Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

XX Notes: How Can These Exam Results Truly Reflect Pupils’ Abilities?

Published on: 15 Aug, 2020

Updated on: 15 Aug, 2020

Maria Rayner‘s observational, fortnightly column from a woman’s perspective…

I don’t remember opening the O-level results envelope but I do remember going to my school to double-check the results: As and Bs were not common at my Cornish comprehensive in the Eighties.

A brand new school, it was set on top of a hill overlooking the market town. With the recently planted trees still saplings, it was a bleak spot even on an August drizzly day.

If I was incredulous over my results I was completely flabbergasted over my classmate’s. He had been in one or other of my classes ever since we had joined the school five years previously but had slid down the teachers’ rankings as he had climbed up the unofficial cool leaderboard. An undeniably bright boy, he approached two years of O-level study with all the industriousness of Bart Simpson. How come he had passed all his exams with Cs (a good result back in the day)?

This was before schools had cottoned on to the media exposure that pretty girls jumping with glee holding bits of paper in their hands could attract, so there was no one else about to share my joy or astonishment; I went home puzzled.

Years later and a teacher myself, gave me plenty of experience of the boys who did no work all year and relied on cramming for exams to gain their qualifications.

In the Nineties, with 100% coursework GCSEs, they lost out and girls began to out-qualify boys on the attainment chart – girls being more likely to work hard all year round.

It’s very difficult to cram two years work into a few months – I tried with a ‘bottom’ set who’d been written off by their previous teacher. They all got an English GCSE, which was more than they would have if they’d still been taught English by the metalwork teacher – it was a South London ‘sink’ school.

As the Nineties progressed and the various revisions of the National Curriculum altered the balance of coursework to exam I saw many boys get higher grades than their classwork would have predicted.

And it is with this experience that I view the various exam results coming out from all over the UK. I’m not going to comment on the various U-turns, algorithms and political posturing – my article would be out of date within 24 hours. What I am going to say is: how can these results possibly be a true reflection on the abilities and potential of this cohort of our children? – As I recognise that my generalisation of boys cramming is also common among girls. Ask any journalist; I’m typing up to the deadline right now!

News website Schoolsweek reports that the trend of girls attaining higher grades at A-level has meant that they have now outstripped boys in England, ‘up from 25.1 % last year, compared with 27.1% of boys, up from 25.2% last year’.

News website Schoolsweek reports that the trend of girls attaining higher grades at A-level has meant that they have now outstripped boys in England, ‘up from 25.1 % last year, compared with 27.1% of boys, up from 25.2% last year’.

How much of this statistic is due to the teachers having more evidence of the attainment of girls? And what will this mean for next week’s GCSE results for boys?

Next week, when I’m looking at the GCSE stats from schools that teach disadvantaged children, I’ll be thinking of a boy called Ben, who worked so hard to get his A when the rest of his year group would be lucky to scrape a pass.

A girl called Joanne, who pulled out all the stops to get a C in English because she could see she was valued in my classes, not elsewhere in the school, sadly, which reflected in her results.

Hussain, who arrived from Somalia with no English but fluent in Italian but was finally able to communicate to me about his grandfather who was a newsreader on Somalian TV.

And the special teachers who worked so hard every day to deliver lessons to classes of troubled teenagers.

There are so many articles assessing which types of schools or colleges have been most affected by the algorithms and moderation but behind all of the facts and figurers are real live children with real live fears, hopes and dreams, not made any easier by Covid.

The truth is that none of this situation is fair. My youngest son is due to get his GCSE results next week. Fortunately he got great results for his mock exams, but my teacherly rule of thumb is that with Easter ‘sprint finishes’, more focused revision and unbiased marking (not marking strictly to encourage more detailed revision) is that the summer mark is a grade higher.

The truth is that none of this situation is fair. My youngest son is due to get his GCSE results next week. Fortunately he got great results for his mock exams, but my teacherly rule of thumb is that with Easter ‘sprint finishes’, more focused revision and unbiased marking (not marking strictly to encourage more detailed revision) is that the summer mark is a grade higher.

Like his schoolmates, he’s been robbed of the chance to really prove his knowledge. Luckily for him he is staying on at his school to study A-levels so his GCSEs will hopefully be surpassed by A-level qualifications, but what of the Joannes and Hussains?

They will face an uncertain future with what is frankly an incomplete education and it is not a realistic solution to just simply sit the exams in September, or October having had no schooling since March, despite the ill-considered comments of the twitterati.

Responses to XX Notes: How Can These Exam Results Truly Reflect Pupils’ Abilities?

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

"Found any?" - "Nope, it all looks green to me!" (See Opinion: The Future is Congested, the Future is Grey)

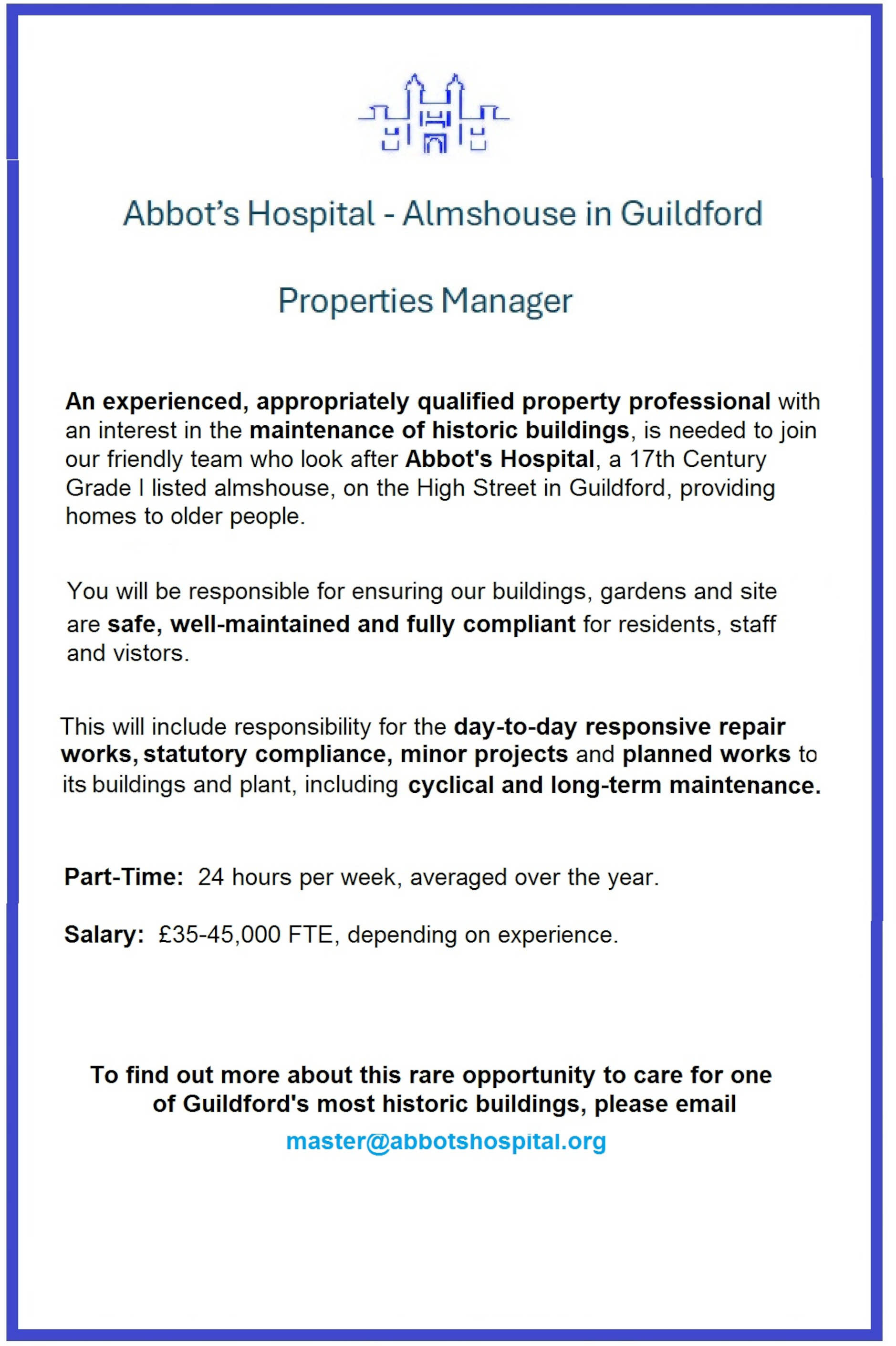

www.abbotshospital.org/news/">

Recent Articles

- Firework Fiesta: Guildford Lions Club Announces Extra Attractions

- Come and Meet the Flower Fairies at Watts Gallery

- Royal Mail Public Counter in Woodbridge Meadows to Close, Says Staff Member

- Latest Evidence in Sara Sharif Trial

- Letter: New Developments Should Benefit Local People

- Open Letter to Jeremy Hunt, MP: Ash’s Healthcare Concerns

- Opinion: The Future is Congested, the Future is Grey

- Full Match Report: City Go Out of FA Vase on Penalties

- Letter: Incinerating Unnecessary Packaging Causes Pollution

- Letter: Thank You, Royal Surrey

Recent Comments

- David Chave on Did You See Punk Band The Clash At Guildford Civic Hall in 1977?

- Olly Azad on Full Match Report: City Go Out of FA Vase on Penalties

- Ben Paton on Opinion: The Future is Congested, the Future is Grey

- N Rockliff on G Live Brings More Classical Concerts to Guildford from Renowned Orchestras

- Paul Duggen on Woking Councillors Refuse School Expansion Proposal

- Susan Smith on Birdwatcher’s Diary No.314

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Anthony Mallard

August 15, 2020 at 4:46 pm

The government has set up a hugely bureaucratic system to get itself out of a problem of its own making.

Showing similar incompetence to the management of the COVID crisis, where lack of clarity means no one knows who can do what with whom and for which there is no-one to appropriately enforce the self-isolation or other guidance anyway.

Surely, the simple answer to the recent examination chaos would have been to postpone the universities academic year to January and for students to sit their examinations in, say October/November, having returned to full time education in September.

John Morris

August 15, 2020 at 9:36 pm

My answer to Maria Rayner’s title question, “How can these exam results truly reflect pupils’ abilities?” is “They can’t” – and never can.

The aim of school examinations has always been to produce a rank order of examinees according to very limited subject criteria. That then is supposed to make life simpler for hard-pressed university and college admissions tutors and employers trying to make some initial selection of job applicants. The thinking is that a student with an “A” is somehow “better” than one with a “B”.

This year’s enormous additional problems have merely highlighted that perennial one with school examinations and their testing of very limited ranges of skills and knowledge.

Now is definitely the time to replace school examinations which, like the pet’s tail, inevitably “wag the learning dog”. Education should not be “schooling” – fitting children and adults into a straightjacket of society’s expectations or of fitting young people to be that society’s little cogs.

Education should be a joyous celebration of learning, of learning more and more about people and the extraordinary world in which they live.

Let’s abandon cramming, qualifications and rankings once and for all. Examinations can never, as Maria Rayner says, describe anyone’s fears, hopes and dreams, neither can examinations ever be fair.

John Morris is a member of the Peace Party and general election candidate.

John Perkins

August 16, 2020 at 6:10 pm

Exams are far from perfect and I don’t advocate them, but nor do I know of a good alternative.

Teachers are too subjective (I know from personal experience) and algorithms are repeatedly shown to be unfair.