Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Rare And Historic Guildford Tokens To Be Auctioned

Published on: 4 Dec, 2015

Updated on: 4 Dec, 2015

Rare items representing an important part of England and Guildford’s history are going under the hammer at an auction in London on Monday, December 7.

They are tokens dating back to the 17th century, issued when England was bankrupt at the end of the Civil War. Traders in towns and villages had them made and circulated them as unofficial currency.

In some cases they were certainly used for the relief of the poor.

It’s where the term “so poor, he didn’t even have two brass farthings to rub together,” comes from. Guildford issued two varieties of these brass farthings.

A local collector has put the tokens up for sale at Dix Noonan Webb Ltd, auctioneers in London.

The tokens have been fully catalogued and can be viewed on its website, by clicking here.

Bids can be placed using the auctioneer’s online service.

The Guildford tokens are being offered in three lots (numbers 288 to 290), while other lots (from 281 to 297) feature similar 17th-century tokens from other Surrey towns and villages including Bagshot, Bramley, Cobham, Croydon, Epsom, Farnham, Godalming, Haslemere, Kingston upon Thames, Lingfield, Puttenham, Richmond upon Thames, Shalford, and Walton-on-Thames.

The tokens are particularly interesting, not only for the spellings of place names on them reflecting local dialects of 350 years ago. DARKIN for Dorking, EBISHAM for Epsom, GODLYMAN for Godalming and GILLFORD for Guildford.

Local family names that appear on the tokens can still be found: They include JOSEPH CHITTY, a blacksmith from Bramley and his relative HENRY CHITTY, a grocer in Godalming.

JOHN SMALLPEECE, a Guildford grocer who served his seven-year apprenticeship under both his father and his mother. He also had a sideline hiring out row barges on the river, as illustrated on his tokens.

Many of the Guildford tokens use the symbol of the woolpack, which is taken from Guildford’s coat of arms.

This could have been agreed by the traders among themselves, or more probably the town council encouraged their use to unify and promote the town, even before the town’s issue of its own 1668 brass farthing, which also used the same symbols.

These tokens rarely turn up in beautiful condition, because they were used in a state of emergency. However, they are fascinating items of local history and would perhaps benefit in staying local and even made available for more people to view and hear their story.

Responses to Rare And Historic Guildford Tokens To Be Auctioned

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.Recent Articles

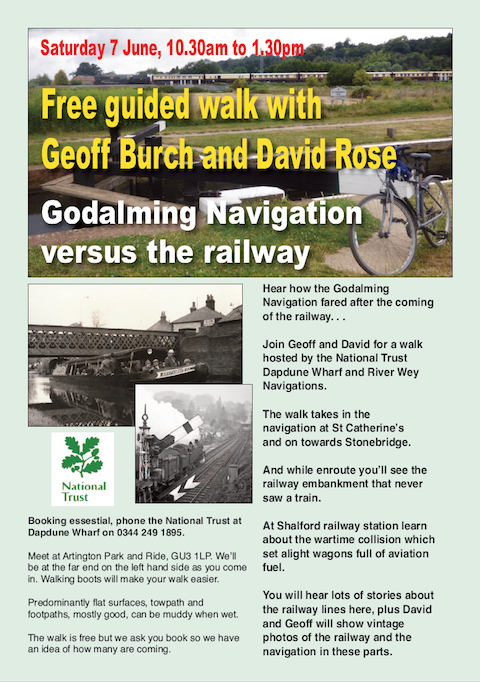

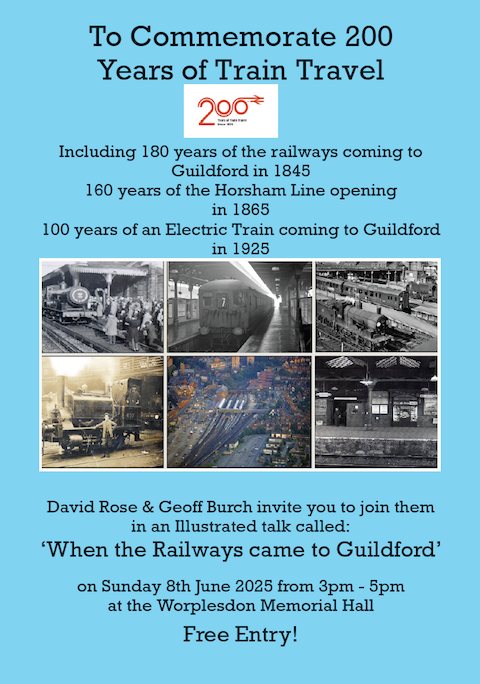

- Major Disruption on the Railway During Hot Day in 1900

- Notice: GTA Exchange Art Exhibition June 18-21

- Letter: I Would Rather Have Potholes Filled

- New Parish Councillor Says Funds from Developers Must Benefit the Local Community

- Tests at Paddling Pool Showed Water Was Too Alkaline, Says GBC

- Letter: Our Residents Want CIL Money Properly Used for Infrastructure Without Delay

- Charity’s New Programme Meets Needs of SEND Children Without School Places

- Pasta Evangelists to Open First Restaurant Outside London – Right Here in Guildford

- Police Seek Witnesses to Park Barn Assault

- Notice: Rosamund Community Garden

Recent Comments

- Warren Gill on Millions of Taxpayer Money Recovered from Railway Fare Dodgers

- Roshan Bailey on Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

- R Wong on Letter: Our Residents Want CIL Money Properly Used for Infrastructure Without Delay

- Nigel Keane on Village School Set to Close Due to Falling Birth Rate

- Patrick Bray on Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

- Mark Percival on Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

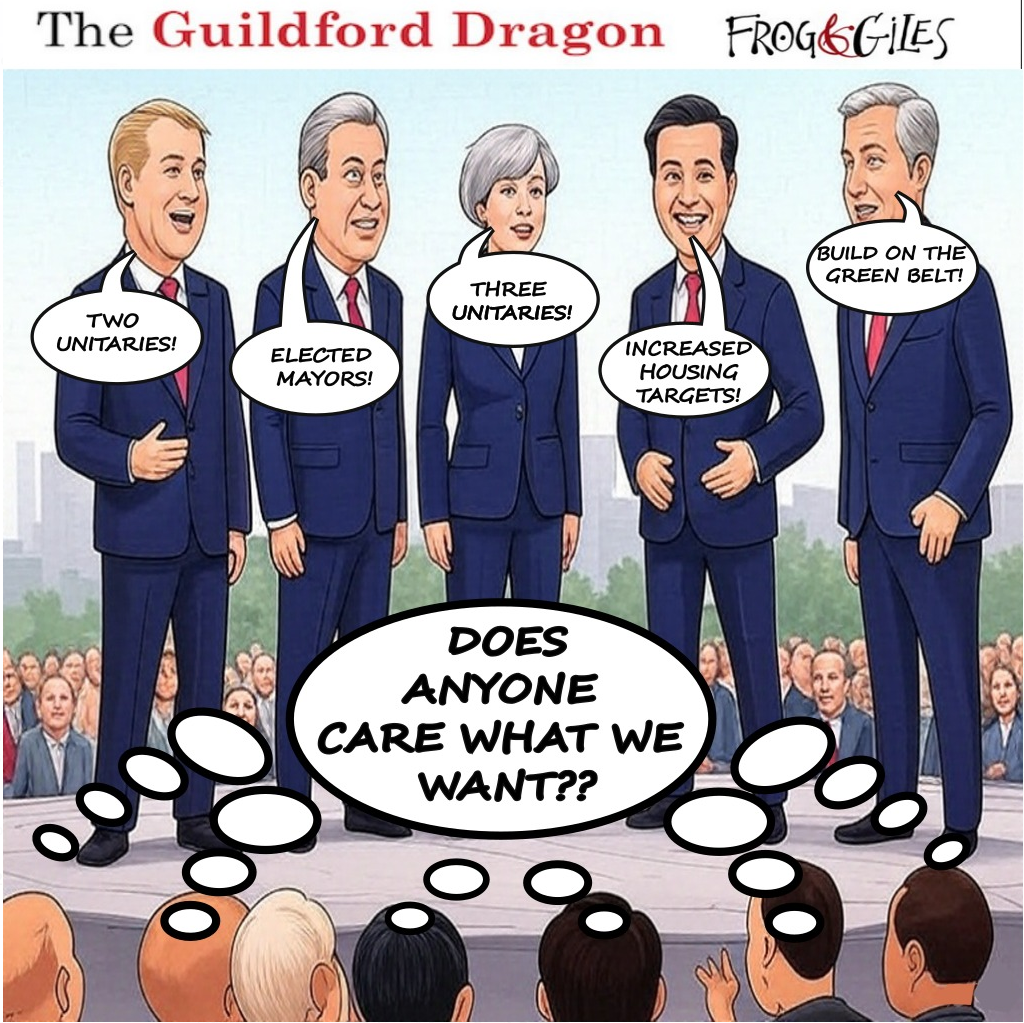

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Barry Williams

December 4, 2015 at 4:15 pm

This would be a great collection for GBC to purchase for Guildford Museum – but I guess our council’s need to reduce museum losses means they do not have two brass farthings to rub together anyway.

Mary Alexander

December 6, 2015 at 8:45 pm

Guildford Museum has an excellent collection of traders’ tokens, thanks to the Surrey Archaeological Society which owns most of them.

It is the best collection of Surrey tokens in a public collection – better even than the British Museum’s collection.

There are only two tokens in the auction which are not in the museum’s collection, from Dorking and Richmond.

Out of over 300 known tokens 30-odd are missing from the museum’s collection.

There are some duplicates in the collection and it would only be worth buying those tokens which fill gaps in the collection, or are of better quality.

The collection covers the whole of the historic county, up to and including Southwark.

Tokens give a fascinating picture of local, social, political and economic history.

They were made because there was a shortage of small change. Coins were made of silver (and gold) and were worth the actual metal in them.

No monarch could bring themselves to make base metal coins (after a false start under James I which confirmed everyone’s suspicions of a token coinage).

However, when Charles I was executed in 1649 the royal monopoly on minting coins ended and someone, somewhere, started to issue the trader’s tokens.

They were understood to represent a farthing, but only a few had this written on them. Very occasionally halfpenny tokens were made.

Most tokens have the trader’s name, his town or village and his trade, either written or shown by a symbol.

A baker might have a sheaf of wheat, a grocer might have a sugar loaf, or the arms of the London Grocers’ Company, an innkeeper would have the name of the inn and an image such as the Red Lion.

Sadly, most Guildford tokens had the same designs of the castle or a woolsack, and a slightly mysterious set with the (supposed) arms of Edward the Confessor and the initials F.M.F.S.

Only John May had a sign of his trade of shoemaker, by putting a last on his token.

John Smallpeece’s row barge may be a sign of pride in the new trade along the Wey Navigation which brought him goods to sell from London.

Single women working alone issued tokens, and many men put the initials of themself and their wife on the token, showing how closely involved the wife was with the family business.

They ceased to be made after 1672 when Charles II introduced an official copper coinage.