Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

A Visit to the Grave of the Zeppelin Commander Who Inflicted ‘A Night of Terror’ on Guildford

Published on: 4 Aug, 2023

Updated on: 7 Aug, 2023

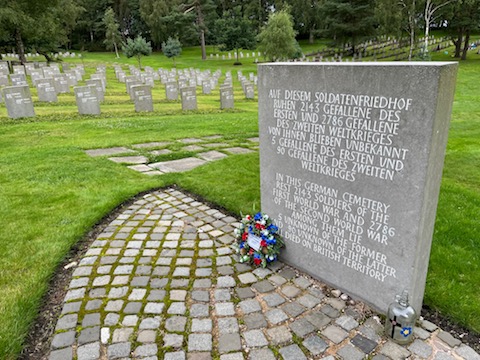

The Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery.

By David Rose

On a recent trip to Staffordshire, I took the opportunity to visit the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s (CWGC) Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, to locate the final resting place of First World War German Zeppelin commander Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy.

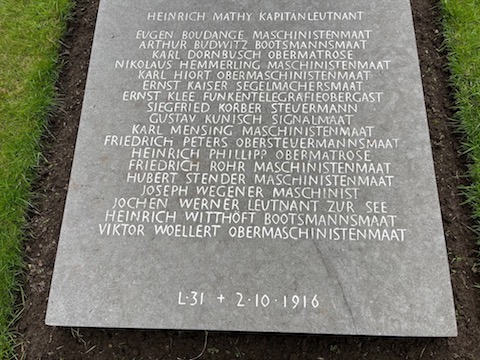

The grave of Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy and his crew of the L31 Zeppelin.

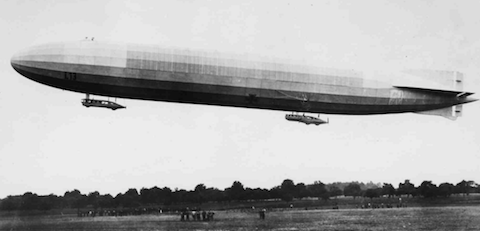

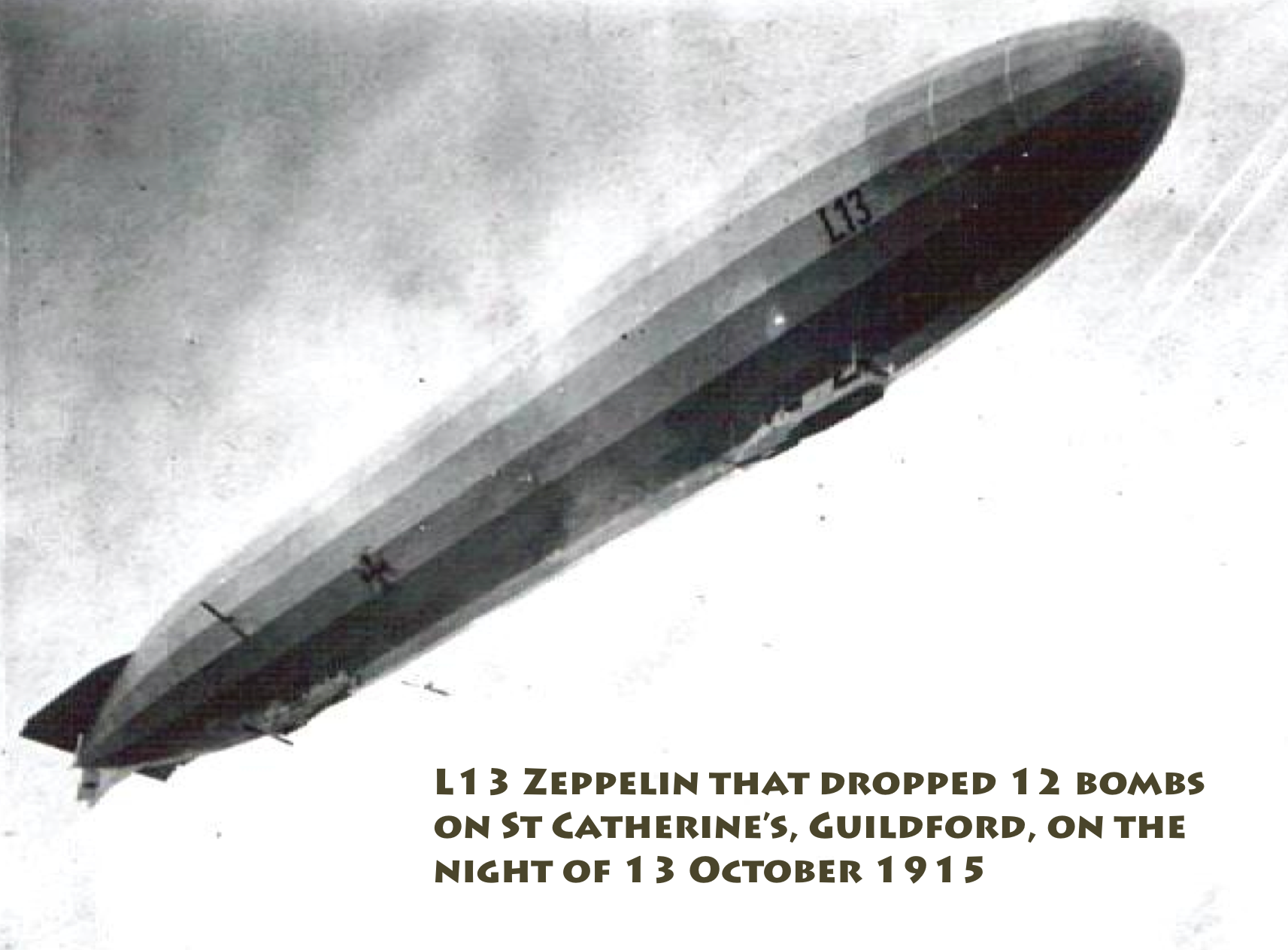

The reason being that on October 13, 1915, a German Zeppelin airship inflicted a ‘night of terror’ when it circled over Guildford and dropped 12 bombs over St Catherine’s Village and the River Wey.

The full story has been told on the Dragon previously in Terror Zeppelin Raid On Guildford Was 100 Years Ago and Letter: Further Thoughts On The L13 Zeppelin Raid in 1915.

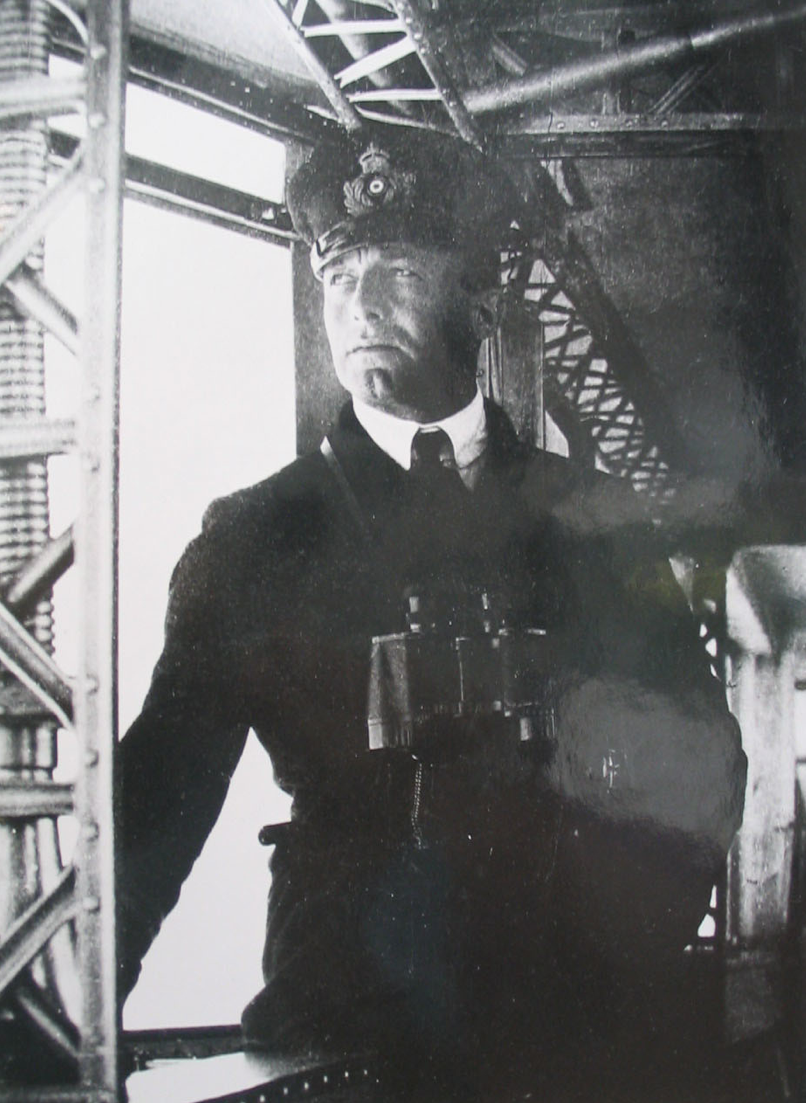

The commander of the L13 Zeppelin on that night was Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy. He he was one of very few Germans whose names were household words in Britain during the First World War.

His notoriety came about during what was known as the “Zeppelin Scourge” of 1915 and 1916. It’s been said that Mathy was known and feared as the most daring and audacious of all the Zeppelin raiders.

However, Mathy’s luck was not to last. Once incendiary bullets had been developed and supplied to British night-fighter aircraft, it was possible to shoot down in flames German airships.

He met his fate when in charge of the L31 Zeppelin during a raid on the night of October 1-2, 1916.

The L31 Zeppelin.

A page on the website gwpda.org about Mathy and his career in the German Navy, that operated airships, gives details of how he met his death.

It states: “Mathy was shot down in flames by Second Lieutenant W. J. Tempest. The ship fell just outside Potters Bar, to the north of London.

“Mathy’s body was found some way from the wreckage of the ship, half-embedded in the corner of a field. Obviously, his last act had been to leap clear of the falling inferno rather than wait for the crash. According to some accounts, he lived for a few minutes after striking the earth.

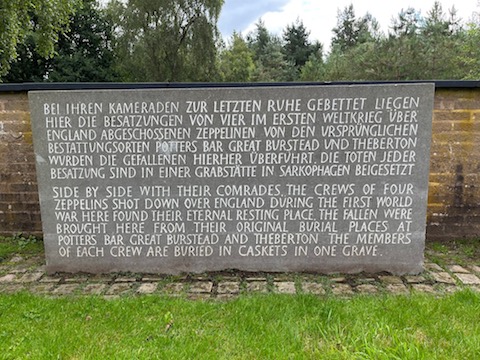

“Originally buried [in the local churchyard] at Potters Bar, the bodies of Mathy and his crew were moved in the early 1960s to Cannock Chase in Staffordshire, where a new cemetery had been constructed for the burial of all Germans from both world wars [excluding those already buried in CWGC cemeteries] who died on British soil.

“He lies buried there with his crew, near the entrance, along with the commanders and crews of the other three airships which were shot down over England.”

Memorial stone at the cemetery giving details of the four graves of Zeppelin crews.

An even more detailed biography of Mathy and the story of the removal of the remains of Mathy and his crew from Potters Bar to the Cannock Chase German Cemetery can be found on the Hellfirecorner.co.uk website.

The four graves of the Zeppelin crews.

This military cemetery is fascinating. Its page on the CWGC’s website states:

“On 16 October 1959, an agreement was concluded by the governments of the United Kingdom and the Federal Republic of Germany concerning the future care of the graves of German nationals who lost their lives in the United Kingdom during the two World Wars. The agreement provided for the transfer to a central cemetery in the United Kingdom of all graves which were not situated in cemeteries and plots of Commonwealth war graves maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in situ.

“Following this agreement, the German War Graves Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgraberfursorge) made arrangements to transfer the graves of German servicemen and civilian internees of both wars from scattered burial grounds to the new cemetery established at Cannock Chase.

“The inauguration and dedication of this cemetery, which contains almost 5,000 German and Austrian graves, took place in the presence of Dr. Trepte, the President of Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgraberfursorge, on the 10th June 1967.

The Hall of Honour at the cemetery.

“In the centre of the Hall of Honour, resting on a large block of stone, is a bronze sculpture of a fallen warrior, the work of the eminent German sculptor, Professor Hans Wimmer.”

Young volunteers from Staffordshire and Germany helping to maintain the cemetery.

While we were at the cemetery, young volunteers from local schools in Staffordshire and a party of German students were busy helping to maintain the cemetery and cleaning the headstones. This appears to be an annual event organised by the CWGC.

The cemetery is situated in a secluded spot surrounded by pine trees, on heathland.

Responses to A Visit to the Grave of the Zeppelin Commander Who Inflicted ‘A Night of Terror’ on Guildford

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.

Click on cartoon for Dragon story: Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

Recent Articles

- A281 At Shalford Has Now Reopened Following Repairs To Damaged Roof

- Frimley Park at the Beginning of the Hospital Rebuild Queue

- Letter: Council Has Quietly Relieved Developer of £Million Obligation

- The Royal Surrey Hospital to Open Its Doors to the Public for Community Open Day

- Summary of GBC Planning Decisions – June 18, 2025

- Letter: Reflecting on the Juneja Case Shows the Importance of the Monitoring Officer Role

- New Electric Trains Now Arriving at Guildford – 100 Years After the First One Did

- Woman Pedestrian Dies on A31 After Collision With a Truck

- Road Closed After Lorry Hits Railway Bridge

- The Bishop’s Leap of Faith – From the Top of the Cathedral

Recent Comments

- H Trevor Jones on Residents Urged to Have Their Say on the Changing Shape of Surrey’s Local Government

- Alistair Smith on A281 At Shalford Has Now Reopened Following Repairs To Damaged Roof

- Roland Dunster on GBC’s Plan For a Thriving Guildford ‘Is Our Promise to Residents’ Says Council Leader

- Richard Benson on GBC’s Plan For a Thriving Guildford ‘Is Our Promise to Residents’ Says Council Leader

- Nigel Base on Letter: Recreational Rowing Might Be the Answer

- Anna Windebank on GBC’s Plan For a Thriving Guildford ‘Is Our Promise to Residents’ Says Council Leader

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Gavin Morgan

August 5, 2023 at 5:19 pm

Very interesting article. My grandmother was 18 in 1916 and recalled sheltering in the entrance of a bank in north London with her father one night when they saw a Zeppelin come down. Looked up the national archives. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/zeppelin-raids/

It says “ British defences learnt to pick up their radio messages, so had warning of their approach, and a central communications headquarters was set up.

At first RFC fighters found it hard or impossible to reach the heights at which the Zeppelins flew but with the advent of the SE5, developed at Farnborough, they could. It was also realised that Zeppelins were extremely vulnerable to incendiary bullets, which set light to the hydrogen, often in spectacular fashion.

Zeppelin raids were called off in 1917, by which time 77 out of the 115 German Zeppelins had been shot down or totally disabled. Raids by heavier-than-air bombers [see Gotha bombers] continued, however.

By the end of the war over 1,500 British citizens had been killed in air raids.”. I didn’t realise there were also raids by planes in World War 1. As a child, I remember my father pointing out what he said was Zepplin raid damage to Cleopatra’s needle on the Embankment in London.

Gavin Morgan is the founder of the Guildford Heritage Forum