Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

How The Spanish Flu Pandemic In 1918 Was Reported In Surrey

Published on: 18 May, 2020

Updated on: 24 May, 2020

By David Rose

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-20 has been said to have infected about 500 million people worldwide (about one-third of the World’s population), killing an estimated 20 million to 50 million victims.

The first known case is reputed to have been reported at the military Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 11, 1918. It has been suggested that it spread among American troops, many of whom brought it with them when they came to fight with the Allies on the Western Front. However, other theories suggest it may have been spreading around the world before then.

It is said that it took its name from Spain, a country that was seriously affected by the disease. Even Spain’s king, Alfonso XIII, was reported to have been seriously ill with the flu.

Spain was a neutral country during the First World War with no censorship restrictions. News of the pandemic there was widely reported, including King Alfonso’s illness and recovery.

In many of the countries engaged in the war, reporting of the severity of the pandemic was concealed, least moral would dip – especially in Britain.

Soldiers partake in their morning wash at Witley Camp. No social distancing!

Of course Surrey did not escape Spanish flu. The numerous military camps in the county housing thousands of troops most likely spread the disease as they mixed with local people in local towns and villages while in their spare time and also with the civilians who were employed in the camps.

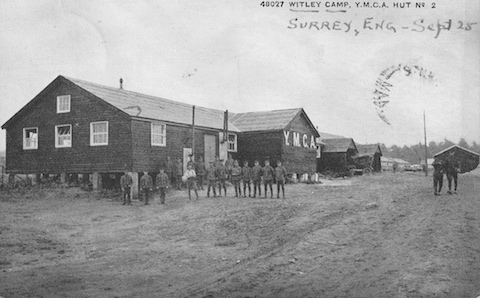

One of the YMCA recreation huts at Witley Camp where soldiers and YMCA staff mixed freely.

Locally these included Witley Camp that covered a huge area either side of the Portsmouth road (now the A3) on Witley and Rodborough Commons. Thousands of Canadians were stationed while training for warfare.

There was a further camp over the border into Hamshire at Bramshott; and more camps in and around Pirbright and towards Frimley, in the Epsom areas, and Inkerman Barracks, Woking, where troops from South Africa were stationed.

A report in the Surrey Advertiser of October 26, 1918, gives an insight into the effects of the pandemic and makes a reference to the situation at local military camps.

Under the heading ‘A WIDESPREAD EPIDEMIC’ it noted: “Surrey has not escaped the prevailing epidemic of influenza, and from all parts of the county come reports of schools closed in consequence of the scourge, and of numbers of victims among the people.

“But, so far as we have been able to gather, there have been comparatively few deaths among the civil population as a result of the epidemic, and if people who are threatened take prompt care of themselves there is no reason for undue alarm.”

Inkerman Barracks, Woking.

The report then turns to the military, making the point: “In the camps it is a different matter. The influenza has claimed victims by hundreds, and unfortunately, a goodly number of cases have had a fatal termination. The military authorities are doing all that is possible with wholly inadequate medical staffs to deal with the situation.”

The story then focuses on the situation in schools and notes that: “It has been deemed advisable to prevent the children from assembling and spreading infection.”

The report listed the following towns that had taken action: Guildford, Chobham, Byfleet, Bisley, Leatherhead, Kingston, Malden, Chessington and Long Ditton.

While adding that “elementary schools in Woking have been closed for a week or two”.

Shalford School at about the time of the First World War.

The Spanish flu typically affected younger people more than the elderly. There is evidence to suggest that older people may have had partial protection caused by exposure to the Russian flu pandemic of 1889-1890.

The Surrey Advertiser’s report also stated: “Doctors everywhere are extremely hard worked. One at Kingston stated that he had visited no fewer then sixty patients; another at Woking said: ‘From early morning till late at night I have done nothing but rush from one “flu” patient to another’.

“At Bookham the only doctor was himself a victim, and at Leatherhead two other medical men were temporarily put hors de combat by the complaint.

“Dr Brind, at Chertsey Rural Council on Tuesday, said a good many people who had the ‘snivels’ thought they had influenza, but fortunately for them it was not that complaint.”

The Surrey History Centre’s excellent website Surrey In The Great War – A County Remembers gives further details about the Spanish flu pandemic in the county.

It too notes that it bred in the overcrowded and insanitary trenches and army camps and first struck in Surrey in the summer of 1918.

Quoting from local newspaper stories throughout Surrey (in normal times available on microfilm at the Surrey History Centre in Woking), it includes: “Schools were closed, often for weeks at a time,” and the Surrey Advertiser of December 4, 1918, advised that “Guildford schools were to be closed to the end of the year”.

There was no miracle cure for Spanish flu and a vaccine was never developed, but local newspapers published details of how people might avoid infection or how it could be contained.

Again, quoting from Surrey In The Great War – A County Remembers: “The advice of the Local Government Board, reported in the Epsom Advertiser of October 15, 1918, focussed on practical measures to contain the infection: rooms should be flushed with fresh air; overcrowding and large aggregations in one room ‘especially for sleeping’ should be avoided; ’invaded places’ should be wet cleaned; ‘indiscriminate expectoration’ (spitting) was not encouraged; as far as possible people should minimise mental strain, fatigue and their alcohol consumption; and should avoid infecting others by leaving the house when showing symptoms.

“A disinfectant gargle of a solution of potassium permanganate in salt water was to be used night and morning, the liquid also to be snuffed up through the nostrils and out through the mouth.

“Local Medical Officers of Health repeated this advice, with a few variations. Face masks were much in evidence in public places and the Surrey Advertiser of November 6, 1918, carried an advertisement for ‘telephone shields’.”

Local newspapers were awash with advertisements for medicines, compounds and “cures” for the deadly disease and Surrey In The Great War – A County Remembers gives a good account of some of these that its researchers have discovered, quoted here.

“The makers of Jeyes’ Fluid urged that it be sprayed in rooms and used in cleaning baths, toilets, and, drastically diluted, as a gargle and to rinse nasal passages (Surrey Mirror, October 25, 1918, and March 7, 1919).

A couple of bars of Lifebuoy soap impressed with the slogan ‘for health’.

“Lifebuoy soap was also presented as a weapon against the ‘scourge’ (Surrey Mirror, March 21, 1919).

Early 20th century medicine bottles. From left: Warner’s Safe Cure (little more than a quack cure); H. Jeffries, Chemist, Guildford; Littleboy Chemist, Woking; and Veno’s Lightning Cough Cure.

“Veno’s Lightning Cough Cure and Nostroline were widely promoted as effective against influenza.

The fluid beef drink Bovril was hugely popular. However, at the time of the Spanish flu pandemic there was a shortage of bottles to put it in.

“Bovril Ltd apologised for a lack of supplies because of a shortage of glass bottles, thus depriving the war-weary and run-down population of its ‘body-building powers’.

“Other popular restoratives, which were supposed to enrich the blood, ward off infection and aid recovery included Hall’s Wine and ‘Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People’. None was effective and people might have been better advised to take the advice contained in the Surrey Mirror of July 26, 1918 and take up cycling to ‘repel the attacks of the insidious germ’.”

It is recorded that there were four waves of Spanish flu, the last being in 1920.

My thanks to Mark Coxhead, who often visits the Surrey History Centre (but closed at present) looking at back copies of the Woking News & Mail on microfilm for snippets of local history that I include in my weekly column, Peeps into the Past, in the current Woking News & Mail. Mark found and copied for me the Surrey Advertiser story of October 26, 1918, shortly before the current lockdown.

Some of my recent stories can be found on the Woking News & Mail’s website, click here for the latest (May 17).

More information on the Spanish flu pandemic on the Sky History website.

Worth watching on BBC iPlayer is the documentary The Flu That Killed 50 Million, narrated by Christopher Ecclestone. First broadcast in 2018, it contains a warning from scientists saying a pandemic was due.

Responses to How The Spanish Flu Pandemic In 1918 Was Reported In Surrey

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

"Found any?" - "Nope, it all looks green to me!" (See Opinion: The Future is Congested, the Future is Grey)

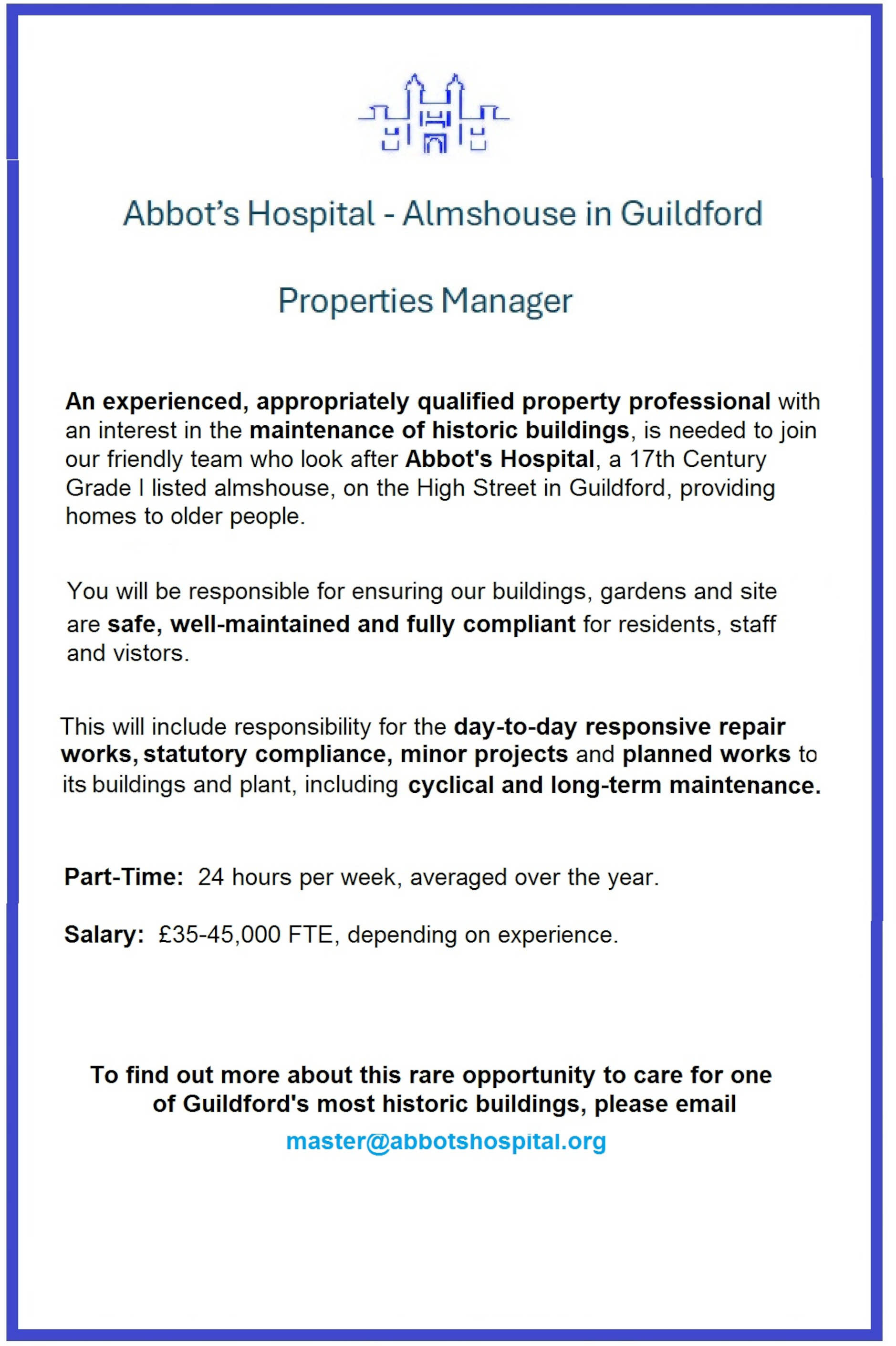

www.abbotshospital.org/news/">

Recent Articles

- Latest Evidence in Sara Sharif Trial

- Ash’s New Road Bridge Is Named – and November 23rd Is Opening Day

- Class A in Underwear Leads to Jail Sentence

- Historical Almshouse Charity Celebrates Guildford in Bloom Victory

- Notice: Shalford Renewable Showcase – November 16

- Firework Fiesta: Guildford Lions Club Announces Extra Attractions

- Come and Meet the Flower Fairies at Watts Gallery

- Updated: Royal Mail Public Counter in Woodbridge Meadows to Close, Says Staff Member

- Letter: New Developments Should Benefit Local People

- Open Letter to Jeremy Hunt, MP: Ash’s Healthcare Concerns

Recent Comments

- Paul Spooner on Ash’s New Road Bridge Is Named – and November 23rd Is Opening Day

- Harry Eve on Opinion: The Future is Congested, the Future is Grey

- Nigel Keane on Letter: New Developments Should Benefit Local People

- Nathan Cassidy on Updated: Royal Mail Public Counter in Woodbridge Meadows to Close, Says Staff Member

- T Saunders on Opinion: The Future is Congested, the Future is Grey

- Jim Allen on Updated: Royal Mail Public Counter in Woodbridge Meadows to Close, Says Staff Member

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Jim Allen

May 19, 2020 at 4:39 pm

Jeyes Fluid, the strongest and best way to stop people hanging around doorways and alleyways in any town centre.