Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Opinion: Thoughts of a Ragged-Trousered Economist

Published on: 2 Dec, 2019

Updated on: 4 Dec, 2019

By Nick Werren

By Nick Werren

This article, edited by The Guildford Dragon NEWS, is taken, with kind permission, from the University of Surrey’s student Incite magazine where it was first published.

A few weeks ago, I was in Marks & Spencer. I don’t get paid much, my rent is high, and my trousers had rips in all the wrong places. I was wondering if I could justify buying a new pair.

I saw only three ways:

1) Save money and wear old clothes till I emerge naked from the rags like a grotesque unwinged butterfly;

2) Buy jeans and save on my weekly food shop by making vast quantities of soup; or

3) Abandon society, live in the hills and build a new society with squirrels not shocked by naked truths.

From the depths of my subconscious a voice muttered: “If I could live in a world where buying a pair of black jeans wasn’t a big financial decision, that would be cool.”

I bought them and ate watered soup for two weeks. That did not dilute my need to write about our national economy.

Our discussions on fiscal policy have been reduced to two phrases: “austerity” and “magic money trees”. Austerity describes the reduction of public services and assets as the government seeks to cut debt, now at an eye-watering £1.8 trillion [1].

That’s approximately 85% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product, the value the entire UK collectively generates every year through provision of goods and services).

The amount the government borrows to spend on public services is only 1.1% of GDP [2].

The difference between what the government spends and what it collects (for instance, through taxes) is the dastardly deficit that recent chancellors have spent much of their time talking about and trying to reduce.

At the same time, private listed companies increase their borrowing, now at 21% of GDP [3]. It’s easier for companies to borrow to fund expansion than spend their assets, particularly in the present economic climate.

Almost magically, now sprouts the magic money tree, political jargon for increased government expenditure on the public sector, clashing with the philosophy of austerity.

Almost magically, now sprouts the magic money tree, political jargon for increased government expenditure on the public sector, clashing with the philosophy of austerity.

But, before we leaf through the branches of this magic money tree, we have to ask how did public debt get so large?

Our national debt increased from 38% to 83% of GDP between 2007 and 2012, and has remained relatively stable since.

That five-year period encompasses a global financial crisis, triggered by the collapse of the American real estate market, caused by their financial institutions giving extremely risky mortgage loans.

As corporate investors realised the loans would not be repaid, money vanished from the economy which created global junk bond shockwaves.

The bubble was bursting and someone had to fill the vacuum. The UK went into a recession as house prices fell, corporation tax dropped, and the government ploughed taxpayer money into the collapsing economy in a desperate attempt to save jobs and prevent further damage.

The people sacrificed a massive increase in debt to ensure private shareholders got returns on their dangerous investments. Since then, some

of the loans have been sold back to the market and conservative estimates place the present taxpayer loss at £27 billion [4].

After the 2008 recession, austerity was inflicted on the new economic landscape and there are claims this led to the deaths of 150,000 people [5]. Was austerity the only option?

Despite what present Chancellor Sajid Javid says, austerity persists and continues to make life difficult for people. Only 0.37% of disposable household income goes on savings [6].

This year, student debt hit £121 billion and shows no sign of slowing [7]. In two more decades, unless the government changes policy, student debts will begin to be written off and hundreds of billions will evaporate from our economy.

The alternative is a transformative vision from Labour, whose radical manifesto would dramatically increase public spending, provide the people with public sector employment, housing, regenerated infrastructure, and a green industrial revolution.

That would be very expensive.

The Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats are offering a brand of “austerity-lite” economics. The significant difference between the two is that the Conservatives want to strengthen relations with markets outside the EU, and Liberal Democrats wish to remain in the EU and spend the money saved on public services.

Both agree Labour’s public spending is dangerous to our economy.

In the 1930s, America experienced an economic cataclysm, known as the Great Depression. Uncontrolled speculative investment in Wall Street led to a spectacular market collapse and a stagnating economy.

Two inseparable economic events followed, the New Deal and the Second World War. The war created an opportunity for the government to expand the war economy with public debt, establishing a public sector reliant on conflict.

The New Deal was a project initially pushed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt for America to recover from the Great Depression.

This project involved massive increases in public expenditure to boost the economy and generate employment. Included were policies such as higher tax rates for the rich, and the creation of economic infrastructure to support homeowners through the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC). Government revenue increased and the Great Depression ended thanks to public spending initiatives and imperialistic foreign policy.

I bring up this example first, to demonstrate that public spending isn’t something for us to be scared of as we approach the General Election.

But second, and more importantly, we must confront our use of economic parameters to quantify the wellbeing of our communities.

Despite protecting people from becoming homeless, the HOLC was infamous for its racist regulations and for intentionally creating slums.

Government initiatives are not immediate solutions to structural discrimination. The Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties were architects of austerity, racist in its own horrible way, and therefore neither party has the moral authority to criticise the “dangers” of public spending.

But the Labour Party’s overhaul of the economy will not cure us of the systemic issues embedded in the structures that compose and control our economy.

Throughout this article, I have used GDP as a measure of economic prosperity because it is the international standard.

Its ability to capture useful information is lauded by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), used by nations in the Global North to exert power over the Global South and strip them of their assets, their labour, and their freedom.

GDP fails to capture the well-being of the people it seeks to understand because that isn’t seen as important.

When you read the party manifestos this year, consider who is brave enough to suggest a better world exists outside of our own. The economy is an important issue, it should affect your vote and it could make your life better, but we must look beyond it.

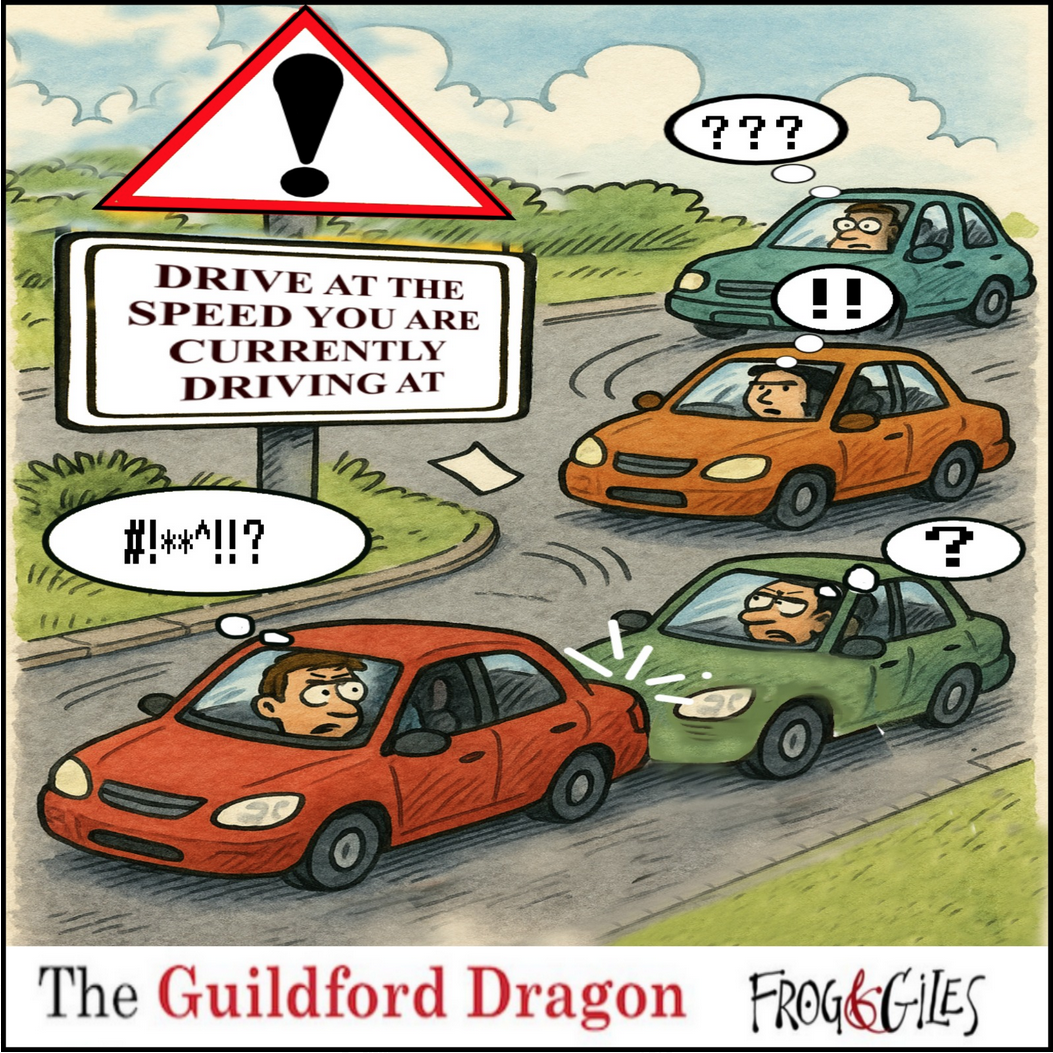

Click on cartoon for Dragon story: Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

Recent Articles

- Updated: Local MPs Vote in Favour of Assisted Dying

- Guildford Plans Three-Day Celebration In a Festival of History And Culture

- Local Therapy Garden Supporting Mental Health Shortlisted for BBC Award

- Thousands of Year Six Pupils at Guildford Cathedral for a Special Send Off

- New Surrey Research to Find Solutions to Local Challenges

- Comment: What Are We To Make of the GBC Executive ‘Reshuffle’?

- Bensons for Beds Opens New Store on Guildford High Street

- ‘Politics Is Not Always a Kind Place’ Says Dismissed Lead Councillor

- Merger Between Reigate & Banstead and Crawley Councils Ruled Out

- Letter: It’s Almost Like We Have Been Abandoned By the Council

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments