Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Beekeeper’s Notes June 2016: To Propagate Is The Order Of The Day

Published on: 1 Jun, 2016

Updated on: 6 Jun, 2016

Hugh Coakley keeps bees in Worplesdon. We know about the birds and the bees but do we know how bees increase and propagate? He continues his monthly notes below…

The weather is picking up, nice and warm, mainly dry. There has been blizzards of blossom everywhere and the bees have been taking advantage of the abundance by bringing in pollen and nectar back to the hive.

Coming into land on pear blossom in my garden. She looks already well loaded up with pollen on her back legs but she is still coming in for more. Click on the image to enlarge it.

There are lots of different coloured pollens again. The dark orangey red pollen of the horse chestnut trees which are now in flower is very noticeable on the bees bearing it into the hive and even on the frames inside.

But it is also perfect weather for swarms.

Honey bee queens mate with drones (see Beekeeper’s Notes September ’15) and then return to the hive for a life of egg laying. This act of procreation allows a single hive to maintain itself and continue.

The single colony should raise enough workers to bring in what they need to eat and to nurture their young.

But how do bees propagate? How do they increase from one colony to two, then four and so on?

The answer is that bees swarm.

The old queen leaves the hive with about half of the colony and sets up a new home. Before she goes, the workers feed a small number of eggs in queen cells with excess royal jelly. This triggers the development of queen larvae who, once hatched and mated, will be able to take over from the old, no longer resident, queen.

Queen cells, long, peanut shaped cylinders in which honey bee queens are being developed. (Courtesy of Scientific Beekeeping.com).

So when you see a swarm, you are seeing one colony splitting into two. The bees are increasing the numbers of colonies, giving themselves the chance to spread and reducing the risks of dying out.

The first swarm from a colony is a ‘prime swarm’. If the colony is large enough, the swarming continues with succeeding swarms, known as casts, each getting smaller and smaller.

The worker bees decide when to stop swarming. Once the decision is made, they tear down the walls of any remaining queen cells and kill the queen inside. Grisly but a spare queen in a hive is as useful as a spare bride at a wedding – not useful or welcome.

The photo below is of a queen cell in my apiary from which a queen has emerged.

Queen cell after the queen has emerged. Click on the photo to enlarge it in a new window. You can see the trap door hanging beneath the cell where the new queen has crawled out. Next to it is another queen cell where the workers have torn down the sides of the cell. They have decided that swarming is now off their agenda.

Darwin had trouble fitting bee behaviour into his evolution theory. Why would sterile worker bees slave away for the colony and even die in its defence if they couldn’t pass on their genes?

It makes a bit more sense if we see the colony as a single entity, not as individuals bees working separately. The swarm is an example of this. They are passing on their genes through their mother, the queen.

It’s not about individuals but the survival and growth of the colony that counts.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

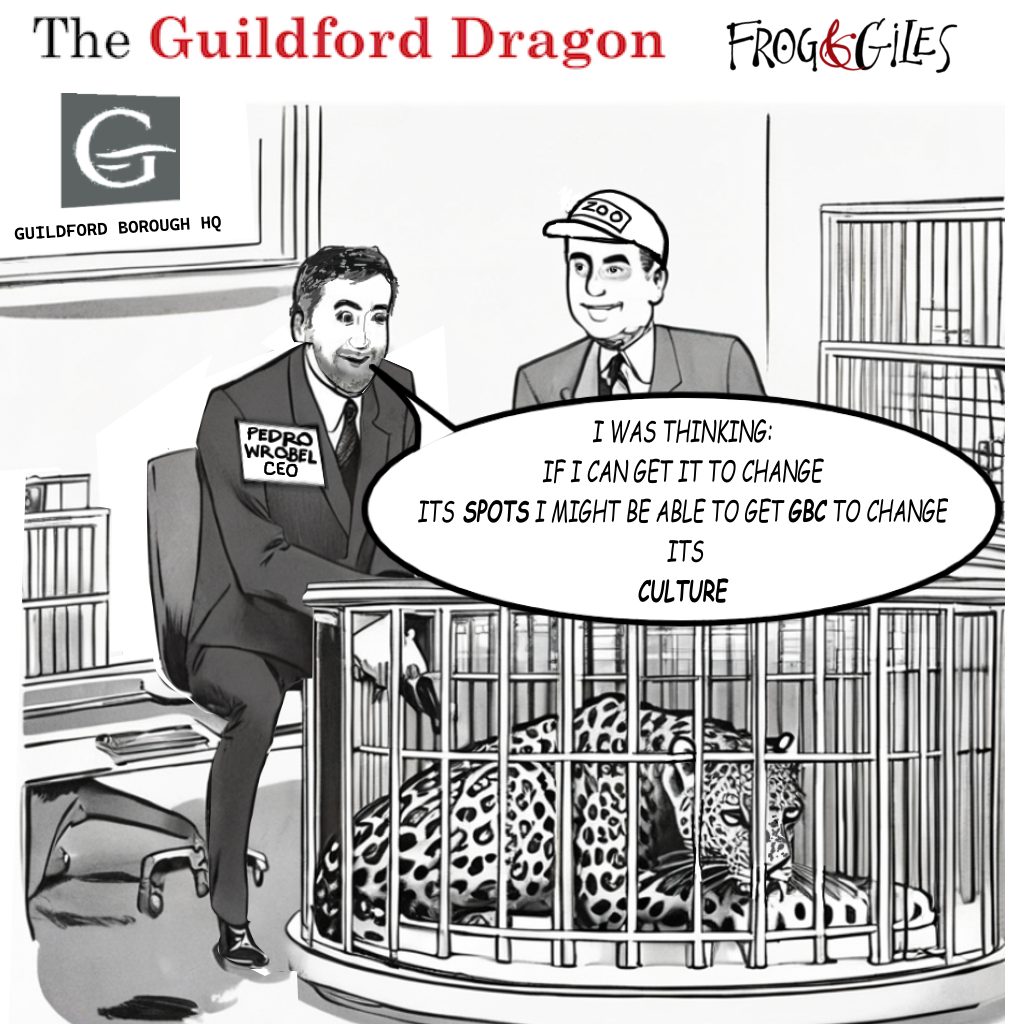

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments