Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Recalling The Excitement When The Beatles’ Love Me Do Was Released

Published on: 9 Mar, 2016

Updated on: 14 Mar, 2016

With the death of music producer George Martin announced today (March 9), former Guildford journalist Dave Reading recalls his first encounter with the music of the Beatles – describing how even the national music press were caught unawares by the rock ‘n’ roll revolution that was about to take place.

Back in ‘62, when Elvis was King, the highlight of the week for tens of thousands of pop lovers came on a Friday morning when their New Musical Express, or NME, arrived in the shops.

In those days the NME was published in a black-and-white newspaper format. Priced at sixpence, it was an essential read for anyone besotted with pop music, as most of us kids were. One of the pages we’d turn to first would be the NME Top Thirty because we’d want to know what everyone else was buying.

Each week you’d find the usual crop of brown-eyed boys in the charts, most of them US imports like Tommy Roe doing his Buddy Holly impersonation on Sheila and Johnny Tillotson with his jaunty Poetry in Motion. Music writers do not speak well of this phase in rock ‘n’ roll history. Cliff Richard had been a hero for some of us, but now he was being smothered in sugary, orchestral arrangements.

Normally the NME showed us what it was cool to like, but the paper’s coverage on October 19, 1962, was sadly out of touch with what was about to burst on the world music scene. The whole of the front page was devoted to a suave new songster called Chance Gordon – presumably space that had been paid for by his record company, which was normal in those days.

A picture spanning most of the width of the page showed him looking cool but easy-going in his dark suit as he leaned against a wall casually holding a cigarette. Inside on page 4, a brief review of his single, Instant Love, revealed that he’d been “discovered” by Adam Faith. The single flopped and Chance was never heard of again. Not by me, anyway.

The top sellers that week were the Tornados with their space age instrumental Telstar and Little Eva singing about a new dance craze, the Loco-Motion. Shirley Bassey was at No.9 with her standard pop ballad What Now My Love?

A new single recorded by an act from Liverpool went largely unnoticed at first. The group’s name was the Beatles. People must have cringed when they saw that – a daft name based on a bad pun.

The title of their single, Love Me Do, sounded like it might be a sentimental ballad in the style of Elvis’s Love Me Tender. Or maybe this was one of those novelty acts, like the Chipmunks. After a few seconds’ thought, people’s attention was diverted to the latest chart sensation, the Australian country yodeller Frank Ifield, who had a new single.

In Guildford, like most towns probably, there were a few kids who were ahead of the rest in terms of fashion and tastes in music. They were the first to wear the buttoned-down collars and the chisel toe shoes; the first to drop names like Muddy Waters into conversation.

One boy in our group – his name was John – had an older sister who kept him in the know, so he was the one we looked to for information on what to wear or what music to like.

John ridiculed my fondness for the Shadows and said my red tie was ridiculously out of fashion. John was the first of us to discover Love Me Do. He played it for us incessantly on his HMV record player in his bedroom in Westborough while I strummed along on my battered Rosetti guitar, which I’d bought for £6 at Buyers, the second-hand shop which stood at the bottom of North Street.

We turned to the NME for hot news about the Beatles. We learned about the likes and dislikes of the Tornados in a regular column called Life-lines. Clem Cattini admired the actor Lee Marvin but hated bad drivers; Heinz Burt was keen on fishing, home cooking and relaxing; Roger Jackson was a Glenn Miller fan and was fond of bacon and eggs; and so on and so on.

We didn’t know it, but the NME was in danger of becoming irrelevant. As readers chuckled at the thought of the organ player with the Tornados grooving to Glenn Miller over his bacon and eggs, things were happening up in Merseyside.

In the NME letters page, a guy from Yorkshire felt the Shadows had “improved immeasurably”; a London girl praised Jess Conrad’s “marvellous personality”. Reviewing the latest singles, Keith Fordyce homed in on Jimmy Dean (“ultra catchy tune”), Frank Ifield (“fast and lively performance”) and Connie Francis (“bouncy beat number”).

In the news pages, Princess Margaret was said to have noticed that Cliff Richard had a new drummer even though it hadn’t been announced. “I knew you had,” she told Cliff. “I could tell a difference in the beat.”

On the inside back page there were promotional ads for easy listening acts like Joan Regan and David Whitfield. Downpage there was a small advertisement announcing simply THE BEATLES in capital letters, with the name of their new single on Parlophone. That was their only mention – buried on page 11.

John told me to forget Cliff and the Shadows. He said things were changing.

Love Me Do didn’t get a lot of airplay but somehow it crept into the lower half of the Top Thirty. Once people got to hear it, they encountered the unexpected. What they heard was difficult to classify. If anything, it was related more to American R&B than pop, with its bluesy vocal style and wailing harmonica.

Some of us in Guildford were growing tired of mainstream pop and, thanks to the influence of people like my friend John, we were taking an interest in American black music: performers like Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf and Sonny Boy Williamson. The Beatles didn’t sound black, but Love Me Do did have the same raw edge.

Guildford High Street in a view from the mid-1950s. Music shop Barnes and Avis was on the right-hand side going up.

The weekend after the record came out, John bought an Echo Super Vamper harmonica for about ten shillings from Barnes and Avis in Guildford High Street. He tried to emulate the sound that John Lennon achieved on Love Me Do. He sucked and he blew while I strummed along in the key of G. The result was dire. But we had the beginnings of a band.

Although receiving little airplay, Love Me Do reached number 17 in the NME Top Thirty. What none of us knew at that time was what had been going on behind the scenes and the role George Martin had been playing. With the death of the Beatles producer on March 8, 2016, the world has been reminded of the huge role he played as the Beatles transformed popular music forever.

In later years Martin was endearingly honest in his admission that he didn’t get it at first. When he first heard the Beatles on a demo disc – brought to him by their manager Brian Epstein at Martin’s office in Manchester Square, London – he could easily have shown Epstein the door.

“The recording, to put it kindly, was by no means a knock-out,” he wrote 17 years later. “I could well understand why people (other record companies) had turned it down. Their material was either old stuff, like Fats Waller’s Your Feet’s Too Big, or very mediocre songs they had written themselves.”

As a producer at Parlophone, Martin had been used to working on comedy records like Bernard Cribbins’ Hole in the Ground, and was desperate to move on by finding a promising act in the pop world. He was jealous of the success others were having, in particular Norrie Paramor, his opposite number on Columbia, whose artist Cliff Richard had scored 16 Top Ten hits since 1958.

It wasn’t immediately apparent that the Beatles were the band Martin was looking for. “But… there was an unusual quality of sound, a certain roughness that I hadn’t encountered before,” he said. “There was also the fact that more than one person was singing, which in itself was unusual. There was something tangible that made me want to hear more.”

Even so, he believed the Beatles’ own compositions had no saleable future. He thought their success would lie in him finding suitable material written by established songwriters.

This was how things were done in the early sixties. Generally the groups recorded what was handed to them by the producers – songs written by polished professionals that reflected an overall image the label had in mind for them.

The number George Martin had in mind was Mitch Murray’s catchy but lightweight How Do You Do It? The Beatles were horrified and begged Martin to consider their own material but he stood firm… at first.

Eventually, despite his misgivings, Martin agreed they would record Love Me Do and see how it turned out. After he heard the result, the song grew on him.

He reached the conclusion, tentatively at first, that maybe he was listening to a chart hit after all. He has said it was Lennon’s harmonica that gave it its appeal, but it was the harmonies that transformed the two-chord verse into something remarkable.

The Beatles continued to push hard and George Martin listened to their pleading. This became one of the defining decisions in rock ‘n’ roll history. Love Me Do became the Beatles’ first single, released on October 5.

Legend has it that Brian Epstein, was wholly responsible for getting Love Me Do into the charts because allegedly he bought up boxloads, pushing them through his family’s store, NEMS, in Liverpool. But even if that’s true, it can only be part of the story.

There was a reaction elsewhere in the country too, as there was down here in Guildford. When the record came out there was a spontaneous outbreak of excitement, led by one or two teenage prophets.

This fervour was captured by my friend John when he raved about the Beatles in his bedroom in Westborough. And when their next single, Please, Please Me, was released, followed by their first album – all bearing the hallmarks of the George Martin genius – we were all hooked.

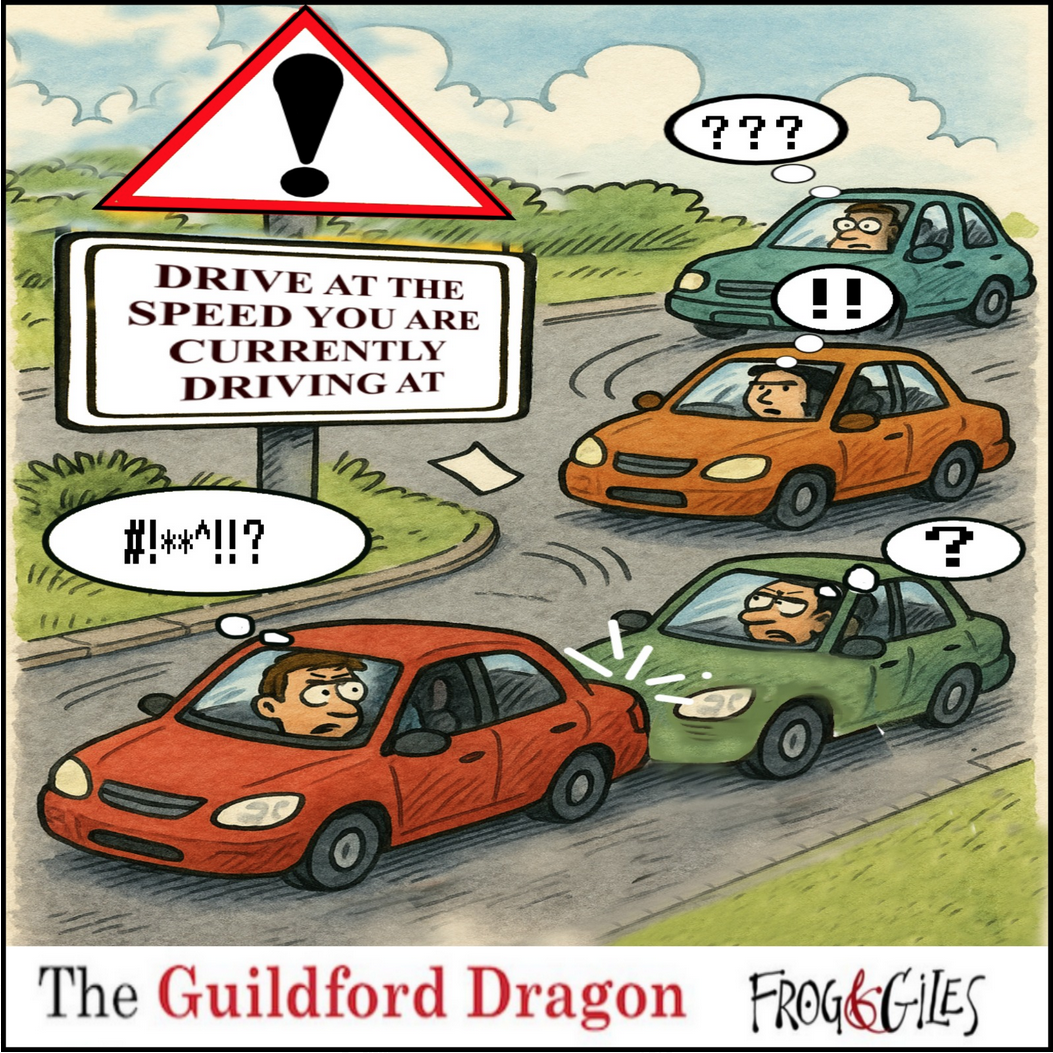

Click on cartoon for Dragon story: Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

Recent Articles

- Guildford Museum Works to Encourage Interest in Town’s History

- Missing 15-year-old girl located

- What Ash Wants – Village’s Neighbourhood Plan Goes out For Consultation

- St Nicolas’ Infant School Celebrates ‘Good’ Ofsted Rating

- Former Guildford Policeman Admits Misconduct In Public Office

- Letter: Nothing Prepared Me for the Scene of Destruction

- Have You Seen Missing Scarlet-Rose?

- Guildford’s MP Cuts the Ribbon at Merrow Post Office Opening

- Letter: Recreational Rowing Might Be the Answer

- A281 Closure – Additional Works To Take Advantage of Road Closure

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments