Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Doctors, Surgeons and Apothecaries in Guildford 1600-1800

Published on: 12 Dec, 2023

Updated on: 12 Dec, 2023

By Mary Alexander

There were three main branches of medicine in this period covered from 1600 to 1800.

Doctors of physics diagnosed ailments and prescribed medicines, apothecaries made up the medicines, and surgeons did surgery, as today.

In practice, the situation was more fluid. Although most of the 42 medics I have found were described as one of the three, Alexander Hallamby, active in the mid-1700s was a surgeon and apothecary, and John Howard, who died in 1755 was a surgeon and man-midwife.

William Newland, in the late 1700s was an apothecary, surgeon and man-midwife, though he seems to have acted as a GP.

A man-midwife was simply a male medic who attended births. The role was so strongly identified with women that no-one could think of another name for them at this period.

The medics described here were professional men who relieved the sick for payment. They were independent, working for themselves, though the parish overseers of the poor paid them to attend paupers when necessary.

They were men of good standing in the community who played their part in civic and parish life, witnessed wills and acted as trustees. They often came to Guildford from outside.

Doctors usually had degrees, while the others were apprenticed. Alexander Hallamby took at least three apprentices who then went elsewhere to work. Caleb Woodyer from Petworth was apprenticed to William Newland as a surgeon. Woodyer stayed in Guildford, and his son Henry became a well-known architect.

The overseers of the poor mostly paid ordinary people (perhaps other paupers) to look after the sick. In 1700 widow Jones was paid for looking after Stephen Weeks for 28 weeks, and Thomas Eveston was paid for helping him to and from bed. In 1786 a surgeon examined a lame boy and in 1791 a man was bled by a doctor.

Early surgeons were called barber-surgeons but as surgical knowledge increased the surgeons formed their own college, in 1745.

Watercolour painting of Guildford’s Abbot’s Hospital.

Two Guildford barber-surgeons were Henry Horner, who became Master of Abbot’s Hospital when he retired in 1644, and John Staples who died in 1675.

The earliest record of a Guildford surgeon is in Elizabeth I’s reign. Thomas Bentley was asked by Sir William More of Loseley, a JP, to say whether a certain John Baker would recover from his wounds, as part of an investigation. Bentley thought that he would.

All the medics seem to have been well-off. They invested in property, and later in bank stocks.

The Tun Inn and cornmarket.

Richard Huggett, a surgeon, inherited the Tun Inn in 1719 and enlarged it. He could expect a good income from it because it was opposite the Guildhall and housed the Cornmarket.

John Cunningham, a surgeon, owned the Ship Inn (just downhill from Holy Trinity church) and other property in the parish.

Richard Hallamby, probably the brother of Alexander, had enough money to leave £500 to his servant Fanny in 1787.

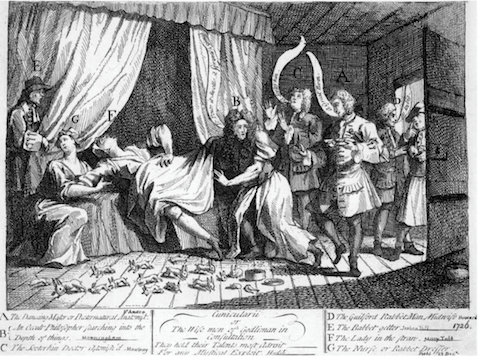

William Hogarth’s illustration of Mary Tofts, the Rabbit Woman of Godalming.

Brothers John and Thomas Howard were surgeons in the early 18th century. John got involved in the case of the Rabbit Woman of Godalming in 1726, and despite being a surgeon and man-midwife appeared to believe that she gave birth to rabbits.

He must have lived it down because his house was noted on a map of Guildford in 1739, as one of the important men in the town.

Doctors of physic could be very wealthy, probably because they came from families who could afford to send them to university.

Swithin Adee was born in Devizes in 1704. He married Olive Child of a wealthy Guildford family and inherited land in Effingham through her.

He also owned a house in London and eventually moved to Oxford. He was a Fellow of the College of Physicians and of the Royal Society.

Doctors Daniel and James Bissell, active from about 1650, were probably brothers.

Their sister died in 1685 and her will shows that she owned the latest in fashionable furniture such as “a great looking-glass” and a chest of drawers.

Number 49 Quarry Street.

Dr Robert Mitchell came from Dumfries. He lived at 49 Quarry Street (once Traylen’s bookshop) and re-fronted it with an elegant brick façade.

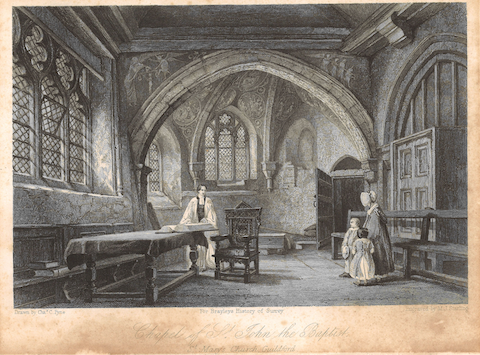

St Mary’s Church, illustration of its Chapel of St John the Baptist.

His will of 1771 mentions jewels, silver plate, books, carriages and horses and two sets of portraits of himself and his wife. He and his wives were buried in the chancel of St. Mary’s – a sign of high status.

Apothecary John Harraden was apprenticed to his father Richard in 1717, but Richard died the next year and his wife continued their son’s training.

This suggests they were closer to tradesmen than the doctors, with husband and wife running a business, though both Richard and John were called “Mr” in the burial register which shows high status.

The Shaw family included a dynasty of at least six generations of apothecaries. The first was William, mentioned in 1599, who died in 1647 leaving his son Samuel the lease of his house and his physic pots and boxes.

Samuel was followed by four Williams, who all owned property in Guildford and elsewhere. The last one died unmarried in 1828 aged 80.

He described himself as a gentleman in his will and had probably given up being an apothecary many years before.

Shaw family tomb (foreground), Holy Trinity churchyard.

He rebuilt the family tomb which can still be seen in Holy Trinity churchyard near the gate by the parish hall. Very unusually, it commemorates burials going back to 1562, but is very difficult to read now.

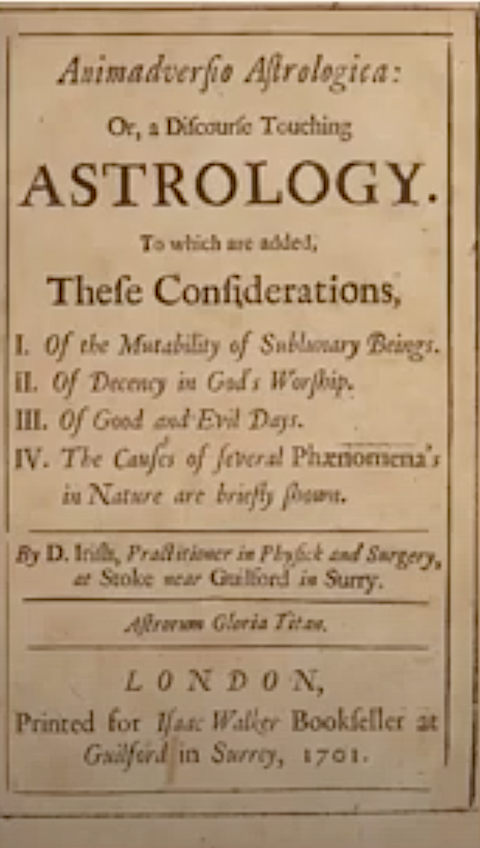

A particularly interesting doctor is David Irish. He wrote a book in 1700 with advice about medicine and an account of his own remedies.

The Red Lion Inn, High Street, on the corner of Market Street.

He called himself a doctor and surgeon and said that his remedies could be got from his house or at the Red Lion Inn on market days. (Market Street was once the inn yard of the Red Lion.)

He was at his house in Thorpe on Tuesdays and at the Swan in Chertsey on Wednesdays.

A document survives in which he agreed to treat the wife of a man from Witley of “hypochondriac melancholy madness”.

He would have taken her into his house in Leapale Lane (earlier called Madhouse Lane) to treat her.

Judging from his writing, the treatment would have been kindly and sympathetic.

One of David Irish’s publications, this one on the subject of astrology.

The private hospital survived well into Victorian times, when there began to be more state involvement in all types of health care.

Doctors were still independent professionals after 1800 but were also more likely to be employed in institutions such as hospitals and workhouses.

Picture postcard from the early 20th century captioned Archbishop Abbot’s School, and as seen from North Street. It shows the cloth hall building and also the building that had been used as a workhouse at one time. David Rose collection.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments