Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

My Direct Family Link With The Great War

Published on: 6 Aug, 2014

Updated on: 16 Sep, 2014

By Martin Giles

A hundred years seems like a long time. Few of us live that long and given that we can remember little of our first few years the memories of even the longest lived rarely span a whole century.

So now there is no one around who can really tell us what it was like to be alive at the outbreak of the First World War. But luckily we have plenty of archive material, both contemporary written accounts or filmed interviews recorded before the generation involved died.

Some of us of who are now older might have their own memories of talking to a relative about their Great War experience. I do.

My mother was a shopkeeper, so worked on Saturdays but closed the shop as normal from 1pm to 2pm for lunch which we would all have at my grandparents’ house, very close by in Mytchett.

The talk around the table was most often on the topics of the day but frequently, too, about history and their experience of it. My grandparents were of the generation that lived through two world wars, so there was a lot to recount.

My great-grandmother lived with my grandparents. She was quite a character, smoked Woodbines, drank brown ale and liked to bet on the horses. In short, interesting company for a young lad. I think I must have regarded her as a living museum piece but one that would dispense beery kisses.

Despite the beer, she seemed to lack any sense of humour and recounted, on more than one occasion, with feeling, how annoyed she was with herself for having waved at the Kaiser during one of his visits to England. Even aged about seven I thought that she was a bit hard on herself. After all, I didn’t suppose it had had a great historical impact. She also spoke hatefully about Zeppelins. She made it sound personal.

I spoke much more frequently about the past to my grandfather who, being born in December 1899, was as old as the century. He was one of thousands who joined up under age, spurred on, we learned after his death, from his sister (my great aunt) by receiving a white feather in the post when he was sixteen.

I think I must have always been interested in hearing his stories and I suspect he sensed a willing audience. As my father (who probably had a much more intense combat experience soldiering from 1939 right through to 1945) died when I was young, I spent a lot of time with my grandfather.

He was a very good grandfather to me, we got on well and when we found ourselves killing time, waiting for my grandmother to return to their car (an Austin Somerset which he called the “Grey Lady”) from some shopping trip, he would often talk about his life. Looking back, I think he was keen to pass his story on.

When it came to the First World War he told me that when he decided to leave his job, I think as a clerk in a solicitor’s office, and join up, he was worried that if he enlisted in his home town, Dorking, someone might recognise him and know that he was under age. So he caught the train to London and enlisted there, which is why, most likely, he joined the Kings Royal Rifle Corps instead of The Queen’s.

Anyway he succeeded and underwent basic training at Blackdown. He told me about this once parked up near some army huts in the camp near the crossroads. In those days before the IRA mainland bombing campaign, army camps were open. He was still able to point out some of the huts that had been there during this period.

He talked of how hard some of the training had been – forced marches with unbroken boots, blistered feet while carrying the unfamiliar burden of full service marching order. But like most old soldiers he talked about his experience with pride; the training might have been tough but he had been able to take it.

He was also selected to form a guard when King George V visited the camp arriving by train, perhaps to open the station. The railway was decommissioned in 1921 but the old wooden chalet-style station, near “The Triangle” at the southern end of Deepcut Bridge Road was still there in the 1960s and had become a museum.

My grandfather took me there one day and thought he recognised himself in some of the photos on display of the King’s visit. I wonder if copies still exist?

While he was still being trained, a concerned aunt wrote to his commanding officer. She informed him that her nephew, Cyril Hector Hutchings, was not old enough for army service, or at least for active service. The CO replied thanking her and saying that my grandfather would not now be sent with the next draft to France but instead, as he was nearly old enough, be transferred to the Army Service Corps.

I don’t recall if my grandfather said this was a disappointment but it must have reduced his chances of being killed or wounded, considerably.

Neither do I remember him saying much about the transfer or the training he received or where he received it, but he did end up on the Western Front, eventually, as a motorcycle despatch rider.

I have read recently that all despatch riders were promoted to full corporal as they had to be able to speak to the officers! I wonder if that is true. Was it unthinkable for a private soldier to be able to converse with an officer? Of course, social and rank divisions were much stricter in those days.

I remember him saying that he got to know the roads in the sector behind Arras (which he pronounced as written, not the French way) and Douai (which he pronounced Do-eye) very well. He told me that he once came across a dead horse that had been blown up into a tree and on another occasion a bridge he had crossed had been destroyed by shellfire before he could return over it.

To him, a young lad that volunteered under age, even though the horrendous losses were already well known, it was not an unnecessary war. Even in the 1960s when it was fashionable to think the First World War was entirely futile, as some still do today, he felt that German aggression and expansion had had to be stood up to and stopped, simple as that.

At the end of the war he decided to stay in the army and underwent training as a motor mechanic. He was sent to Egypt and became the MT staff sergeant in a oasis settlement called Siwa, only leaving the army reluctantly a few years later because his widowed mother wanted him to return home.

When I was a boy playing soldiers, I would wear his black KRRC cap badge (there was an ASC one too but even then I preferred the infantry) and his two Great War medals. Sadly, I have lost them over the years. We never value such things enough.

I wish I had asked him more about his time as a soldier and I wish I could recall more of our conversations. We never find out enough about our living relatives. But I think myself lucky to have the memories I do have of him telling me what I have shared with you. It is my direct link with that terrible time and together with my own army service makes the current commemorations so much more meaningful.

Do you have memories of talking to a member of your family who remembered the Great War? Why not use the ‘Leave a Reply” feature below to share them?

Responses to My Direct Family Link With The Great War

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

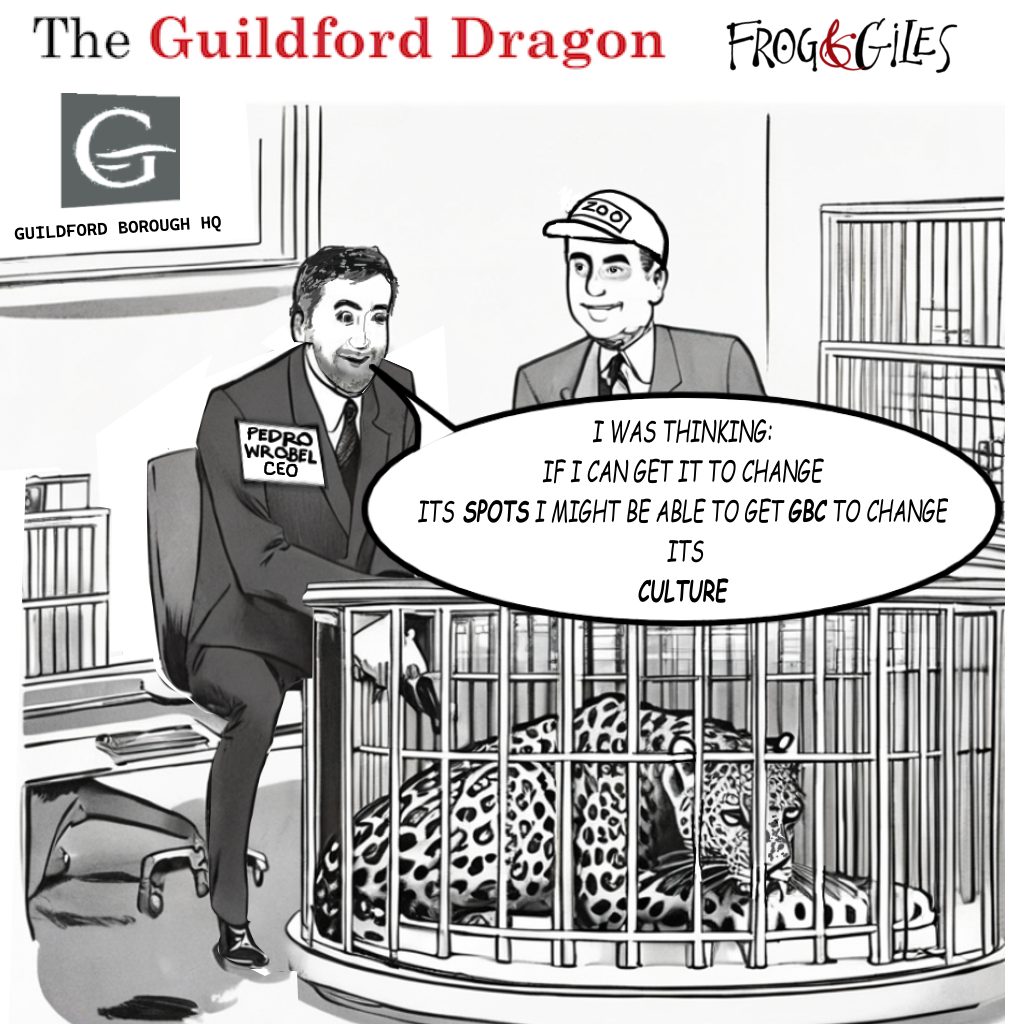

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Bernard Parke

August 7, 2014 at 10:11 am

Like many of these young conscripts who were drawn into the privations of the Great War Pte. Robinson a Lewis Gunner of The Devonshire Regiment would not speak freely in later years of its horrors.

He was at the tender age of eighteen when after a short church service at Horsell found himself in the trenches in France.

Soon after arriving he was detailed to go forward from the front line into no man’s land into one of the many shell holes as a forward lookout. He was in the care of seasoned soldier, known in the army as “old sweat”.

When Pte Robinson asked what were they expected to do the reply was:”Well lad, I don’t know what you are going to do but I am going to have a kip.”

He also told of rats the size of cats gorging on the dead horses and men. They even attacked sleeping men.

On one occasion the sergeant said to his platoon: “You lads look tired, why not go on sick parade for some R & R.”

Taking this advice Pte Robinson and his mates went to the M.O. His conclusion was was Medicine and Duty.

He said “Okay lads you are not sick. I should prescribe just duty.”

Such a statement would have meant the firing squad which of course the senior NCO was well aware of.

An example of how this Great War with its victims had sunk to the depth of depravity.

Pte Robinson was eventually invalided out of the front line and returned to “Blighty” where he and others were billeted in flimsy huts on Salisbury Plain.

He said that in the depth of winter more of his colleagues died of hypothermia than at the front from wounds they received fighting for king and country”.

How life has changed but at such a price for those that gave all for what?

Eddie Robinson who was engaged to my Aunt for nearly sixty years. He lived with her at The Connaught Café built by my maternal grandfather, a veteran of the Boer War in which he serves through the whole campaign in The ranks of The Scots Guards leaving my Aunt and her my Grand Mother here in England.

H.E. Robinson ran his surgical boot making business from Boundary Lane in Woking on NHS contract serving hospital throughout the south east.

He also made shoes for a member of the Royal Family and became President of the Woking Chamber of Commerce and was and active member of the Rotary Club.

When I asked him why he did not go into local politics he said that he could stand such petty behaviour especially after those years in the trenches.

Martin Giles

August 7, 2014 at 10:23 am

It’s a small world.

My grandfather, the subject of the article, must have lived next door to Eddie Robinson after he had bought and ran Brookwood Post Office, next door, in the early 1950s. (My mother ran the Post Office counter within the shop.)

Grandfather also required surgical shoes after a car accident at the end of the war (caused by a Canadian soldier driving on the wrong side of the road) and I can remember going to Woking with him to collect them. Presumably this would have been from H.E.Robinson. I seem to remember that we parked near, what was, Woking bus station so perhaps the workshop was near there?