Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Feature: The Alchemist of Stoke – A Surrey Tale

Published on: 3 Sep, 2017

Updated on: 5 Sep, 2017

Nicholas Bale, in his story of artist and Guildfordian John Russell, mentioned Russell’s friend, alchemist James Price. Here is the full, sorry story as written…

by Guildford historian Matthew Alexander

Throughout history the lure of gold has led people onto every possible kind of foolishness. In particular, the notion that cheap, base metals could be turned into gold by a magical “Philosopher’s Stone” has enticed generations of men to spend their lives in pursuit of this ever-elusive substance.

Many of these alchemists claimed that there was a mystical, philosophic quest for truth, but there is no doubt that others were simply looking for a way of getting rich quickly. The fact that none ever succeeded – or none ever succeeded without trickery – did nothing to deter others from trying where their predecessors had failed.

The story of the alchemist of Stoke, however, has a number of unusual features. Firstly, he lived, not in the superstitious middle ages, but in the age of reason, when science was beginning to illuminate man’s knowledge of his world. Again, he was a wealthy young man, well educated and with good prospects, not not a confidence trickster needing to swindle gullible public for a living. The motives that drove him on his short life – and to his tragic end – will never be known for certain.

James Higginbotham was born in London in 1752 and graduated from Oxford when he was 25. In 1781, however, something happened that was to changes life utterly. His uncle, James Price, died, leaving him a fortune on the understanding that he adopted the surname of Price.

And so it came to pass that the wealthy young James Price, MA, bought a small country estate in Surrey, at Stoke, just to the north of Guildford. In his house he set up a well equipped laboratory, intending to devote much of his time to his hobby of chemistry. He sufficiently impressed the established scientists of his day to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, the foremost scientific society in the land.

His researches, however, were out of keeping with the spirit of the age. The new scientific reasoning relied only on observable facts, not the unsupported theories of ancient writers. Price, on the other hand, eagerly read the books of the old alchemists, and convinced himself that they contained an element of truth. In particular, he thought that mercury, silver, and gold were all forms of the same substance, and that a suitable catalyst would transform one into the other. This catalyst, of course, was none other than the ancient alchemists “Philosopher’s Stone”.

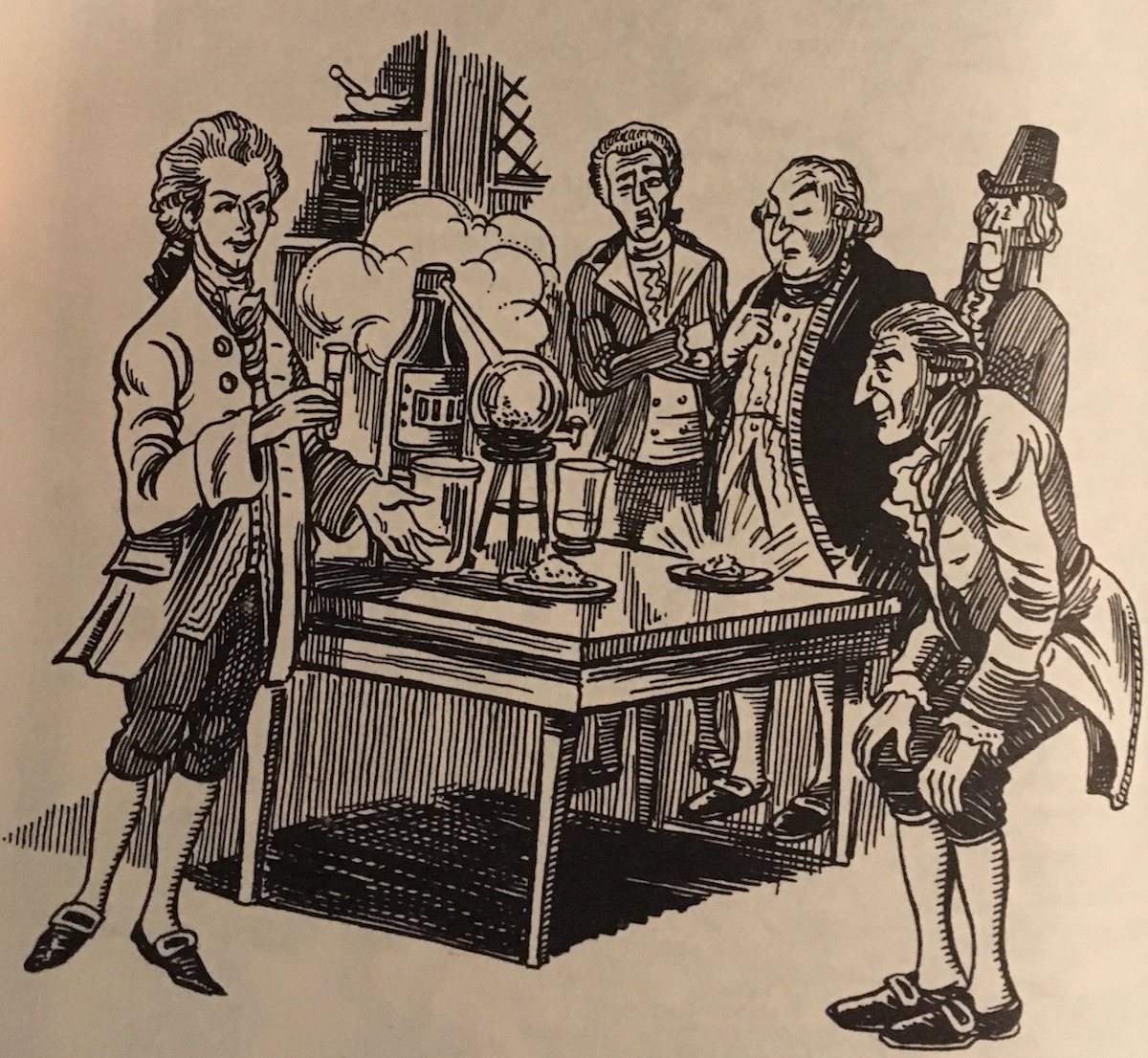

He revealed his discovery to an astonished world in May 1782, by holding a series of demonstrations…

Price set to work, and within a year he claimed to have discovered the secret in the form of two powders a white one which turned mercury into silver, and a red one which turned mercury or silver into gold. He revealed his discovery to an astonished world in May 1782, by holding a series of demonstrations witnessed by increasing numbers of the local gentry and the nobility.

Various substances were heated with mercury in a crucible, the magic powder added, and, before the very eyes of the onlookers, small amounts of gold or silver were produced. Price insisted on having a sealed sample of the gold analysed and sure enough it was found to be pure, genuine gold. However, his eagerness to prove there was no trickery might itself have aroused suspicions, just as a conjurers reassuring patter never convinces the audience entirely.

This story is taken from Tales of Old Surrey (normally available at Guildford Museum) and republished with kind permission of the author Matthew Alexander.

Not surprisingly, the experiments caused a sensation; first around Guildford, then in London, then throughout the country. The King himself, George III, personally inspected and approved specimens of the wonderful gold, and in July James Price MA was made Doctor Price by his university.

However, sceptics and cynics was soon pouring doubt on his results and his motives. When he published an account of his experiments later in the year, Price felt obliged to answer his critics. No deceit was possible in front of such reliable witnesses, he claimed, nor did he stand to make any money personally; not only did it cost him £17 to make £4 worth of gold, in any case he already had all the money he needed. But he obstinately refused to reveal the composition of the magical powders and his secrecy annoyed everyone.

Those who believed him thought he was selfish; those who did not, thought he was a crook. His friends – and they were getting fewer – urged him to tell the truth, and suggested that he might have been innocently mistaken by using mercury brought from guilders and so contaminated with gold. Price refused to admit he was wrong, however, and promised a full explanation – which never appeared.

Resentment of his attitude was felt nowhere more keenly than in the Royal Society, whose reputation was being tarnished by the young charlatan. The president, the formidable Sir Joseph Banks, summoned Price and demanded that he repeat his experiments in front of expert scientists – or face expulsion from the society and disgrace.

Dr Price return to Guildford early in 1783 to prepare a fresh series of experiments – and to make his will. He seems to have spent the next few months in despair. He must surely have known all along that his claims were at best mistaken, at worst fraudulent, and that inevitably he would be exposed.

Eventually he invited a deputation from the Royal Society to his house at Stoke and on 3rd August 1783 three respected scientists arrived to witness the controversial experiments with their own critical eyes. Dr Price welcome them and led them to his laboratory, where he invited them to inspect the apparatus. As they bent over the crucibles and furnaces the three chemists heard a gasp and a thud behind them. Spinning round, they saw Price lying at their feet, an empty bottle of prussic acid in his hand. He was stone dead.

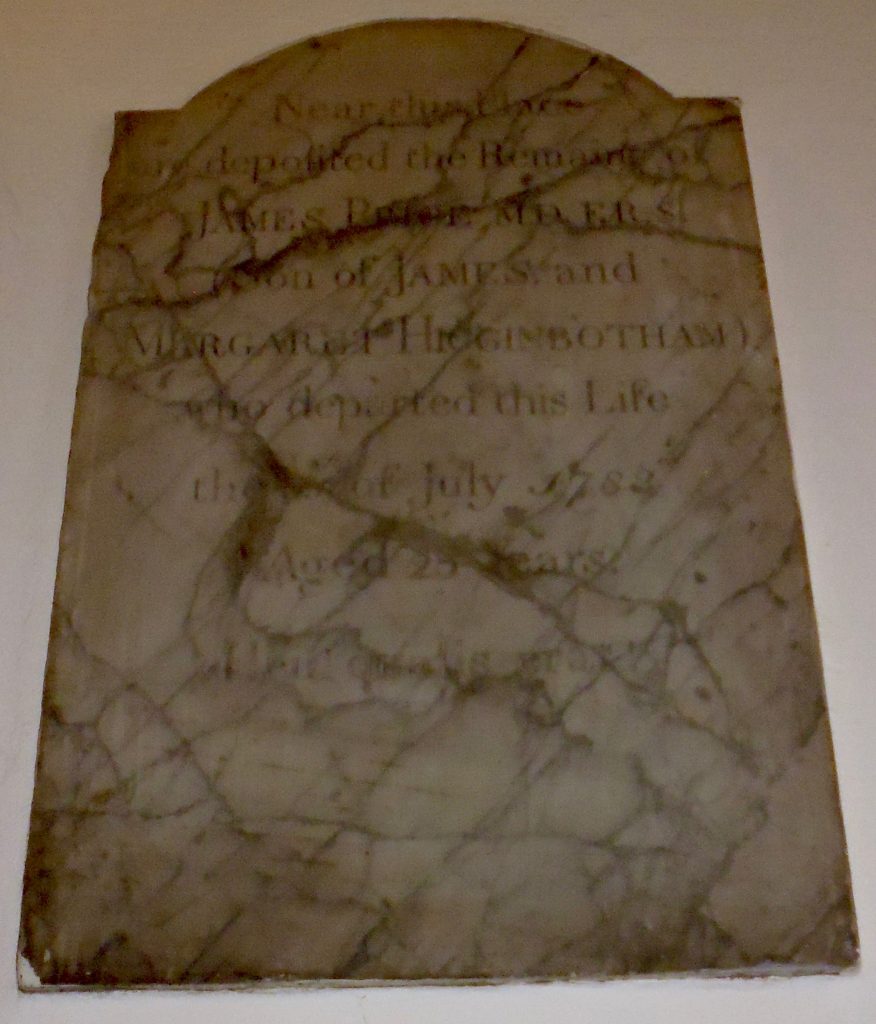

The memorial tablet to James Price is still to be seen above the south door of St John’s Church, Stoke.

So ended the short but remarkable career of the Alchemist of Stoke. The inquest judged him insane, and so not guilty of suicide – there was also a suggestion that he was entitled to Christian burial, and this he received at Saint John’s church nearby.

The memorial tablet to him is still to be seen above the south door. Ironically, it gets both the date of his death and his age wrong, but the short Latin epitaph is appropriate, whatever kind of man may he have been.

“Dr James Price FRS… Heu! qualis erat” – This can be translated as: “Alas, what a fellow he was,” or alternatively, “Oh, how mistaken he was!”

And then there were seven. (See article: "Lib Dems Remain Puzzled By Leader’s Decision to Sack Executive Member")

Recent Articles

- Birdwatcher’s Diary No.343

- City Defeated by Horley Hat-trick

- Man Dies Following Collision in Sutton Green – Police Appeal for Witnesses

- Letter: Waverley Council Should Keep Its Word

- Heritage Group to Challenge GBC’s Planning Approval for Clandon Park House

- Opinion: Attendance Is Only One Measure of Councillor Performance

- Letter: Lib Dems Should Take a Long, Hard Look at Themselves

- Letter: Poor Roadwork Management is Emblematic of Surrey

- Rising Flames Defeat Panthers

- Panthers Douse Flames

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Cllr Townsend on Waverley’s CIL Issue

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on Cllr Townsend on Waverley’s CIL Issue / Read MoreMP Zöe Franklin Reviews Topical Issues

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on MP Zöe Franklin Reviews Topical Issues / Read MoreMP Hopes Thames Water Fine Will Be ‘Final Nail in Its Coffin’

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on MP Hopes Thames Water Fine Will Be ‘Final Nail in Its Coffin’ / Read MoreNew Guildford Mayor Howard Smith

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on New Guildford Mayor Howard Smith / Read MoreA New Scene for a Guildford Street

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on A New Scene for a Guildford Street / Read MoreDragon Interview: Sir Jeremy Hunt MP on His Knighthood and Some Local Issues

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on Dragon Interview: Sir Jeremy Hunt MP on His Knighthood and Some Local Issues / Read MoreDragon Interview: Paul Follows Admits He Should Not Have Used the Word ‘Skewed’

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on Dragon Interview: Paul Follows Admits He Should Not Have Used the Word ‘Skewed’ / Read MoreDragon Interview: Will Forster MP On His Recent Visit to Ukraine

August 27, 2025 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Fiona Davidson on the ‘Devolution’ Proposals for Surrey

August 27, 2025 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments