Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Eighty Years Ago Britain Declared War on Germany And Evacuees Poured Into Guildford

Published on: 3 Sep, 2019

Updated on: 3 Sep, 2019

By David Rose

Eighty years ago on September 3, 1939, Britain declared war on Germany.

It was a Sunday morning and at 11.15am Britain’s prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, broadcast to the nation on the wireless the famous words: “This morning the British ambassador in Berlin handed the German government a final note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

Britain’s home front was soon to face prolonged rationing, the blackout, air raids, people having to carry identity cards and gas masks, and over five years of total war.

In Guildford the town received the news in the time-honoured British tradition of calmness. The Surrey Advertiser of September 8, 1939, wrote: “There were no demonstrations of any kind, rather than an emotional display, was abroad to herald the new epoch in modern history.”

It added that most people stayed at home to hear Chamberlain’s broadcast, while in some local churches “wireless sets had been installed for the occasion”.

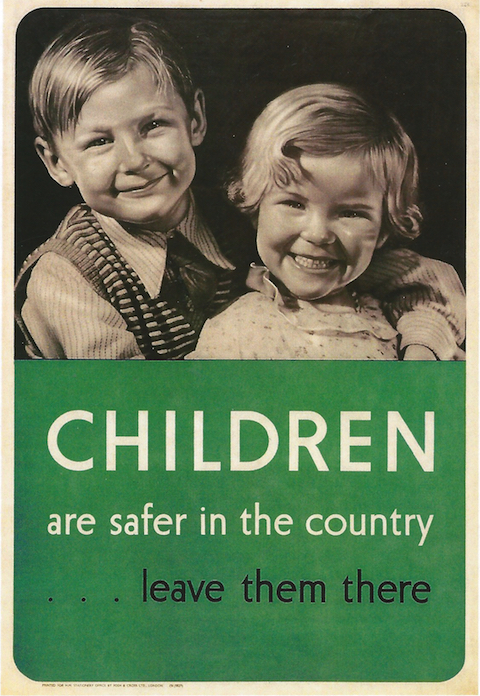

Friday, September 1, saw the start of Operation Pied Piper, the evacuation of Britain’s urban areas at the start of the Second World War. It has been said that it was the biggest and most concentrated mass movement of people in Britain’s history.

Nearly three million people were transported from towns and cities perceived to be danger from enemy aircraft to places deemed safer in the countryside and surrounding towns. Most went by train, others by motor-coaches, buses or private cars.

Preparations for accommodating children, some with their mothers, and whole schools with their teachers had been made earlier in the year. It is believed that on that Friday 259 adults and 2,109 children were received in Guildford.

A total of 1,423 were billeted in Guildford borough with 945 in the nearby district.

On the Saturday another 738 adults and 1,161 children arrived, of whom 970 were billeted in Guildford borough and 929 in the rural area.

On the Sunday 51 adults and 111 children came, the borough taking 128 and the rural area 34. London Transport buses bought a total of 115 expectant mothers to the area. The evacuation in Guildford was completed by the Sunday afternoon.

In the main, evacuees to the Guildford area came from London boroughs south of the River Thames.

In total, 1.5 million people were evacuated from London to the provincial towns. Banners and signs guided the evacuees through embarkation points. All children wore a paper label. Although obviously chaotic, with some journeys taking many hours, there were remarkably, no casualties or accidents.

The Surrey Advertiser reported: “To deal with difficulties connecting with the billeting, a number of headmasters of the elementary schools have assisted the town clerk’s department.”

The state paid those who took in people 10 shillings and sixpence a week for the first child and eight shillings and sixpence for each additional child. In an evacuated home where a mother and her children were living, the householder was only expected to provide lodgings and and was paid five shillings per adult and three shillings per child. The mother had to buy and cook all her own food.

There were, not surprisingly, problems, one being a change of diet was upsetting some children. The Surrey Advertiser noted: “Accustomed to fish and chips, tinned salmon and other similar commodities, the introduction of a plentiful supply of fresh vegetables has resulted in many of the children having trouble with boils. More nursing help is needed to cope with the many cases.

“The general opinion is that the billeting of mothers and young children is not a success. The standards of life seem utterly opposed to each other and a number of distressing stories could be told.”

Differences in religious backgrounds also created problems, as did differences between a rural life and an urban one left behind.

Air-raid sirens were first sounded over Guildford on September 6. It was a preliminary warning and was reported in the press as: “Such a warning is in the nature of a stand-by order to ARP workers. There are 50 per cent of the ARP staff always on duty now, and by 8am, almost 100 per cent of the borough service was ‘ready to go’.

“ARP personnel who had gone off duty were called away from their breakfast. The kippers cooled on more than one plate when the off-duty men hurried to their posts. By 8am there were 80 men standing at Stoke Park ready for emergency, men of rescue parties, decontamination squads and road repair gangs.”

German air raids did not come until the following year with Guildford’s first high explosive bomb falling in The Mount cemetery on August 16, 1940.

Back to the autumn of 1939, and with no air raids on urban areas, children feeling homesick and the cost of travel weekly for weekly visits by parents, it was not long before many children went back to their homes.

This story contains extracts and some images from Guildford The War Years 1939-45, by Graham Collyer and David Rose, published by Breedon Books in 1999.

David Rose will be one of the guides adding wartime history details on a free walk on Sunday, September 15, hosted by the National Trust’s River Wey and Godalming Navigations. Part of Guildford Walkfest 2019, meet at Dapdune Wharf, Wharf Road, Guildford GU1 4RR at 2pm. Click here for more details on the Guildford Walkfest website.

Responses to Eighty Years Ago Britain Declared War on Germany And Evacuees Poured Into Guildford

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.Recent Articles

- Guildford Museum Shares Jekyll’s Boots with British Library for New Exhibition

- Stoke Park Paddling Pool Stays Closed After Tests Show Contamination

- Freiburg Artists Coming to Guildford

- Highways Bulletin May 26 – Godstone Sinkhole Update

- Mayor’s Diary: May 23 – June 8

- Letter: If GBC Wishes To Be Nature-friendly, Stop Spraying Weedkiller

- Conservation Groups Say Government Policies Are a Threat To Wildlife

- Have You Seen Alexander?

- Millions of Taxpayer Money Recovered from Railway Fare Dodgers

- Notice: Have a Blooming Picnic – June 7

Recent Comments

- M Durant on Millions of Taxpayer Money Recovered from Railway Fare Dodgers

- Jim Allen on Letter: If GBC Wishes To Be Nature-friendly, Stop Spraying Weedkiller

- John Lomas on Stoke Mill To Be a Pub If Plans Are Approved by Borough Council

- Rebecca Brion on Letter: Is This the Ugliest Building in Guildford?

- Brian Quinn on Letter: This CIL Injustice Needs To Stop

- Jacques Pillay on Remembering the Guildford Pub Bombings on the 50th Anniversary

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

John Lomas

September 5, 2019 at 1:36 pm

I was born in 1942, so obviously I don’t remember this, but I knew my parents had evacuees and military “billetees” during some of the war.

Looking at the 1939 register I can see the names of two brothers 10 and 12 years of age with my parents and one hidden record (Any visible record discloses that that person is now deceased)

The 1939 register is available at Findmypast.co.uk

So I could name two of those evacuees if David Rose doesn’t think it too intrusive.

Jeanette Fisher

November 24, 2020 at 7:01 am

My mum, aunt and uncle were moved to Shalford after initially being evacuated to Shoreham. My mum and aunt stayed, I believe, with two spinster sisters on the green whilst my uncle was taken in by Sir Edward and Lady Margaret Dunbar at Beech House and he clearly remembers Sir Edward leaving every morning on his bicycle to ride to Guildford station where he caught the train to his office in London.

My mum and aunt attended the local village school whilst my uncle attended lessons in the village hall.