- Stay Connected

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Remember, Remember The Guildford Guy Riots

Published on: 28 Feb, 2012

Updated on: 21 Jul, 2020

by David Rose

This summer’s riots across the UK shocked us all. However, this kind of behaviour is, unfortunately, nothing new. In the mid-19th century Guildford witnessed a number of riots that bear uncanny similarities to those in 2011.

One obvious difference, however, is that back then those who took part in the violent disturbances did not loot shops to steal items. They broke the law by removing wooden fences and other things to hand and burning them on huge bonfires, while, with their whipped-up emotions, venting their anger with violent attacks on anyone caught in their wake. This included the incredibly small local police force at the time which tried (often unsuccessfully) to disperse the rampaging mob.

Year after year the Guildford Guys made their appearance every November 5, and on other dates too. So, when you are out celebrating Guy Fawkes Night this year, spare a thought for those unfortunate Guildfordians caught up in the Guildford Guy Riots.

I wrote about these riots in my book ‘Guildford Our Town’, published by Breedon Books in 2001. This is the same version as appeared in that book.

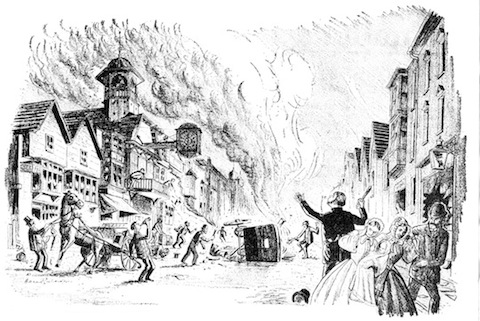

A somewhat fanciful illustration of one of the Guildford Guy Riots. Featured in the book ‘Guildford Our Town’ by David Rose.

Remember, remember the 5th of November. In the mid-19th century law-abiding Guildfordians certainly did, for it was the one day in the year they absolutely dreaded.

On Bonfire Night out would come the Guildford Guys to wreak havoc in the town – lighting fires, damaging property, letting off fireworks and even attacking innocent bystanders.

In the years following Guy Fawkes’ failed attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605, the event has been marked across Britain with bonfire parties and fireworks. In the early 1800s the tradition was somewhat on the decline, so many towns formed special societies to keep it alive.

Certain parties in Guildford were keen to celebrate as well, but as the years rolled on they became increasingly boisterous and mischievous. By the 1850s the events can only be described as blatant hooliganism, on a scale that today would see police officers in full riot gear and full coverage by the media.

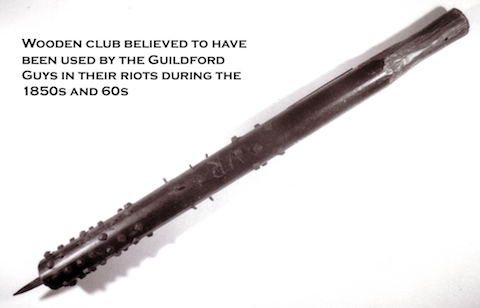

During the 1852 Bonfire Night troubles, several hundred people congregated in the town, many armed with bludgeons, their faces blackened. For several hours they rampaged through the streets. Afterwards, two Guildford clergymen wrote to the town council to complain, demanding compensation for damages to their properties which, they said, were caused by the mob.

When the council refused they took the case to the Home Office, which in turn demanded an explanation from the Mayor of Guildford, William Taylor.

To put it bluntly, Guildford was told to put its house in order and stop the riots forthwith. And although the town council was as keen as anyone to rid the streets of the Guys, tackling the problem was going to be a difficult one as there were few policemen.

There was a plan to enlist special constables to boost the town’s regular force, which in 1851, numbered just three constables and a superintendent. There may have been plenty of volunteers that year, but many failed to turn up for duty when the trouble was about to begin.

The 1850s were a bad decade for rioting in Guildford around Guy Fawkes Night. A huge bonfire would be lit outside Holy Trinity Church with smaller ones in places such as at Star Corner and even on the Town Bridge.

The official reading of the Riot Act was the only way to finally disperse the mob. Dating from 1715, it stated that a riotous group of 12 or more who failed to disperse within an hour of being ordered to would be regarded as felons. Anyone failing to comply could be arrested and expect harsh punishment.

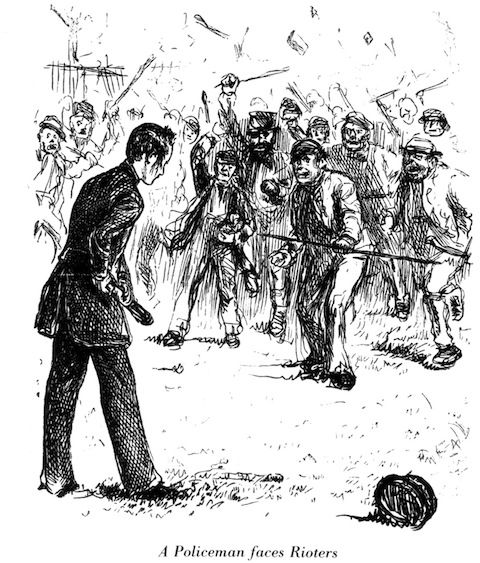

During the 1857 riots the Guys lit a bonfire outside St Nicolas Church. The police charged and were met by a hail of stones. In the melée one officer lost an eye. Two bystanders were hit by missiles and another was flattened by a group of policemen, although he was only trying to get his children out of the danger zone!

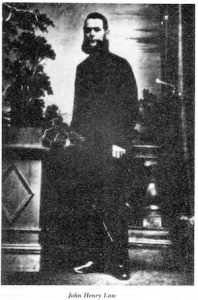

Police Superintendent John Henry Law armed his men with cutlasses. This helped to put at end to the rioting. Picture published in ‘The Guildford Guy Riots’ by Gavin Morgan.

The years rolled on yet the situation did not improve. Although many people feared for their own safety and their property, it was as if, on the whole, the town encouraged Bonfire Night and all its traditions.

The crowd cheered the 45 Guys who made their appearance in 1860. They wore a multitude of disguises and some were armed. One wore a helmet-shaped white hat with horns; another wore a sugar-loaf hat made of tin foil. A simple black mask covered the face of another, while one Guy’s mask consisted of tufts of wool. One even dressed as a woman!

The Surrey Times newspaper estimated that there were 1,000 spectators who watched the bonfires while suffering the indignities of Guys rushing up to them and demanding money. The event continued until 2am when a lighted tar barrel was kicked around the High Street.

By 1862 the mayor, Henry Piper, was making moves to put a stop to the yearly disturbances. He begged the Home Office to introduce an Act of Parliament that would give magistrates the power to hand out stiffer sentences to people caught letting off fireworks, lighting bonfires, or even wearing disguises in public.

However, it was to take his successor, and for Guildford to gain a terrible reputation following two incidents in 1863, that ended the Guys’ rein of terror.

During the evening of March 10, 1863, when the town, like the rest of the country was celebrating the marriage of the Prince of Wales to Princess Alexandra, a gang of Guys lit a bonfire outside Holy Trinity Church and smashed the windows of a house in the town. The news of this unprovoked event and that of a drunken riot at St Catherine’s Fair in October, when about 30 people were injured, spread further afield.

The Times newspaper printed a savage attack on Guildford.

The mayor was advised to bring in troops from Aldershot to prevent that year’s November 5th celebrations dragging the town down further.

Under the command of Lt Col Grey, 150 men of the 37th Foot, and 50 men of the 1st Royal Dragoons, were dispatched. It seemed to do the trick and the Guys soon dispersed.

Everyone wondered what would happen when the soldiers departed. But this wasn’t to be Mayor Piper’s problem. While the troops remained, for the next week or so, his term of office came to an end and the new mayor, Philip Whitington Jacob took up the reigns. He was determined to put an end to the riots.

On November 18, 1863, 151 special constables were sworn in to relieve the troops. Jacob grouped them into zones placing them in parts of the town where they could easily be summoned if trouble broke out.

The Guys arrived two days later. In the violence that ensued they savagely beat up a policeman and Jacob had to intervene by reading the Riot Act.

The mayor persuaded the town council to employ an extra nine constables, plus a new superintendent. He was John Henry Law and one of the first changes he made was to arm his men with cutlasses. Perhaps this and the cold frosty weather were the reason why November 5, 1864, was, in comparison to other years, a fairly quiet night.

A brave policeman faces the rioters. Picture from ‘The Guildford Guy Riots’ by Gavin Morgan.

The following year was also quiet. Was this the end of the Guildford Guy’s reign of terror? Nearly, but not quite. On Boxing Day about 20 Guys entered the town and attacked PC Stent. He ran up the High Street but they gave chase, knocked him to the ground and savagely beat him with sticks and clubs. More officers arrived and further scuffles took place.

Four Guy’s were arrested and later appeared at Kingston Assizes. Two were found guilty of rioting and causing bodily harm and each was sentenced to three months’ hard labour. After that there were no more riots in Guildford.

But who were the Guys? The four who were arrested were all in their twenties. Two gave their professions as painters; one was a cooper and the other a coachsmith’s labourer.

In the excellent book, ‘The Guildford Guy Riots’ (Northside Books, 1992), the author, Gavin Morgan, suggests that the activities of the Guildford Guys was largely a rural tradition and as society became more disciplined, support for it faded.

Similar activities took place in other towns across Southern England, notably Lewes in East Sussex. By making the ‘celebrations’ official the authorities there were able to put a stop to the violence. They are continued in a peaceful, although often boisterous nature, to this day.

The story of the Guildford Guy Riots will be covered in David Rose and Martin Giles’ guided history walk and talk starting at the Angel Hotel this Sunday, November 6, at 2.30pm.

Recent Comments