- Stay Connected

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

The Story of the Great St Catherine’s Tunnel Collapse on Saturday, March 23, 1895

Published on: 9 Apr, 2020

Updated on: 9 Apr, 2020

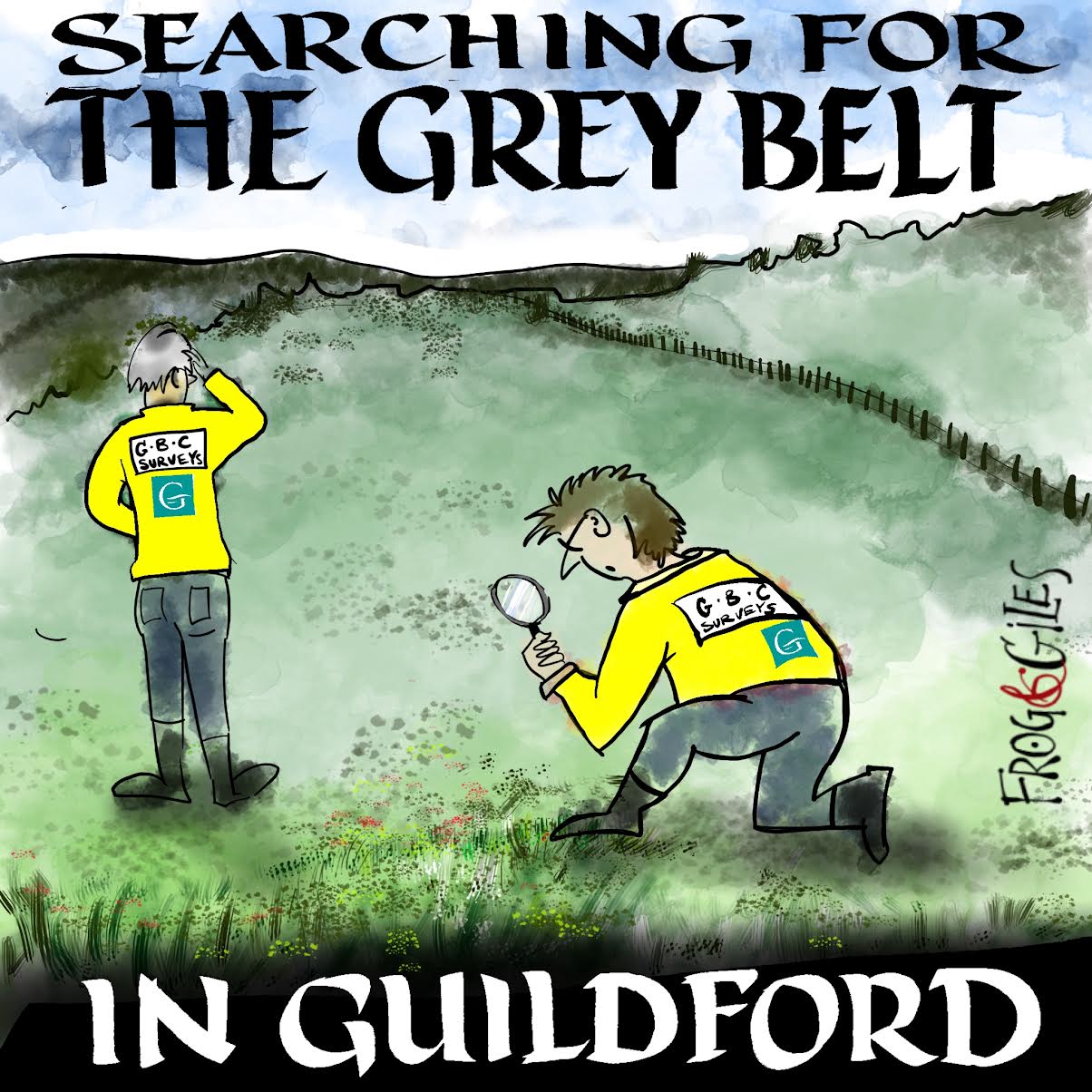

St Catherine’s Railway Tunnel Collapse

The discovery of what appears to be a historic cave above the railway tunnel at St Catherine’s Hill has led historian Frank Phillipson to recall the late 19th century sand tunnel collapse…

In 1849, the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) extended their line from Guildford to Godalming (Old Station). The extension required the boring of two tunnels, the first being the longer chalk tunnel immediately south of Guildford station and the second, the shorter one through the sand that makes up St Catherine’s Hill.

The Board of Trade inspector was sceptical about the condition of this second tunnel when he viewed it in August 1849 before opening for use. A couple of months later, there was a fall of sand which was cleared away.

Then at 11:40pm on Friday, March 22, 1895, an empty passenger train left Petersfield and was to arrive in Guildford at 12.20am on Saturday, the 23rd. The train, with driver Sherwin, fireman Stiles and guard Wilde, was more than halfway through the St Catherine’s tunnel when the bogie tank engine ran into a mass of bricks and debris fallen from the roof at the north end of the tunnel. The first two coaches piled up and smashed behind the locomotive.

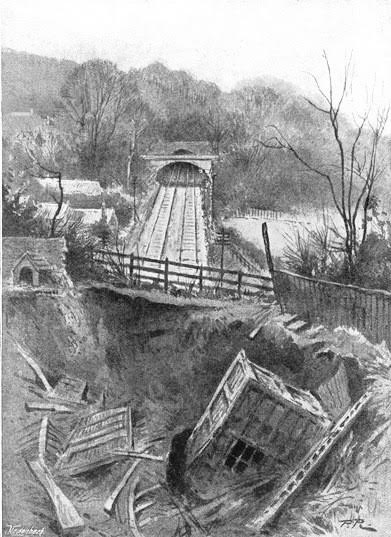

The sinkhole left above the collapsed tunnel and beyond looking north, the line continuing towards the chalk tunnel and Guildford Station.

The engine crew rapidly extinguished the engine’s fire and made a hasty retreat with the guard from the tunnel. Soon after, there was a further, larger roof fall which buried the engine and the front part of the leading carriage. The three railwaymen, severely shaken, cut and bruised, were taken by cab to the Royal Surrey, on the Farnham Road, for treatment.

Above the collapse point had been a coach-house and stable with stalls for three horses. These, with two horses and four carriages, had all been swallowed by the subsidence. The local policeman, PC Tickner, helped by men from St Catherine’s Village and the house the stables belonged to, tried to rescue the horses but that proved impossible because they were deeply embedded in the mass of sand.

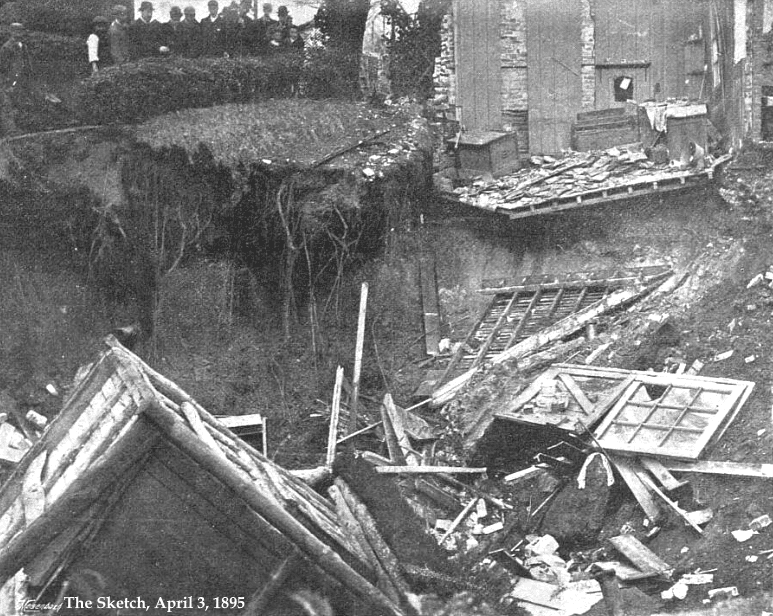

A tangled mix of bricks, woodwork, sand and roots. Note the onlookers at the top. Placing cordons to keep spectators at a safe distance seems a fairly modern practice.

All that could be seen from above then was a hole filled with a tangled mix of bricks, woodwork, sand and roots with a toppled wooden summerhouse on top. The horses, carriages and buildings belonged to Dr Horace Wakefield’s house, “The Beacon” on the eastern side of the hole, which had survived intact.

The collapse meant all services from Guildford to three different routes south of the tunnel were suspended. A Mr Stredwick, the district railway permanent way engineer, was quickly on the scene and soon had about 100 men helping shore up the hole with large timbers.

By late morning, the railway workmen had started building a long temporary platform at the tunnel’s south end so trains to and from the south could stop to allow passengers to alight or board. These passengers would be conveyed by horse buses and cabs to and from Guildford station.

On Tuesday, after the carriages had been removed, two locomotives tried to pull out the embedded engine but the couplings broke on the second attempt. That day the two horses were dug out and buried.

By Thursday, the 24-hour shiftwork had cleared the line and it was now possible to walk through the tunnel. Workmen found the only way to remove the engine was to dig out the sand around it altogether. The same day, a live cat entombed for five days was discovered.

Mr Stredwick had hoped that by Monday to start running trains through the tunnel again although this would be on only a single line, not the usual double track. There would be a temporary signal cabin at each end of the single line and trains would proceed only very slowly.

Some thought the tunnel would be rebuilt where it collapsed and that a relieving arch would be added inside part of the tunnel south of the collapse to strengthen it. But inspection showed the St. Catherine’s sand weighed 100lbs per cubic foot and this would take a further 19lbs of water which did not percolate through very quickly.

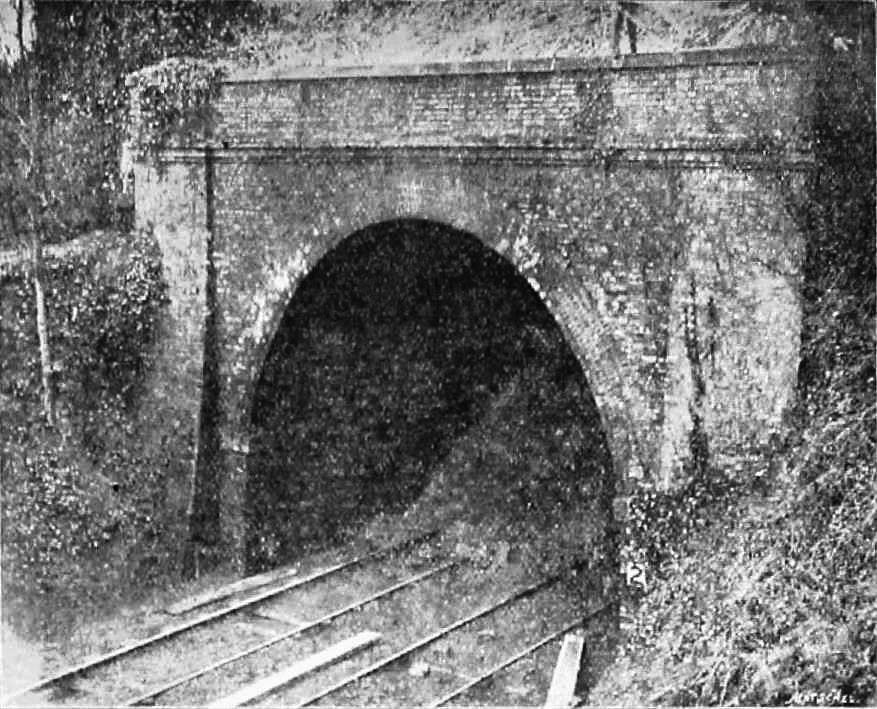

The sand within the tunnel can be seen in this photograph.

The Board of Trade investigating inspector, Major Francis Marindin, stated in his report that the tunnel had a high elliptical arch of brick and mortar with a six-ring lining of brick. In the area of the collapse from the top of the arch to the surface was 27ft and generally the tunnel was dry apart from a few wet patches south of the collapse.

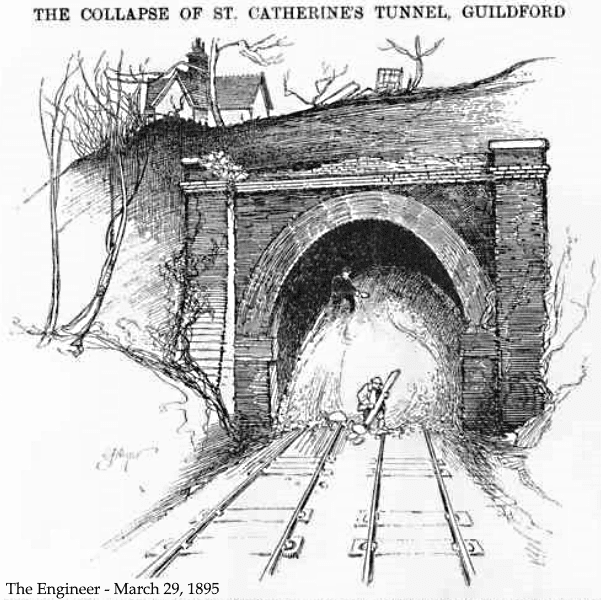

An artist’s impression of the same scene.

The permanent way ganger in charge of the line through the tunnel, who examined the line twice a day, stated that there had been no indication of any failure or dripping water in the vicinity of the collapse when he walked through on the previous evening.

Within the brick arch revealed by the fall there were shown to be a few rotten timbers used in the construction of the tunnel. But they reduced the thickness of the tunnel lining by only one brick of the ring of six and although slightly reducing the strength of the arch did not significantly play a part in the collapse. Being rotten, what they did do was to form channels which allowed water to flow and percolate through.

Major Marindin found the removed sand to be quite dry. But he was told that at the time of the collapse the spoil that fell through was so completely saturated it formed a slurry which splashed up to the top of the arch when the locomotive hit it. The railway engineers believed this saturation was due to leakage from drains and cesspits of “The Beacon” and possibly a broken water pipe.

Major Marindin found the removed sand to be quite dry. But he was told that at the time of the collapse the spoil that fell through was so completely saturated it formed a slurry which splashed up to the top of the arch when the locomotive hit it. The railway engineers believed this saturation was due to leakage from drains and cesspits of “The Beacon” and possibly a broken water pipe.

The inspector also found water percolation had caused a cavity to form above the brick lining which, as it increased in size, loaded the brick arch unevenly and eventually led to the collapse. He said this must have taken a considerable time without showing any signs in the tunnel below so test pits should be dug all along the tunnel to check for further cavities and similar soil conditions. He felt the whole tunnel should have a reinforcing brick arch constructed.

A newspaper report of June 22, 1895 states that the directors of the railway “have decided to abandon the use of the tunnel at this point of the line and substitute a cutting”. Obviously, this did not happen.

Concerns were raised that collapse also made the foundations of St Catherine’s Chapel very insecure and many feared the 14th-century historic landmark could be lost, so the railway company’s directors ordered necessary steps to safeguard the building.

See also: Revealed: Markings Inside the Mystery Medieval Cave Found at St Catherine’s Hill

Alan Cooper

April 19, 2020 at 9:55 am

What a fascinating and interesting article. I had no idea of this problem with second tunnel. Great old photographs as well.