Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Terror Zeppelin Raid On Guildford Was 100 Years Ago

Published on: 13 Oct, 2015

Updated on: 14 Oct, 2021

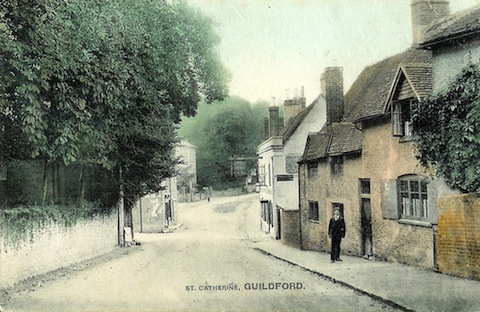

One hundred years ago today (October 13, 1915) Guildford’s suffered its ‘night of terror’ when a German Zeppelin airship circled over the town and dropped 12 bombs, which fell in and around the St Catherine’s area.

Local historians David Rose, Martin Giles and Mike Bennett know the story well. They have given illustrated talks on it based on their research with excellent information supplied by fellow historians Frank Phillipson and Roger Nicholas.

With the story now being told once again there is growing interest to have a plaque placed at a suitable location in St Catherine’s that records the event and that gives some details of what happened. You may like to leave a reply in the box below with your comments and suggest where it could be placed.

Here’s what actually happened and why, republished from David Rose’s latest book Great War Britain Guildford Remembering 1914-18 (published by The History Press at £12.99).

Guildford’s most infamous night during the First World War was on Wednesday 13 October 1915 when a Zeppelin airship of Germany’s Imperial Navy circled over Guildford dropping 12 bombs on St Catherine’s Village and Shalford Park. This was Guildford’s night of terror, and one that anyone who witnessed the events would not have forgotten for the rest of their lives.

That afternoon five airships left their German bases at Nordholtz and Hage. Their aim was to fly over the Norfolk coast and attack London from the north. One airship got lost over Norfolk and headed for home, the others continued and dropped bombs in the London area, but in most cases not near their intended targets. The blackout in force across Britain made navigation extremely difficult.

The commander of the L13 Zeppelin, Heinrich Mathy, was in charge of the whole raid. This experienced and heroic commander and his crew dropped bombs over the site of an anti-aircraft gun near Hatfield in Hertfordshire and then picked up the Thames on their way to attempt to bomb the waterworks at Hampton.

It appears that while over Weybridge Mathy missed a vital bend in the Thames and headed down the River Wey instead, passing places such as Newark and Send.

The L13 reached Guildford at about 10pm, where it circled for a time then flying off in the direction of Wood Street before returning to Guildford and St Catherine’s Village. Once there, a brilliant blue flare was dropped from the airship.

At 10.25pm another flare was dropped that also lit up the sky. Then its bombs were released.

The L13 made off in an easterly direction towards Redhill. It turned towards London again and dropped further bombs on Woolwich Arsenal, mistaking it for the Victoria Docks. Mathy and his crew finally got back to their base the next morning.

The other Zeppelins in the raid dropped their bombs in a variety of locations and caused a good deal of damage. In all they dropped 102 explosive bombs, eighty-seven incendiary bombs, killing seventy-one people and injuring 128. In Croydon alone, fifty-three people died.

It would have been the sound of the airship’s droning engines that people in Guildford would have first heard when the L13 Zeppelin was overhead on that infamous night. Some people may have seen the flares dropped by the Zeppelin’s crew – but just about everybody would have heard the bombs exploding. Those who ventured outdoors would certainly have caught a glimpse of the airship. And the following day, many people went to St Catherine’s to see what had happened.

Mercifully, no one died, but there was a lot of damage to buildings – such as windows smashed and walls that had collapsed, and the main railway was damaged between the two tunnels. But many people would have been suffering from shock – especially those living in St Catherine’s.

The Guildford police constabulary report noted where each bomb fell and the damage done.

Bomb 1: fell in the garden of Little Croft, Guildown Road. It uprooted a large tree and made a crater three feet deep and twenty wide. One hundred and forty-six panes of glass were broken and a garden gate was blown away.

Bomb 2: fell in a field belonging to Braboeuf Farm. It made a hole three feet deep and ten feet wide.

Bomb 3: fell in Chestnut Avenue at the rear of Guildown Grange. It made a hole in the roadway three feet deep and eight feet wide. A wall eight feet high and twenty-one feet long was knocked down. Much damage was done to a greenhouse.

Bomb 4: also fell in Chestnut Avenue, making a hole three feet deep and ten feet in diameter. Thirty yards of garden fencing was blown away.

Bomb 5: fell in garden of St Catherine’s Cottage making a hole three feet deep and twenty feet in diameter. Twenty-two panes of glass were broken in a greenhouse. The roof of house was badly damaged. At nearby Montague House, seventy-four panes of glass were broken. Blast from this bomb also caused damage to Langton Priory (sixty-two panes of glass), and the Anchor and Hope pub where 105 panes of glass were smashed.

Bomb 6: fell at the up side of the railway line about 120 yards from the chalk tunnel. It made a large hole in the ground and cut pieces out of the rails. A signal post was also damaged.

Bomb 7: fell in a chicken run belonging to a Mr. Hudson of The Beacon. Seventeen fowls were killed.

Bomb 8: fell at the bottom of the chicken run making a hole about four feet deep and ten feet in diameter. Twenty feet of brick and stone walling were blown away. The gap in the wall beside the towpath of the River Wey can be seen to this day.

Bomb 9: fell on the east side of the River Wey breaking telephone wires and damaging the riverbank.

Bomb 10: fell about sixty yards on the same side of the river towards Guildford. It brought down a telephone post and wire and killed a swan.

Bombs 11 and 12: fell in Shalford Park – then a nine-hole golf course. One fell on the seventh green and the other about fifty yards away, both making large holes. It’s believed a fragment of the last bomb struck the shutter of Tollgate Cottage on the Shalford Road.

Telephone inquiries were soon coming through to Guildford from Oxford, Reading and other places asking the whereabouts of the Zeppelin.

At the Royal Surrey County Hospital in Farnham Road all the lights were switched off and there was alarm among the civilian patients, while it was later reported that the soldier patients took the visit of the Zeppelin more philosophically, and even joked about it.

A Charles Hodgson who lived at Shamley Green told William Oakley, the then editor of the Surrey Advertiser, that no bombs would have been dropped on Guildford had the Zeppelin not been alerted by the ‘popguns’ firing at it from the Chilworth gunpowder works.

A William Harvey told the Surrey Advertiser that the Zeppelin was quite low when it first appeared over the town, but rose rapidly to a great height after it had dropped the first flare. In the brilliant light of the flare he said he could see the windows of the airship and what he believed to be faces looking out.

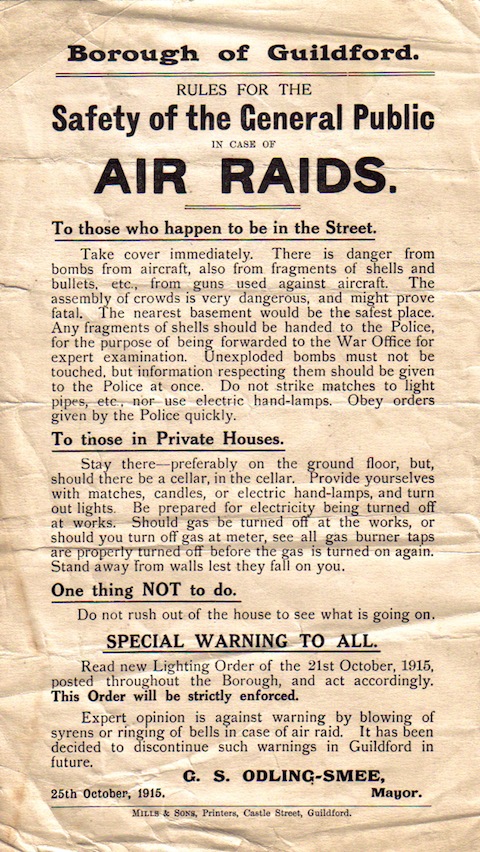

Such was the reporting restrictions in place at the time, none of Guildford’s local newspapers were permitted on reporting the event – it was the biggest story they had probably had in living memory.

In 1983, the then curator of Guildford Museum, Matthew Alexander, interviewed, Ernest Yates, who was born in Guildford in 1906, and who recalled the Zeppelin raid. He said: ‘It was a clear moonlit night and I awoke suddenly to the sound of loud, excited voices, some raised in anger, in the road outside our house.

‘Many families were there clothed in a sketchy fashion, all of them gazing upwards. The cause of all this uproar was the unmistakable shape of a Zeppelin silhouetted in the moonlight like a cigar suspended in space. Its movement appeared slow at such an altitude. Everyone was wondering what might happen, when argument was translated into action. Our next-door neighbour shinned up a lamp-post with the intention of putting out the gaslight. After much puffing and blowing, this burly middle-aged man achieved his object, to the applause of those below.

Tom Parsons, a St Catherine’s resident, remembers shrapnel from the raid being embedded in the boiler house and potting shed building in the south-east corner of St Catherine’s Nursery (where Turnham Close now exists). The shrapnel was still there until the buildings were taken down when Coombs Garage bought it in the 1980s.

A story has passed down the descendants of a Mr Rowlands, who was the landlord of the Anchor and Hope pub. When the raid took place his wife was sitting on the outside toilet. She sat tight as the bombs began to explode until the blast of the fifth bomb, exploding just across the Portsmouth Road, took down the walls of the outhouse leaving the poor woman exposed and terrified!

Blast from what is believed to have been the sixth bomb caused damage to some of the cottages in The Valley breaking tiles and windows. A long-term effect was caused by the collapse of some of the lime plaster ceilings inside several of those cottages.

During the repair work, the collapsed plaster was spread on the shared walkways around the cottages. A former resident, Elsie Oldroyd, used to complain that even after the Second World War her children would walk it into the house when it had been wet outside.

The Chilworth Gunpowder Mills was guarded by a detachment of the 2/5th Battalion of The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. Captain James Ness of No. 3 Supernumerary Company of the Queen’s wrote to the commander in chief, Eastern Command, at Horse Guards in London.

‘I report that at 10.05pm last night an airship was heard approaching, and was shortly discerned at a great height approaching from the east and moving directly over the factory. It moved and made a circle over the factory then continued its journey west. The airship returned to the western boundary then turned again west, and shortly afterwards we heard some ten or twelve explosions in the direction of Guildford. The airship again returned to the factory, flew over the western position and disappeared in a southeasterly direction. As soon as the airship was seen, I ordered all lights out at the factory and work ceased. I at once telephoned the Royal Flying Corps at Farnborough. Later on I tried to telephone elsewhere, but found I could not get through, the wires being down between Chilworth and Guildford [having been destroyed by the explosions]. I sent a messenger by bicycle into Guildford and am pleased to be able to report that nobody had been hurt, although a certain amount of material damage was done. Some of the soldiers guarding the gunpowder works fired their rifles at the airship as did the anti-aircraft detachment that was also stationed there.’

In its official report it seems as if its commander was trying to make out his gunners were unlucky not to have brought the airship down.

Captain James Ness continued: ‘Rapid fire was continued until she was obscured. It is thought that she was hit at least once, as a shower of fire was seen near her. We fired 77 rounds and were much handicapped by having no night tracers nor searchlights.’

A letter written by a Jack Featherstonebaugh of Guildown House two days after the raid, notes that he had just got his mother into bed when the first bomb fell in a garden at the end of his lawn, blowing his windows in.

Evidently, his mother was ‘splendid’ as the bombs fell and the house rocked. He then filled the bath with water and watched what he thought were two Zeppelins passing over his house. There was, only ever one.

He continued his letter explaining where the bombs fell and that his mother then had a ‘heart attack’ – so he gave her a tablet and ‘watched the Zepps on their way home’.

But why bomb Guildford? It has been suggested that the L13’s commander, Heinrich Mathy, knew about the Chilworth Gunpowder Mills and was trying to bomb them.

As previously stated, when the gunners at Chilworth saw the airship that night they opened fire. This would have alerted Mathy and his crew, indicating to them that they were over a target of some importance, and is surely why flares and the twelve bombs were dropped.

However, in his log written shortly after the raid, Mathy reported that he had bombed the waterworks at Hampton on the Thames. It is there almost certain that he was completely lost.

Responses to Terror Zeppelin Raid On Guildford Was 100 Years Ago

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Malcolm Wyatt

October 13, 2015 at 2:45 pm

A fascinating story, nicely told, David. For me, it’s often the stories related to places I know so well that bring home the horrors of war and the fear of living under siege.

Stuart Barnes

October 13, 2015 at 2:51 pm

It is a very interesting story and I suppose could be commemorated. If so I think that the most appropriate location would be somewhere along the river and on or near the towpath. However, it is very difficult to decide on just one spot.

Quite by chance last evening I was running through some old tape recordings that I made a long time ago and one of them (Timewatch) had a full programme on the Zeppelins.

It showed the death of Lt. Mathy including the shape of his body in the earth when he jumped out of his Zeppelin from a great height when it was set on fire, as apparently the air crew were not allowed parachutes.

I wonder if that was where the cartoon cinema makers got the idea in some of their films where they showed the shape of a body in similar circumstances but as a joke.

Angela Gunning

October 13, 2015 at 10:08 pm

I heard the talk by David, Martin and Mike a while back, in St Catherine’s Village Hall. It was a really fascinating talk – well researched with some excellent sound effects.

Most informative and enjoyable.

Ian Castle

October 14, 2015 at 10:31 am

In the article you mention that 53 people were killed in Croydon that night. This is not correct. Total deaths in Croydon were nine – incuding three young brothers.

Martin Williamson

October 22, 2015 at 11:17 pm

There are accounts from boys at Cranleigh School at the time of seeing the Zeppelin pass fairly close over the school.

Robert Jones

November 20, 2015 at 8:50 pm

There are two craters in a sloping field overlooking Guildford Cathedral.The field is between The Mount and the Farnham Road A31.

I used to live in Guildown Road as a boy in the late 1960’s and it was said that these were caused by German bombs.

Could these be from the Zeppelin?

No, the Zepelin bomb impact locations were carefully recorded and described, at the time. They fell in a line from near the top of Guildown Road (before it becomes Upper Guildown Road) eastwards to the Shalford Road (near the junction with Pilgrim’s Way). If the craters are bomb craters I expect they are from the Second World War. My colleague David Rose might be able to confirm. A map of those sites does, I believe, exist. Martin Giles

Jackie Inskip (nee Parker)

October 13, 2021 at 8:27 am

Thank you for this article of great interest to me, a former Guildford resident, born at The Jarvis.

Both my maternal and paternal grandparents lived in Guildford and would have known about this night.

A memorial with information would seem a good idea so that future generations know the damage that the Great War inflicted on the town.

David Rose adds: The story was published in 2015 to mark the centenary of the raid and at the time some of us local historians thought it would be a good idea to raise the idea of a memorial plaque in a public place at St Catherine’s. I had seen one in Edinburgh that recorded a Zeppelin raid there during the First World War and though ‘why not one at Guildford?’. However, no interest has been shown and I fear with the centenary commemorations of the war concluding three years ago now, it would take a great deal of public effort to resurrect the idea.

George Potter

October 14, 2021 at 10:23 am

It might be an idea to write to the county councillor for the area to ask if their members allocation could be used to fund the installation of a commemorative plaque.

Perhaps a useful first port of call would be the St Catherine’s Village Association to see if they could organise finding a location for it?

David Rose replies: Thanks George, some good points, perhaps the association might now come forward on this, or other interested people?

Us local historians already know where we would like the plaque to be placed – on the wall of the house (painted white) that faces the main road through St Catherine’s. At the time of the Zeppelin raid it was a pub named the Anchor and Hope, but sometimes also known as the St Catherine’s Inn. It suffered some damage from one of the bombs.