Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Spare a Thought Today for Guildford’s Own Great Escape Airman

Published on: 24 Mar, 2019

Updated on: 26 Mar, 2019

Alec Bristow in 1940.

Guildford today should recall the loss of one of its great unsung World War 2 heroes, former Squadron-Leader Alec Bristow, Mosquito pilot, and a lucky survivor of the legendary Stalag Luft 111 Great Escape that took place 75 years ago today (March 24, 2019). 76 officers escaped. Four were captured at the time. Of the 72 who got away, 50 were murdered on Hitler’s direct order. Only three made “home runs”…

By Joanna Bristow-Watkins (Alec Bristow’s daughter)

My father was born in Epsom, October 20, 1916, in what appears to have been a poorhouse. His mother was unmarried and his birth certificate shows no father’s name. He grew up at Camelot, Old Farm Road, Guildford with his aunt and uncle William and Matilda Bristow with their seven children.

They treated him kindly, he told us, as if he was one of their own. William Bristow worked for the Surrey Times newspaper 1890-1930, ending up as the Editor.

The Bristow boys, Alec Bristow (top left) with his half brothers, Tim, Don, Doug, Pete.

Alec was educated at Charlotteville, Stoke Hill, Stoke, Bellfields and Guildford Junior Technical School and was also a chorister at Holy Trinity when it was the pro-cathedral in the 1930s.

June 8 1941 – Alec and Joan Bristow on their wedding day.

He was very bright, having amazing skills at mental arithmetic, and chose the Technical School to be with his half-brothers. In 1938, he joined Holes Dairy in Brighton, where he met Joan Hazeldean and they married June 8, 1941. They had three daughters, Angela, May 18, 1946, Fiona, March 23, 1957, Joanna, August 25, 1960.

Alec had joined the RAF Voluntary Reserve in January 1939, and was mobilised at outbreak of war. He was commissioned as a Flight Lieutenant pilot with Bomber Command, initially on Blenheims, then on Mosquitoes. Three of his half-brothers served with him in the RAF. On return from successful Mosquito missions, he would often do a victory roll over Guildford to let his family know that he was OK.

In September 1942, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for the Oslo raid on Gestapo HQ. This was one of the first official missions by the new Mosquito, a super-light twin-engine fighter-bomber with a reinforced wood frame. With only a pilot and navigator, the 300mph Mosquito was at its most effective when flown at exceptionally low level.

But on October 6, 1942, Alec’s Mosquito from 105 Squadron flew into a flock of curlews, smashing the windscreen, knocking him unconscious. Unable to see after he came to, they had to land back home without radio contact, his navigator, Flt-Lt Bernie Marshall kicking him left and right to guide his steering. After four attempts, they made a perfect landing.

The wooden framed De Havilland Mosquito.

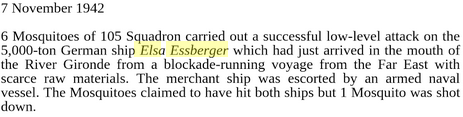

On November 7, 1942 in Mosquito DK328, on a mission to attack merchant ship Elsa Essberger, near Bordeaux. Alec and Bernie were forced to ditch the plane in the sea and waded ashore.

Bomber Command War Diary entry for the Elsa Essberger raid.

Having flown in a then all-new Mosquito, they were repeatedly interrogated by the Gestapo, but gave only their name, rank and serial number. Being RAF officers, they were lucky to be sent to the specialist PoW Dulag Luft and Stalag Luft camps staffed by Luftwaffe fliers.

Eventually, on March 30, 1943 Alec arrived at North Camp Stalag Luft III (SL3), site of the The Great Escape, portrayed in the 1963 Hollywood blockbuster, rather a fantasy starring Steve McQueen, Donald Pleasence, Richard Attenborough etc.

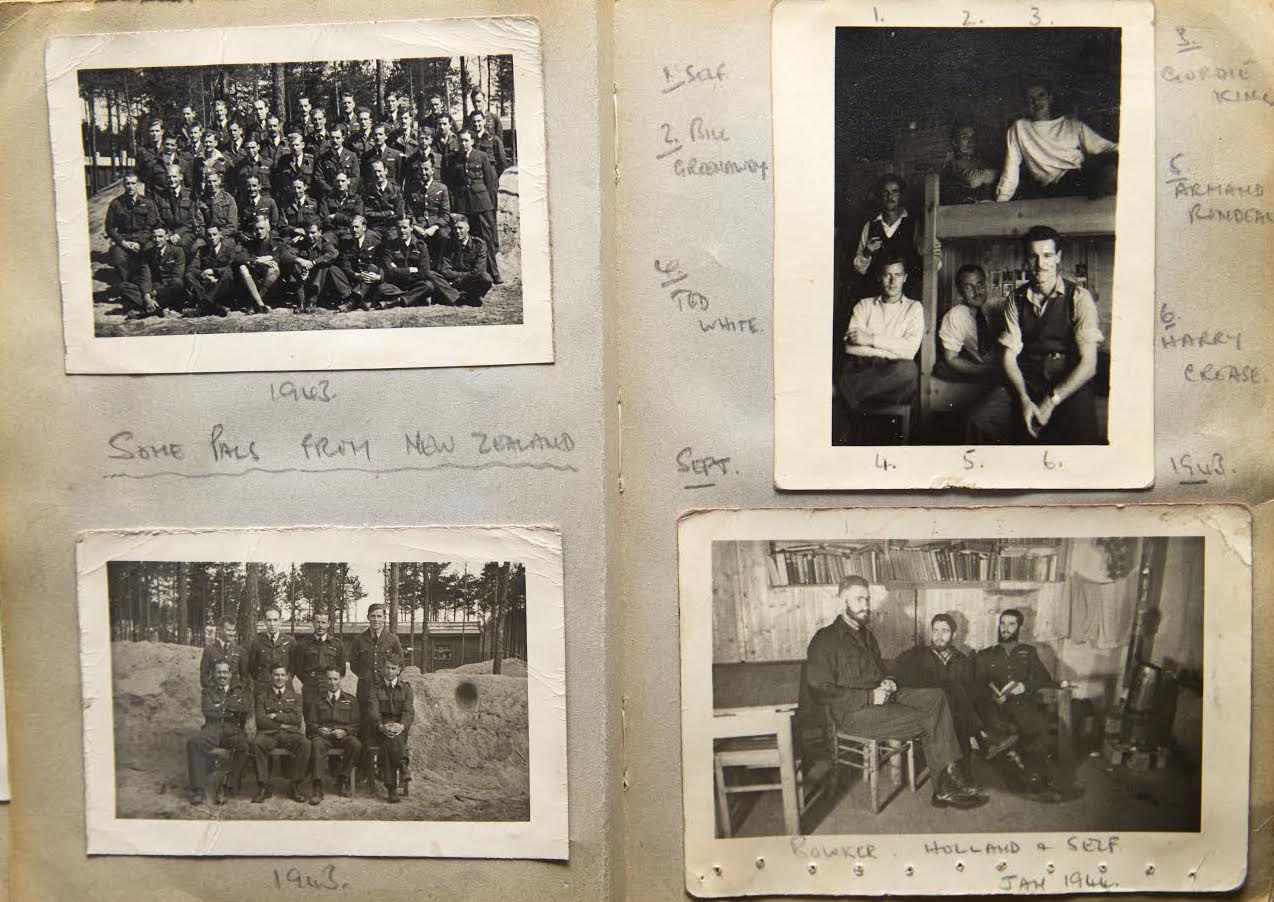

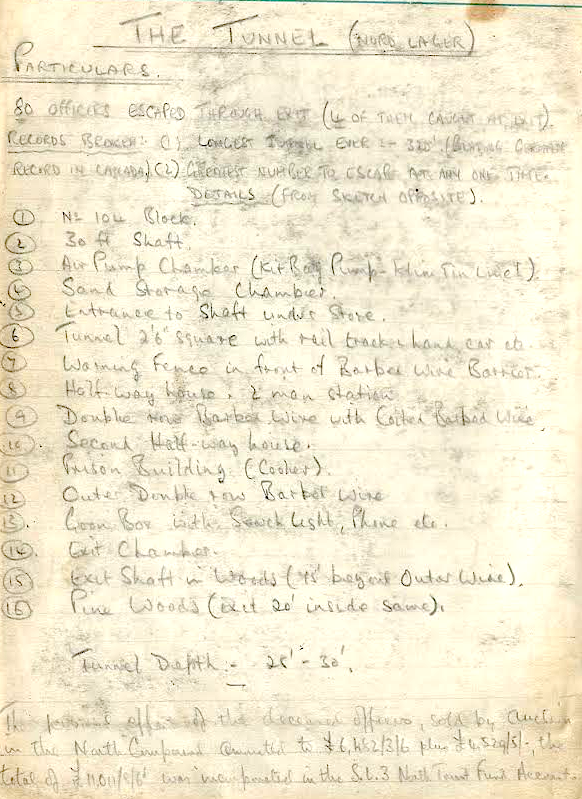

A page of Alec Bristow’s diary when a POW in Stalag Luft III

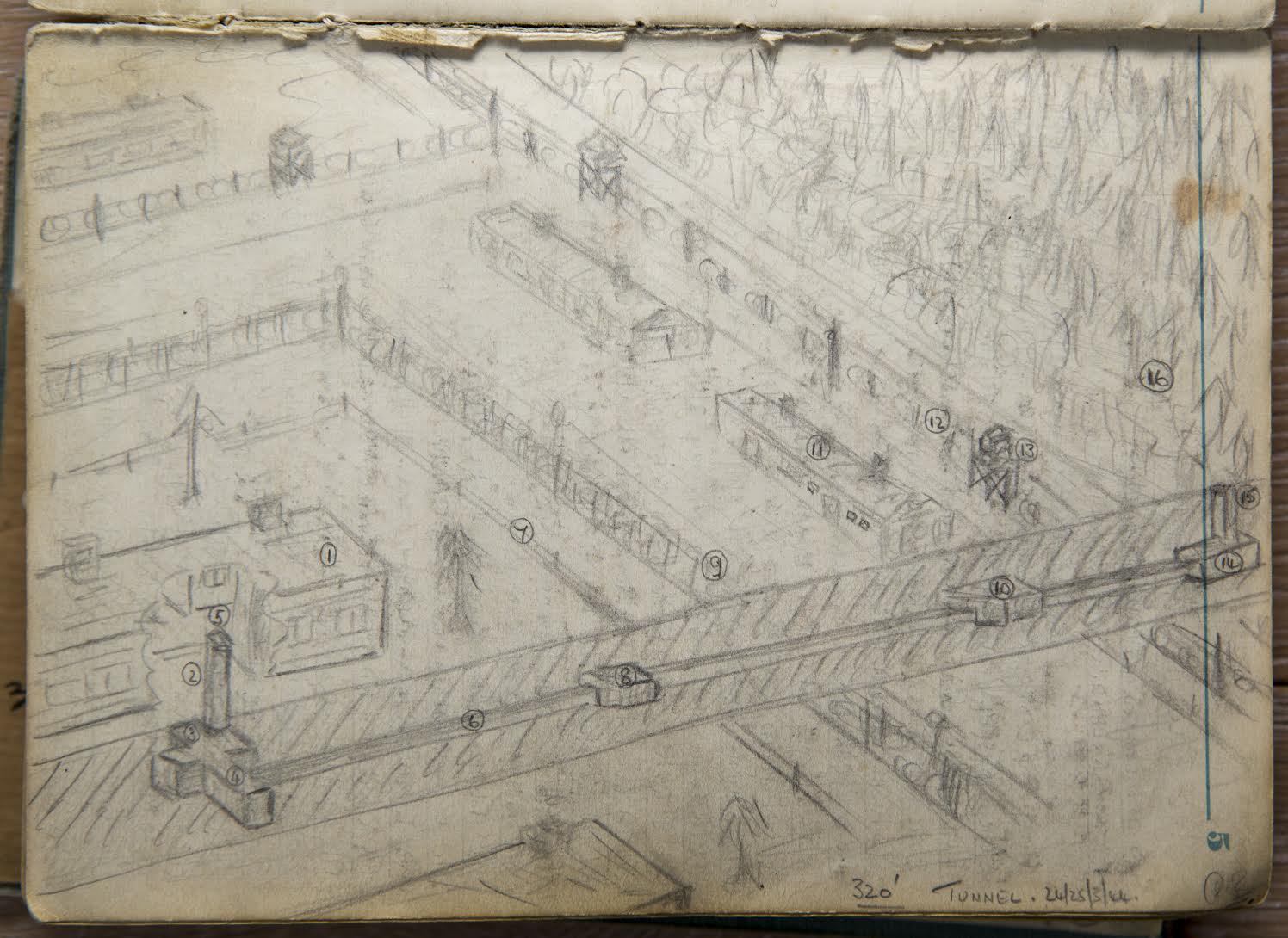

Alec found the X Committee (escape planners, led by Roger Bushell) in full swing with the three tunnels Tom, Dick and Harry already underway. Alec promptly volunteered to help with shoring up the tunnel, a necessity in unstable sandy soil. That meant regular looting of bunk slats and bits of their wooden huts. Tunnel diggers also risked being suffocated by soil collapses and men did have to be rescued.

Equipment was begged, stolen, and engineered, enabling the tunnel to be rigged with fresh-air bellows and electricity. Rails were installed so wooden carts could move men and soil along. Escape equipment was made, compasses (from melted razor blades and Bakelite records), civilian and foreign worker clothes, maps collated etc.

Page from Alec Bristow’s wartime diary showing Stalag Luft III with details relating to the Great Escape. Image Steve Reigate.

Diary page showing key to above. Image Steve Reigate.

Other PoWs distributed the yellow sand unobtrusively throughout the dark camp soil and others acted as lookouts to warn of guards approaching. The final tunnel was a staggering 30ft deep and 320ft long, going under the “cooler” (solitary confinement hut) to come out well past the boundary wires into a shielded wooded area. The elaborate and ambitious escape plan was to get at least 200 men out. After 15 months of preparation, the tunnel was ready but it was actually 30ft short of the woods

They drew lots: the first 100 were allocated to those most likely to be successful, German-speakers, or foreign-language ones, prioritised with better forged documents, maps, civilian clothes etc. The second 100 included Alec, number 151. But without properly forged documents they would have to avoid public transport, lay low by day and travel by night in freezing weather.

When the tunnel came up short of the woods, right by a German observation tower, the first escaper rigged up a rope to signal the others when it was safe to emerge. In the middle of the escape, there was a power-cut and the tunnel was temporarily plunged into darkness. Then a guard noticed the trail to the woods. The next would-be escapers heard gunfire and hurriedly backed up, fearing shots might be fired up the tunnel.

The camp commandant, Oberst von Lindeiner, a highly decorated First World War soldier, was court-martialled and stricter rules were enforced. He had warned the RAF officers that severe punishments for escape were being discussed. He was reported as horrified by the 50 executions and was said to have rather have shot himself if he’d been consulted.

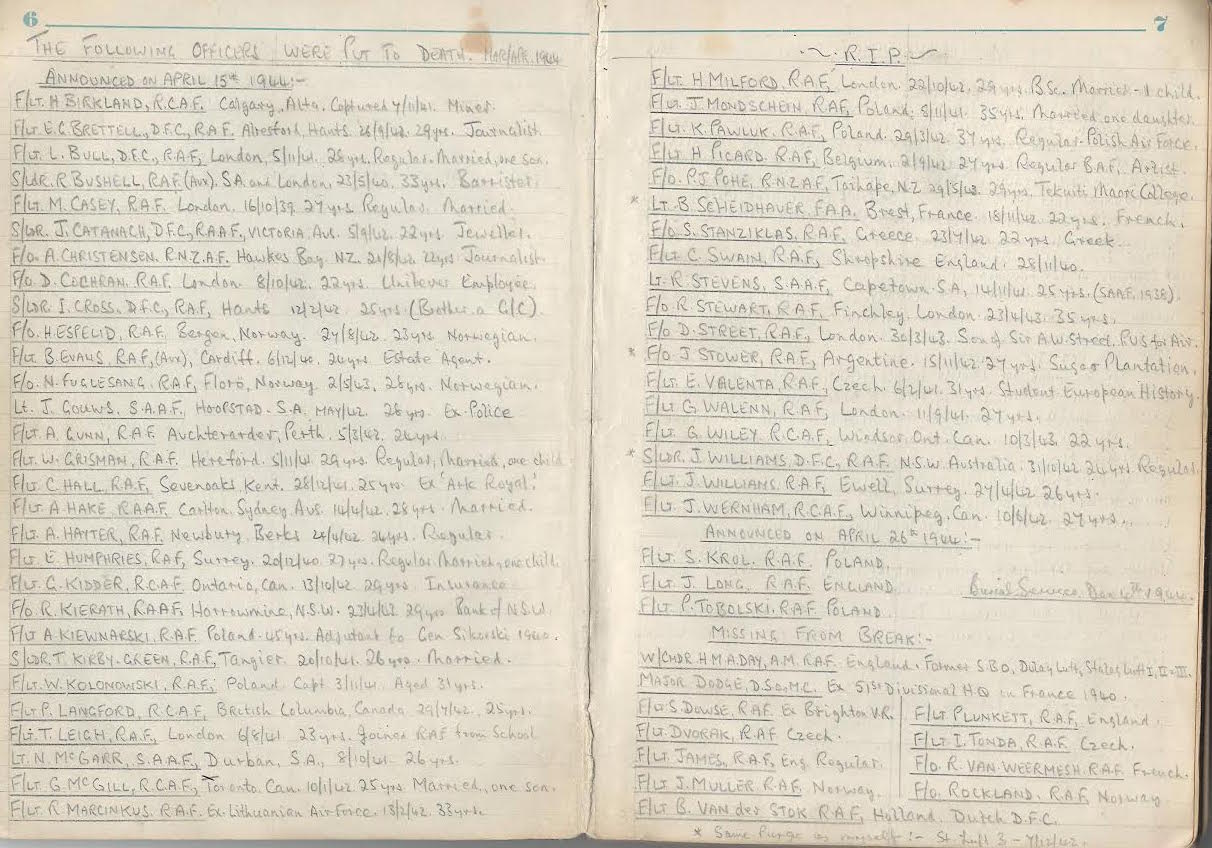

Alec Bristow’s list of the 50 POWs executed after Great Escape.

A very sad end to this brave attempt; from which only three made it back to neutral countries. In his wartime diary, Alec wrote a list of those put to death, including Roger Bushell, with details of the home town, date of capture, age and profession, with poignant asterisks against those who had been fellow SL3 POWS since his “purge” (camp intake) December 7. 1942.

Alec remained at SL3 until the enforced march across Germany in 1945. The diary gives much detail on this gruelling trek (starting January 28) which he described as the worst time of his life for sheer cold, hunger, thirst and utter exhaustion. He arrived back in England on May 7, 1945, having spent exactly 2½ years to the day as a POW Kriegie (shortened slang for Kriegsgefangener, German for POW).

He was demobbed after the war (going to Cow and Gate Dairy, Guildford) but re-joined RAF April 1947, as a flying instructor on heavy bombers. Based at Little Rissington. As well as Mosquitos, he flew Lancasters, Wellingtons and Blenheims during his RAF service. The Air Force Cross was awarded for post-war services. He left the RAC as a squadron-leader in 1958. Alec was a senior pilot instructor for BOAC then BA on 707s and VC10s until 1980.

Bristow Travel Woking

He opened Alec Bristow Travel in Chertsey in 1963. This subsequently grew to five shops including branches at Walton-on-Thames, Woking (two) and Esher. By 1988, the chain employed 50 and enjoyed annual turnover of about £8 million.

Alec Bristow Travel had a poster and cinema advertising campaign around north-west surrey showing a hot-air balloon with the slogan “The Great Escape Begins at Alec Bristow Travel”. Few people knew the relevance.

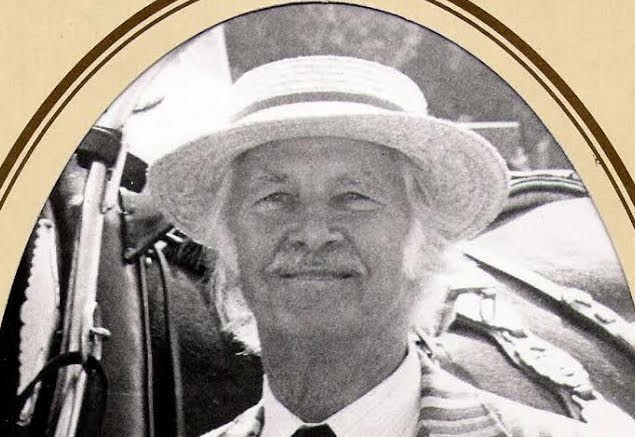

Alec Bristow in later life.

Our dear father Alec died peacefully in his sleep on October 18, 1990, two days before his 74th birthday. Fiona Stephenson and I took over as joint managing directors and the company limped along through the Gulf War recession until we sold out on January 31, 1995.

Author and Alec’s daughter Joanna with her sister Fiona & Alec’s grandaughter Scarlett (centre) holding the war diary. Photo Steve Reigate

We have also made a one-hour programme with Graham Laycock of Brooklands Radio which will be aired twice on Sunday (12 noon and 7pm) and available afterwards as a podcast. See https://www.brooklandsradio.co.uk/schedule.html for the programming details.

Anyone related to, or with information about, the Guildford Bristow family and/or Stalag Luft III, please email Joanna at jo@thegreatescape.com

Responses to Spare a Thought Today for Guildford’s Own Great Escape Airman

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.

Recent Articles

- Burglar Jailed Thanks To Quick Action of Ash Resident

- Highways Bulletin for December

- Birdwatcher’s Diary No.318 Some Pre-Christmas Rambles

- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to All Our Contributors and Readers!

- More Units Added to Solums’s Station Redevelopment

- Vehicle Stop on Epsom Road Leads to Prolific Drug Gang Being Put Behind Bars

- Local Political Leaders Respond to Publication of the English Devolution White Paper

- Flashback: Guildford All Lit Up For Christmas – Then And Now

- City Earn Themselves a Three Point Christmas Present

- Mayor’s Diary: December 23 – January 4

Recent Comments

- Jim Allen on Two Unitary Authorities, One Elected Mayor – Most Likely Devolution Outcome for Surrey

- Mike Smith on Two Unitary Authorities, One Elected Mayor – Most Likely Devolution Outcome for Surrey

- Angela Richardson on Two Unitary Authorities, One Elected Mayor – Most Likely Devolution Outcome for Surrey

- Frank Emery on Two Unitary Authorities, One Elected Mayor – Most Likely Devolution Outcome for Surrey

- Paul Kennedy on Two Unitary Authorities, One Elected Mayor – Most Likely Devolution Outcome for Surrey

- Alan Judge on Dumped E-bike Provokes Questions

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Ben Paton

March 24, 2019 at 2:47 pm

What an heroic, inspiring tale and a marvellous tribute to a great man.

My uncle flew Mosquitoes and later Hurricanes for 600 Squadron. Miraculously he survived the war.

George Sandy

March 25, 2019 at 9:09 am

Fascinating account. What a great man. His family must be very proud of him.

I remember the travel agents, we used them several times.

Mary Bedforth

March 25, 2019 at 12:52 pm

Thank you. His family must be very proud of such an amazing man. The country owed him a great debt.

Cllr James Walsh

March 27, 2019 at 1:19 pm

What a great story and a man I would have like to have met. Great too to read about his link to my ward – a piece of local history that should never be forgotten.

Thanks to Joanna Bristow-Watkins for writing this article.

Scott Clare

April 12, 2019 at 2:01 pm

Thanks for such a wonderful article. My late Uncle, F/O Earl Clare was also an inmate of “SL3” from Jan. ’44 until being Liberated after the “Long March”, probably April ’45.

Keep up the great work in sharing and preserving the memories of those brave men. Sadly, there are so few left.

My own father (died in 1996) was also a PoW. He was a medical officer with the Canadian Army and caught at Dieppe, France, Aug. 19, 1942.

He spent most of his time as a PoW in Stalag VIII-B (later named Stalag-344) in South Poland. He was also part of the “Long March” and was liberated in Follingsbostel, Germany on Easter Monday, April 1945, by elements of the British Army. See: http://ww2today.com/16-april-1945-the-first-pow-camp-liberated-fallingbostel.