Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Birdwatcher’s Diary No.120

Published on: 2 Oct, 2016

Updated on: 2 Oct, 2016

By Malcolm Fincham

As September drew to a close and the autumn equinox passed by, a few more local sighting of wheatears came my way.

Once again it was at a farm in Blackheath, on the outskirts of Guildford, where I had seen one just a week or so previously.

This time there were two present. I also picked out a slightly smaller bird close by as it repeatedly dipped down into a horse paddock then returned back to a fence post.

”The habits of a stonechat ?” was my first thought, as it returned to the same post it had just left. However, on closer inspection, I noticed it had a white supercilium. I realised it was in fact a whinchat.

A continued spell of mainly dry and mild weather gave me the opportunity to photograph some of our late-summer butterflies, still out on the wing.

These included numerous red admirals competing with bees for pollen as they settled on flowering ivy.

Several small coppers could also still be seen, one giving a view of its under-wing.

As well as plenty of speckled wood butterflies, often seen spiralling into the air to chase each other and defend their territories.

Various colourful dragonflies were also still displaying.

Getting pictures of what I believe to be common darter and southern migrant hawker.

I also received a request from a small posse of pals to revisit Papercourt watermeadows on what turned out to be a successful mission to see the barn owl I photographed there a few weeks ago.

I even managed to ‘snatch’ a few more shots of it as it hunted over the long grass.

The Sheppy Crossing. It is the only road access to the island aloingside the older Kingsferry Bridge.

As daylight hours drew shorter, I was invited on a trip to the Isle of Sheppey. Always interested in a new venture and once again thanks to the inspirations of Dougal, with his passion of seeing critters to add to his own list of new sightings.

Sheppey, as mentioned in a few of my early reports, is the place I visit annually to view the variety of birds of prey that winter there. This time it was in the hope of getting photos of a few creatures of a non-indigenous kind.

The marsh frog was first introduced to Walland Marsh, Kent in 1935. It is said, by the wife of E.P. Smith, MP for Ashford, who wanted to surprise him with some edible French frogs to put in the garden. Unfortunately French frogs were unavailable so she bought some large Hungarian frogs instead. These promptly escaped from their garden in Stone-in-Oxney and spread across the ditches of the marsh with great success: colonising the entire Romney Marsh area by the 1960s.

This frog is now found in several areas of Kent and East Sussex. It is by far the most successful introduction, thought to occupy an ecological niche; they choose breeding sites such as dykes and ditches not generally chosen by our native amphibians.

However, the marsh frog is a voracious predator and further spread of this species in the UK is inadvisable due to unknown impact on native herpetofauna, and illegal under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. Other introductions are known to exist, including colonies in south-west and west London. It is possible to determine the main source of origin of marsh frogs as there is a subtle difference in the frequency of their calls as longitude changes from east to west.

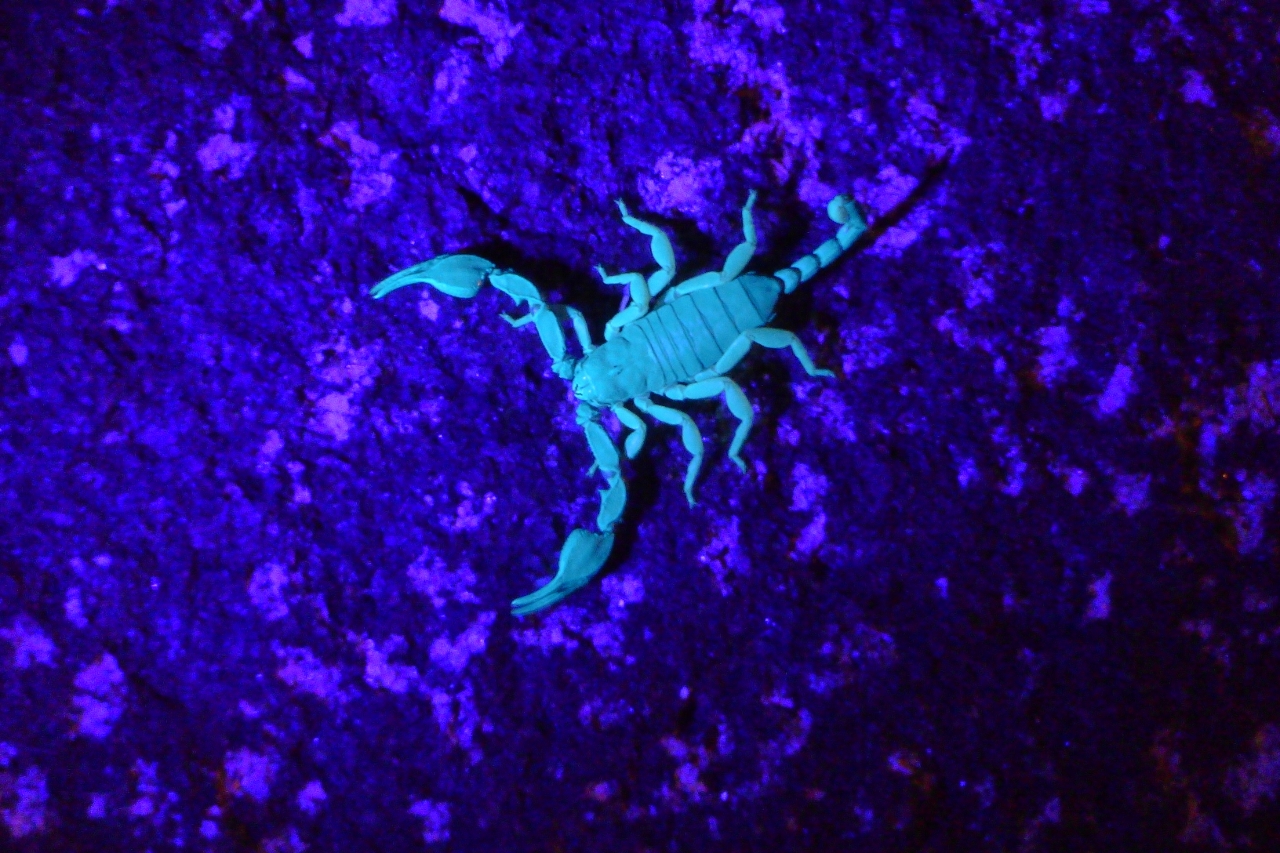

The main reason for our visit there was to try to get a sighting of a critter that had stowed away on cargo ships, in the crevices of rocks.

Yellow-tailed scorpions have, over the years, set up colonies around the walls of the dockyard in Sheerness. This population was the first recorded in the UK way back in the 1860s.

It is believed the Sheerness scorpions arrived in cargoes of Italian masonry. The majority are thought to have arrived during the Georgian era and settled at the port’s dockyard. In recent years they have multiplied vigorously. There are now reckoned to be between 10,000 and 15,000 ‘yellow-tails’ living in crevices in the dockyard walls.

During the day these scorpions can be almost impossible to find as they hide in the smallest of gaps in brickwork.

During the day these scorpions can be almost impossible to find as they hide themselves away in the smallest of gaps They have occasionally been found at several coastal towns across the south of England over the years, but the best known and most successful site is on the Isle of Sheppey at the dock-land town walls of Sheerness.

The yellow-tailed scorpion has large pincers for its size and a small stinging tail. This tail can only deliver a very mild sting to a human. The yellow-tailed scorpion is usually very reluctant to use its sting and the effect is said to be comparable to that of a mild bee sting at worse and usually poses no threat to healthy adults, although I had no desire to test these claims. There are no records of anyone that has experienced any signs of aggressive or defensive behaviour from any of them.

As you can see from the pictures I took, these guys are really quite cute! The yellow-tailed scorpion grows to a couple of inches in length and is dark chocolate brown with a yellow-tipped tail.

In fact, for most of their lives, they do absolutely nothing. They live in crevices without moving until a woodlouse or spider ambles by. They then pounce, and devour the pitiable passer-by. Thanks to an incredibly low metabolic rate, yellow-tails can live on only four or five such catches a year. Essentially, they are active for about 10 minutes every 12 months.

Occasionally, a few scorpions manage to travel to other sites and set up independent colonies, but none seem to survive for long periods. Only the Sheerness scorpions have thrived.

This scorpion colony is still the most famous one in the country, having tolerated our UK climate there for over 150 years, but there are now said to be populations of European yellow-tailed scorpions in and around the London area as well as north Devon that have continued to survive.

Responses to Birdwatcher’s Diary No.120

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.

Click on cartoon for Dragon story: Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

Recent Articles

- Final Phase of Deepcut Redevelopment Approved

- GuilFest Returns to Stoke Park with Global Names and Local Soul

- Exercise May Aid Body’s Immune Response Against Cancer, Pilot Study Finds

- Letter: How Surveys of Public Opinion Should Be Organised

- Catapult Attacks, Shoplifting and Graffiti – the ASB Problem That Ash Is Facing

- A281 Closure Expected to Continue

- Guildford’s Green Day Shows Commitment to Net Zero by 2030 Remains

- Letter: We Should All Have a Say in How Our Local Government Is Reorganised

- Dragon Review: Madam Butterfly – Grange Park Opera

- Letter: PIP Claimants Under-claim

Recent Comments

- Roger Kendall on Catapult Attacks, Shoplifting and Graffiti – the ASB Problem That Ash Is Facing

- Anthony Williams on A281 Closure Expected to Continue

- Jules Cranwell on Flashback: Council Report Accepts Juneja Case Has Caused ‘Reputational Damage’

- Tony Harrison on Letter: Reduced Speed Limits Will Save Lives

- Tony Harrison on A281 Closure Expected to Continue

- Helena Townsend on Letter: Not All PIP Claimants Need It

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Harry Eve

October 3, 2016 at 12:45 pm

I have had a look at the Sheerness wall a couple of times in daylight and while I failed to spot a scorpion – so thank you for these excellent photos.

There are plenty of other interesting creatures on the wall too – including the magnificent Segestria florentina, a large spider that hides in the crevices and leaps out to catch woodlice (or fingers of the unwary!) when its “trip wires” are triggered.

Passers-by must wonder why they see people staring at the wall and, apparently, photographing intricate details of the brickwork.

Regarding the dragonflies, it is only the superb detail of Malcolm’s photos in flight that enable me to suggest that the southern migrant hawker is actually a migrant hawker.

The most obvious difference is the marking on the side of the thorax (see website of the British Dragonfly Society http://www.british-dragonflies.org.uk/species/southern-migrant-hawker).

Both species have an interesting history of arrival in the UK with the “southern” being the more recent.

The migrant hawker was once a rarity here.

The likely reason for their arrival seems to be climate change.

Another local indicator of the opposite effect of climate change is, I think, the loss (in fairly recent years) of the white-faced darter from Thursley.

Malcolm: what settings do you use for those dragonfly-in-flight photos?

Paul Hart

October 4, 2016 at 7:27 pm

One needs to go no further than the RHS gardens at Wisley to see and hear marsh frogs.

In breeding season they can be found in the waterlily canal in front of the laboratory by the entrance, in the ditch to the right of the path to the glasshouses, and in the reservoir in front of the glasshouses. They are incredibly loud when courting.

Malcolm Fincham

October 9, 2016 at 12:28 am

I would like to thank Paul Hart and Harry Eve for the additional information they have provided. All of which I was unaware of.

Especially interesting I thought were details about the Segestria florentina spider.

Having since looked closely and cropped the picture above, entitled ‘Can you spot the scorpion’ I have noticed there is in fact a spider in a crevice in the brickwork to the right of the scorpion. Could this be the said critter mentioned by Harry Eve?

In answer to the question about ‘inflight’ photos. Taking photos of fast moving objects, I set a shutter speed of at least, 1/1600 and set ISO on auto.

It is best achieved on bright, sunny days. I am fortunate to have an F2.8 lens, which I often use for such shots. This lets in more light and a results in a less ‘grainy’ end product.

James Sellen

October 9, 2016 at 11:31 pm

Excellent photos of the hawker and common darter – not easy to photograph. Fascinating information concerning the yellow-tailed scorpions.