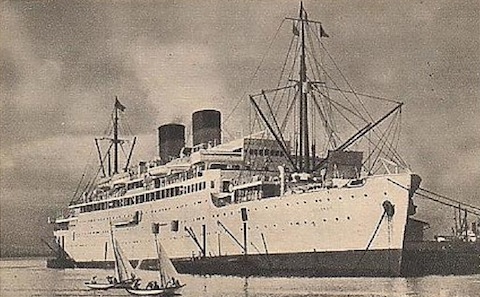

On February 2 the 438th TCG glider pilots, ground crew and other ground based personnel left Baer Field by train for New York. On February 26 they boarded the former French 13,391 ton liner “Columbie” which sailed the next day.

On March 9 the “Columbie” anchored on the Firth of Clyde and the next day docked near Glasgow. March 11 saw the men disembarked and taken by train to RAF Langar.

On March 15 the 438th moved to RAF Greenham Common (Station 486), Berkshire.

This airfield had many aircraft concrete hardstanding areas added as well as pierced steel planking areas laid to accommodate the many aircraft and gliders required for D-Day. Heathland to the east of the airfield was used to assemble the US Waco CG-4A assault gliders from packing cases. They would then be towed across to Greenham Common either for use there or to be towed to other airfields.

Before D-Day the four squadrons of the 438th TCG were involved in training including overload takeoffs and landings, formation flying, dead reckoning navigation, ascent and decent through low cloud and night flying. Dropping paratroops and towing gliders was also practised in addition to transporting freight around. With flying in England they also became proficient in coping with bad weather.

The formation used for paratroop dropping consisted of a “Vee” of nine aircraft formed by three smaller “Vees” of three aircraft each.

The training culminated in Operation “Eagle” on the night of May 11 over the Berkshire Downs which was a dress rehearsal for D-Day. Because of their excellent performance in this exercise the 438th TCG was chosen to lead the US aircraft dropping paratroops on D-Day.

On May 15 men of the US 101st Airborne Division started training the glider pilots of the group in ground tactics for when they landed.

The C47s were modified with armour plate added to the pilot and co-pilots seats and the whole of the crew were issued with flak jackets. The pilot and co-pilot were issued with .45 calibre pistols and the crew chief/flight engineer and radio operators with a carbine each.

A few days before D-Day, the airfield was sealed off with barbed wire and armed guards. All airforce and paratroop personnel were confined within. The C47s and gliders had 24inch wide black and white “invasion stripes” hand painted overnight around the wings and rear fuselage to identify them as Allied aircraft to friendly forces.

General Eisenhower visited Greenham Common on the eve of D-Day on the June 5 to talk to the airborne troops and aircrews before watching as they took off. The 438th TCG, using 72 C47s from its four squadrons (18 aircraft per squadron) and nine C47s of the attached 71st TCS of the 424th TCG, were the lead unit to drop paratroops north of the Normandy town of Carentan.

They carried 1,430 men of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion all from the 101st Airborne Division.

“Albany” was the code name for the 101st Airborne drop and was part of Operation Neptune the assault part of D-Day. Overall the US 9th Air Force contributed 821 C47s to the initial paratroop drop.

These troops were to secure the flanks and areas behind the landing beaches to prevent German units directly reinforcing the defending troops on the coast.

After crossing the English Channel at 500ft towards the Channel Islands the C47s turned to fly from west to east across the Cherbourg Peninsula. This route was designed to avoid as much as possible the German anti-aircraft guns. The route thereafter was planned to avoid flying over the Allied invasion fleet. Only the lead aircraft of each formation had a navigator and radio navigation aids. The other aircraft had to formate on these aircraft.

After rising to cross French the coast at 1,500 feet the aircraft dropped down again to between 500-700 feet and reduced speed to around 110mph to allow the paratroops to drop.

The following report extract outlines the 438th part in the operation:

“Take-off, first plane 22:23, last 22:56. Landing, first plane 02:10, last plane 02:45. Over drop zone from 00:48 till 00:58 – altitude 700 feet. Weather scattered clouds and slight ground fog. Visibility 3 to 4 miles at drop zone. Scattered ground fire and light flak encountered. Mission very successful.”

Although there was low cloud and ground fog, the 438th was not affected as much as following formations and as the first aircraft of the airborne invasion did not encounter as much enemy fire as later formations.

Following the D-Day paratroop drop, the group carried out reinforcement glider towing mission to Normandy in the late afternoon of June 6. This was mission was code named “Elmira” and carried men from the 82nd Airborne Reconnaissance Platoon, 82nd Airborne Signal Company, 82nd Airborne Divisional HQ and the 307th Airborne Medical Company. They were carried in 14 Waco CG-4A gliders and 36 Horsa gliders. As the German forces were now aware of the invasion the 438th came under increased amounts of ground fire.

Flight Officer John Wright, as a glider Co-Pilot, flew a reinforcement glider flight carrying infantrymen and mortar bombs on the morning of June 7 with the 434th TCG based at Aldermaston to which he had been temporarily transferred. The 434th TCG towed 50 Waco CG-4A gliders containing men from the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, glider artillery and engineers to reinforce the 82nd Airborne Division in Normandy as part of Mission “Galveston”.

The 438th TCG received a Distinguished Unit Citation for spearheading the fleet of paratroop aircraft on D-Day – “approaching their objective at low altitude and at minimum airspeed, through adverse weather conditions and strong anti-aircraft fire”.

After D-Day when not carrying out airborne operations, the group flew freight supplies to the US Army in Normandy. On their flights back to England they carried casualties including stretcher cases. They had to land at improvised airfields with poor surfaces that were not always really large enough.

In July, most of the group comprising the 87th, 88th and 89th Troop Carrier Squadrons, departed for Italy to take part in the invasion of the South of France (Operation Dragoon).

“Lilly Bell II” took off from Greenham Common on the July 18 bound for Canino airfield 60 miles north-west of Rome. With long range fuel tanks fitted internally they initially flew to Gibraltar. Flying on from there they landed at Canino on July 21.

Initially the Group flew orientation and training flights. On August 18 the squadrons of the 438th Group took off from early morning (02.10 onwards) loaded with 638 men of the 1st Battalion of the US 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment as part of Operation Dragoon code named Mission “Albatross”. Flying across the Mediterranean they dropped these men in the vicinity of Le Muy in the Argens Valley inland from the seaborne invasion between Marseilles and Cannes.

On return to Canino the aircraft then towed gliders to the same area to reinforce the paratroops. Flight Officer John Wright, as a glider Co-Pilot, flew one of these reinforcement glider flights carrying a doctor, medics, medical supplies and a jeep trailer.

“Lilly Bell II” left Canino on August 23 for Marrakesh. It arrived back at Greenham Common on August 31.

By September 1944 the Allies were advancing through France and Belgium but were unable to use Channel ports for supplies either because they were still occupied by German troops (the Allies bypassed these towns) or had been rendered unusable. This meant that all supplies for the advancing Allied armies had to be brought over the Normandy beaches and trucked through France over shattered roads. As the distance increased it became progressively more difficult to get enough supplies to the armies.

To make up the shortfall it increasingly fell to the Allied C47s to fly in supplies of food, ammunition and fuel, etc, to former Luftwaffe airfields that had been repaired. This became a daily occurrence often with crews flying two trips to the continent a day in all but the worst weather. They would return to England with casualty evacuations. To add to the pressure the whole crew would often assist in unloading and loading.

On average US C47s were delivering around 2,000 tons of supplies a day mostly comprising fuel with each aircraft carrying 120 individual five-gallon Jerrycans.

On September 17, 1944, the 438th dropped men from the 1st Battalion and Headquarters Company of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division near Eindhoven. This was part of the Allied operation Market Garden which attempted to push into Holland up the road to Arnhem to outflank the German army. Towing of glider reinforcements took place on following days.

On September 17, “Lilly Bell II” and her crew dropped men from the 101st Airborne near Eindhoven and on September 18, 19 and 23, towed gliders to the same location.

Flight Officer John Wright piloted a glider to the Eindhoven area on D+2 (September 19) carrying a gun, ammunition and airborne troops.

After landing, John Wright saw a C47 crash in a manner eerily similar to “Lilly Bell II”. In a letter home he describes what he saw: “At this point my eye was caught by a tug (aircraft) which was in a complete stall and at that time I expected it to spin but he fell off in a beautiful wing over and started a partial recovery but then went back to a straight dive. The rest you have seen in movies but this was my first sight of the real thing and it gives you a sort of weak feeling. It just doesn’t seem possible to me for a big ship like that to do that.”

Following the involvement in the airborne assault in Holland the air resupply and return casualty flights resumed.

The use of glider pilots as co-pilots on C47s was used as a way of relieving the stress on pilots and co-pilots engaged in the intense resupply and casualty evacuation flights. It also allowed Glider Pilots to get additional hours of flight experience.

Personal histories of the men killed

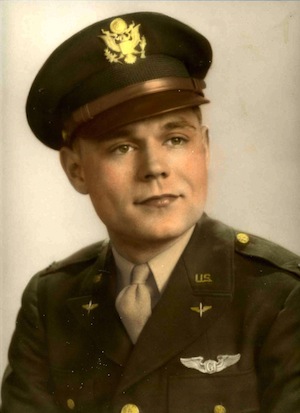

1st Lieutenant Mercer Wilson Avent

In command of the aircraft was 28-year-old 1st Lieutenant Mercer Wilson Avent, in civilian life a shipping clerk, from the town of Rocky Mount, North Carolina. He entered the army in July 1941 at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and by May 1943 had become a pilot. On December 24, 1943, at the Post Chapel, Fort Bragg, he married Lillian Bell, who was also from Rocky Mount, and after whom the aircraft was named.

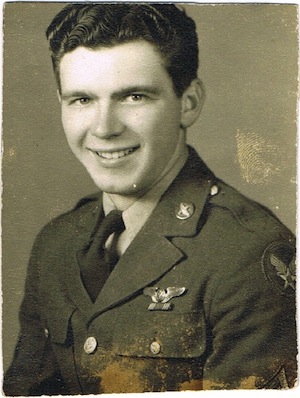

Flight Officer John Edmund Wright

The co-pilot was 32-year-old Flight Officer John Edmund Wright, originally from Nichols Village, Tioga County, New York State. He had attended Cornell University and was a member of the reserve officers’ training corps in the early 1930s.

He was employed by the International Business Machine (IBM) Corporation at Endicott, New York State, when in March 1942 he enlisted in the US Army Air Corps.

He held a pilot’s licence and flew a light aircraft but because he was over 30 the USAAF would only train him as a glider pilot.

He started training as a glider pilot in July 1942, graduating and being made a Flight Officer in December 1943. He was married in 1942 to Jean Irene Love, a school teacher of Endicott, NY, and they had a son, John Curtis Wright, born while he was stationed in Lubbock, Texas.

The USAAF created the rank of Flight Officer (effectively a 3rd lieutenant) so that NCOs trained as glider pilots would have commissioned officer status. In the USAAF, glider pilots were posted to the airforce squadrons that would tow the gliders and were not fighting troops as such.

Assigned to the 89th TCS of the 438th TCG at Greenham Common, Flt.Off. Wright was temporarily transferred before D-Day to the 434th TCG at Aldermaston not far to the east of Greenham Common.

Early on June 7, 1944, the 434th TCG towed 50 WACO CG-4A gliders containing men from the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment and glider artillery and engineers to reinforce the 82nd Airborne Division in Normandy as part of Mission “Galveston”. Flt.Off. Wright co-piloted one of those gliders taking off at 4.50am. After they had landed, the glider pilots were to make their way, as soon as possible, back to the landing beaches and England.

His Normandy service earned Wright the Air Medal for outstanding gallantry. The citation for the medal stated: “Magnificent spirit was displayed by this officer and combined with skill, courage and devotion to duty, remained at the controls of the glider without regard to personal safety against most severe enemy opposition and landed his glider.”

Wright also landed gliders during the invasion of the South of France and operation Market Garden in Holland.

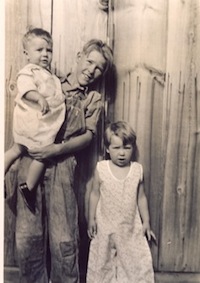

Technical Sergeant John R. Hillmer

Technical Sergeant John R. Hillmer was a 21-year-old, from Wayne County, Detroit, Michigan. He was the crew chief/flight engineer, was single and (according to airforce records) had been an aircraft fabric and dope worker just before joining up.

John (known as Jack to his family) was one of six children of John and Catherine Hillmer of 13496 Eureka Avenue, Detroit. He graduated from St Augustine School and was employed by the Bull Dog Electric Company which made electrical switchgear. He joined up in November 1942.

His family have some amateur movie film of John on his one and only leave at home before going overseas. It shows him dancing, laughing and having fun with his sister Lucille (Mitzi), and at the end of the film saluting to the camera.

Staff Sergeant Dale E. Dellinger

Staff Sergeant Dale E. Dellinger was a 21-year-old from Springer Town, Colfax County, New Mexico. He was the radio operator, was single and at the time of his enlistment was an aircraft and engine mechanic on the production line at Consolidated Aircraft Corporation in San Diego, California.

Burials and personal effects of the crew

By mid 1945 the next of kin of the airmen were receiving the personal effects left in their quarters at Greenham Common and personal items recovered from the bodies.

Some items of three of the crew had been damaged by the fire and to avoid unnecessary distress the relations were asked if they wanted them included.

They all replied that they did. No mention is made of any damaged items in correspondence with Dellinger’s relatives although these appear burnt as well.

In February 1947, the families were all sent a photograph of their respective husband’s or son’s temporary grave.

In March 1947, they were all asked whether they wanted their loved one buried in a new permanent US military cemetery at Cambridge, or brought back to the USA.

The Wright and Dellinger families both asked that their men be buried in England.

The Hillmer family requested that his body be returned to Detroit for burial. This was done and John R. Hillmer now lies in the Mount Olivet Cemetery, Detroit.

The Hillmer family have a framed case containing John’s medals, ribbons, cap and a plaque together with a telegram that his mother received informing her of his death in an “airplane crash”.

All that the family knew about his death was that it occurred in a crash during a routine flight and was not due to enemy action. They were told that the crash occurred at “Farnsborough” (Farnborough), the place name quoted on all the documents, presumably because of unfamiliarity with English geography by the US personnel.

His mother and sister Lucille (Mitzi), went to New York to see a serviceman who had known John. Two of his siblings, Bernice Pellegrino and James Hillmer still survive (2010).

Difficulty was encountered in trying to contact Lillian Avent to establish her wishes. Through various channels it was not until July 1948 that is was established that she was seriously ill and unable to complete the form.

Meanwhile in January 1948, Avent’s father wrote to ask that his son’s body be returned to the USA. In August, he was informed that as Mercer Avent’s wife was the next of kin, it was up to her to make the decision, but that if she decided to relinquish her rights, those rights would pass to him as the next in line of eligibility.

In an effort to discover what her wishes where, on November 19, 1948, Captain Vogl of the Quartermaster General’s Department, was finally able to contact Lillian Avent by telephone.

She said that she wanted her husband to be buried in England and asked for more details of how her husband met his death. However, Vogl told her that he could not help as the information was not on the file.

He advised her to contact another branch of the Army Air Force. In January 1949, Lillian Avent died of breast cancer and probably never found out the circumstances of her husband’s death.

Headstones of the four airmen. From left: Avent, Wright, Dellenger (at Cambridge), Hillmer (in Detroit).

Crash site investigation

Aviation historian Simon Parry and local historian David Rose during an initial 'sweep' of the crash site with a metal detector in September 2007.

Part of researching the crash of the “Lilly Bell II” has been to find the exact crash site.

It was known that this was in the vicinity of Clay Lane in Jacobs Well north of Guildford. Wartime map references and maps put the location as being to the south of Clay Lane in the vicinity of what is now Stringers Avenue, but was then fields.

Poor quality photos (they were copied from the 16mm archive microfilm of the US crash report) of the wreckage showed what seemed to be a row of poplar trees similar to those on the north side of Clay Lane, near to and running parallel to the A320 Woking Road and which still exist today.

Using this, together with two witnesses to the site of the wreckage at the time, it was possible to get an approximate location.

Any excavation of military aircraft crashes in the UK requires a licence be obtained from the Ministry of Defence. Having supplied all the available information and evidence that the crew’s bodies had been recovered at the time, a licence was obtained.

An initial general metal detector sweep of the field only yielded iron and lead items; not really aircraft material!

The witnesses were again consulted and a more precise location identified. Upon investigation, a sweep of this area yielded a number of aluminium aircraft parts and a portion of cast aluminium crankcase and cylinder barrel.

This established a starting point for a more thorough gridded and recorded metal detector sweep by Discoverers, Guildford Metal Detecting Group. This was carried out on a Sunday in November 2008.

This revealed more aluminium aircraft parts some corroded to just white or light blue colour fragments or powder. Some burnt areas on the site were discovered with blackened deposits and melted aluminium parts.

A geophysical survey was later carried out by Surrey Archaeology Society to coincide with an isolated ploughed area (which was slightly east of the initial area investigated) shown on a 1947 aerial photograph. This ploughing was most likely done to level off and bury any remaining small debris from the crash. A large area of burning in this area is likely to have been the centre of the crash site. A few further aluminium finds were discovered in this area.

Altogether, the items recovered have been mostly unidentifiable apart from being typical of aluminium aircraft items, including small airframe parts and small sections of fuel pipe.

Some of the finds from dig, clockwise from top left: seatbelt buckle; bulb holder; aluminium operating arm; alloy component with an opening steel cap; part of crankcase and cylinder barrel; fuel sender unit; fragment of aircraft structure; Wittek Mfg Co Chicago, pipe clip.

Identified items include a 5in-diameter aluminium casting with an aluminium pipe attached which, from a C47 parts manual, was identified as a fuel level sender unit from a wing fuel tank. Also recovered were the back face of an instrument dial marked “Indicator” and “General Electric”, a rusted steel aircraft seat belt buckle, a parachute harness buckle, a fragment of engine crank case/cylinder and a damaged “Wittek Mfg Co, Chicago” pipe clip. As the witnesses to the clearance of the wreckage at the time observed, the USAAF seem to have been very thorough in its clean-up operation

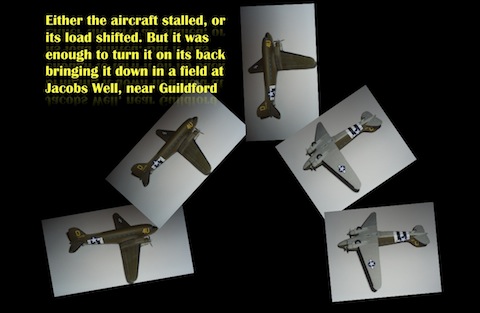

Scale model of “lilly Bell II”

There were well over 1,000 Douglas C47 Skytrain aircraft in use by the US Army Air Force in the UK in 1944.

The one chosen by model maker Corgi to reproduce as part of a limited edition set commemorating the 60th anniversary of D-Day was “Lilly Bell II”. The set included two US fighters namely a P-47D Thunderbolt and a P51D Mustang.

“Lilly Bell II” was probably chosen because of the existence of the photo of it at Greenham Common. However no-one at Corgi would have known the story of the aircraft.

Memorial plaque

A memorial plaque to the crew has been erected on a sandstone plinth at the junction of Clay Lane with Queenhythe Road. Paid for by local residents, companies and the local parish council it was unveiled in a moving ceremony by the son (also called John) of the co-pilot John Wright on Sunday, October 17, 2010.

Pictures from the unveiling ceremony featuring members of the Wright family from the USA who were guests of honour.

Aluminium fragments found at the crash site were added to the aluminum used in the manufacture of the plaque.

During the unveiling ceremony a flypast was carried out by C-47A 43-15211 based at Kemble and piloted by Andy Davenport.

Worplesdon Parish Council looks after the plaque, cutting the grass around it, and so on. The parish of Worplesdon does not have a war memorial as such, and on Armistice Day (November 11), 2010 and 2011, the parish council held a remembrance service and a two-minute silence at the plaque in memory of all those who have lost their lives during conflicts. Wreaths were also laid during the services.

The memorial plaque is near to the footpath beside Clay Lane, at the junction with Queenhythe road, Jacobs Well, Guildford. The field into which "Lilly Bell II" crashed is opposite.

Thanks to the following people (in no special order) for their special help with this project: aviation historian Simon Parry; Phil and Anne Vallis of Discovers Guildford metal detecting group; Dean and Davina Robinson of Hurst Farm, Jacobs Well; Worplesdon Parish Council and its chairman Bob McShee and parish clerk Gaynor White; piper Kenneth Thompson, who played at the memorial unveiling; eyewitnesses to the crash Douglas Graham, Basil Gorton, Mary Smithers and Neil Davis; Professor John Wright (co-pilot’s son) and his family; Chris Heywood of the Surrey Archaeological Society (SAS); David and Audrey Graham of SAS for the Geophysical survey; Andrew Davenport of Wings Venture for the flypast by C47 43-15211 at the unveiling; Traci Thompson, Local History/Genealogy Librarian at Braswell Memorial Library, Rocky Mount, North Carolina for help in tracing Avent family; Mary Kuznia of the Hillmer family Detroit; Marguerette Powell, Marilyn Meek and Mary Wildman of Dellinger family; individuals, companies and organisations who donated to the memorial plaque fund.

Recent Comments