Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Dragon Interview: Council’s Complaints Process Is ‘Not Fit For Purpose’ Pt 2 – How Do We Fix It?

Published on: 3 Feb, 2023

Updated on: 5 Feb, 2023

It is rare to get an insider’s objective view of the borough council so we should really value this contribution from Bernard Quoroll, a retired solicitor living in Guildford, who was a senior figure in six local authorities.

It is rare to get an insider’s objective view of the borough council so we should really value this contribution from Bernard Quoroll, a retired solicitor living in Guildford, who was a senior figure in six local authorities.

See Part One of this interview, Council’s Complaints Process Is ‘Not Fit For Purpose’ – Says Retired Chief Exec, here.

Quoroll speaks of what he found as someone who was part of the complaints process for some considerable time and shines a spotlight on the behaviour of councillors and council officials. His conclusion is that the process does not serve democracy well but he also explains why.

He also gives forthright answers to a series of questions that are vital in any discussions about local democracy and how the problems can be addressed. Those of us who care how it works, or doesn’t, should read on…

Part 2 – The solution?

Interview conducted by Martin Giles

How could the process be improved?

I think the starting point is that no government is likely to revert to the old national system, even a reformed one. Doing so would be contrary to a decades-long process at national and local level of removing restrictions on the activities of elected people in substitution for mechanisms previously used to secure greater probity in public life. This is a very concerning trend which has been justified on grounds that have little to do with probity. It is however a very large topic and is perhaps outside the range of your questions.

Anyone interested in it might want to read a report by Transparency International UK as long ago as 2013, called “Transparency in UK Local Government: The Mounting Risks”, which gives more background.

A more realistic alternative would be to operate the complaints procedure outside individual councils but still locally. This could be done by adopting a consortium or joint management approach which is now commonplace in local government. It seems to me that such an approach could be adopted within existing budgetary constraints.

It would drive the adoption of a single complaints handling procedure and code of behaviour which could adopt best practice from all the councils within the county area or even further afield. For example, Guildford Borough Council’s code, which is legally compliant, is currently three times the length of the one adopted by Surrey County Council.

This approach would remove internal self-adjudication entirely from individual councils and provoke re-examination of every element of the various codes in operation, the main defects of which I have already touched upon in my answers to earlier questions, but there are others needing re-examination.

Doing so would improve consistency, substantially remove or reduce the problems created by some of the defects I have mentioned and allow for the development of more sophisticated, less adversarial dispute resolution procedures, such as mediation.

Done properly it could provide a substantial boost to public confidence in complaints handling and therefore in the legitimacy of locally elected councils.

It would of course require political courage for locally elected people to say that they no longer want to follow a centrally driven trend toward internal self-adjudication and protectionism. I am not sure that I should hold my breath while that happens!

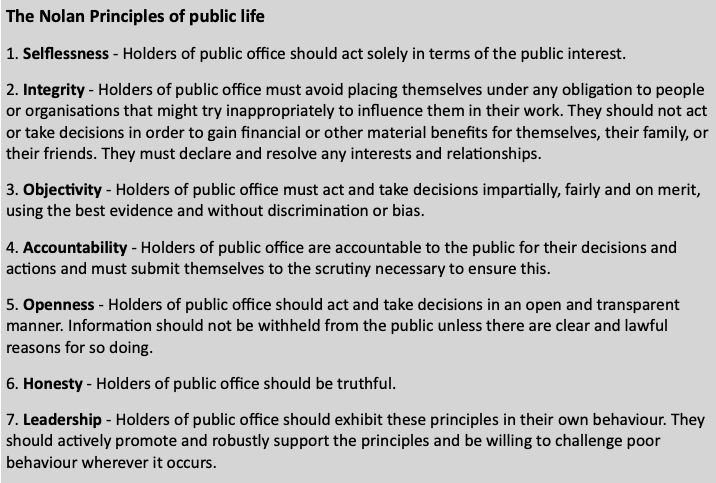

7. Do councillors and council officers keep the Nolan Principles in mind all the time in their work?

I don’t think any councillor seeks election, or any officer comes to work, in order to feather their own nests or to do a bad job. But I may be a bit naive in that because there have been some egregious examples of bad behaviour in the past, which have scarred local government’s reputation.

I have to say however that no one now really knows the answer to that question because the Audit Commission and Standards for England, which kept scores, were abolished by central government some years ago.

I have to say however that no one now really knows the answer to that question because the Audit Commission and Standards for England, which kept scores, were abolished by central government some years ago.

Nor do I think that councillors and officers leap out of bed reciting the Nolan Principles as their mantra before beginning the day’s work. A newly-elected councillor will typically get an evening’s training session on the complaints code, including Nolan, among many other training sessions on offer, shortly after an election. (Old hands may not bother to turn up for a repeat of training sessions which they have already attended albeit four years earlier).

Beyond that, there will be occasional references to the Nolan Principles in documents and agendas where they are relevant. After all, the Nolan Principles are only common sense aren’t they?

But perhaps the question misses something more fundamental in relation to people who decide to seek election and the public who vote for them.

Nor do I think that councillors and officers leap out of bed reciting the Nolan Principles as their mantra…”

Nolan’s principles – selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership – describe behaviours that few of us, elected or not, always observe in our daily lives. Why should we expect the people we elect to be any better than we are?

The answer seems to be because they ask us to put our trust in them.

At the national level, we do seem to accept that we elect people knowing that they will sometimes have to do things which we would regard as immoral. We seem to make a distinction in between the big national issues of the day (most obviously foreign policy) and the personal behaviour of individuals in office.

We also know that adversarial, tribal politics is sometimes as damaging to the lives of politicians as it is to the people who vote for them.

At a local level, the pressures are less intense but the game of politics seems to be becoming more tribal and more adversarial. Does it need to be that way? When you look at complaints made against politicians, it is becoming harder to distinguish bad behaviour from what we expect politicians to do. The balance between people who just want to get elected to do some good in their own communities and those who want to pursue national political objectives at local level seems to be changing too.

…adversarial, tribal politics is sometimes as damaging to the lives of politicians as it is to the people”

I am not so naive as to expect local politics to be replaced overnight, or at all, by bland cooperation. Politics is part of life. We get the politicians we deserve and real naivety rests in the proposition that politicians are somehow a different tribe of people. Better decisions do seem to come from challenge, negotiation and compromise rather than from single-minded political dogmatism.

My proposition is rather that local politicians owe it to themselves and to their electors to engage with each other from time to time to debate what kind of council they really want to be and to maintain that dialogue over time.

Having a legally compliant complaints procedure does not come close to helping councillors immersed in the heat of political battle to think harder about what they have in common locally, rather than generating short-term propositions designed to get them elected. The best time to start doing that is in the immediate aftermath of an election.

8. Are there other even more fundamental problems to address?

8. Are there other even more fundamental problems to address?

One reason why I decided to spend a couple of years thinking about integrity in public life was a growing concern throughout my career that central and local government was losing the trust and confidence of the voting public.

Having an effective and trustworthy local complaints procedure is only a very small part of that concern.

At local level, there has been a wide range of initiatives over many years, mostly led from the centre, which seems to illustrate a desire to recreate local government in its own image and which in turn are reducing faith in local government. A claim of localising has not in practice been matched by meaningful actions when you look at the bigger picture. The cumulative effect has been to accelerate a downward trend in public belief and confidence.

Very few councils use their complaints procedure as a means of learning about how they might need to change…”

This may not make exciting bedtime reading but it is important.

Good governance requires both rules and integrity, alongside the other Nolan Principles. An effective complaints procedure provides one small window into whether a council is becoming politically or managerially toxic.

Having a legally compliant complaints procedure is conflated by many councils with meeting its public obligations to govern with integrity. It also provides an opportunity for those in leadership positions to distance themselves from what may be happening in their own councils.

Very few councils use their complaints procedure as a means of learning about how they might need to change and remarkably few show much informed curiosity about why their reputation is suffering.

That is hardly surprising. Politicians usually want to get elected to “do things” in a hurry in their local communities. Their priorities are sadly too often short-term and they are by nature and role reluctant to engage, even privately, in what might be regarded as navel-gazing. It opens too many cans of worms.

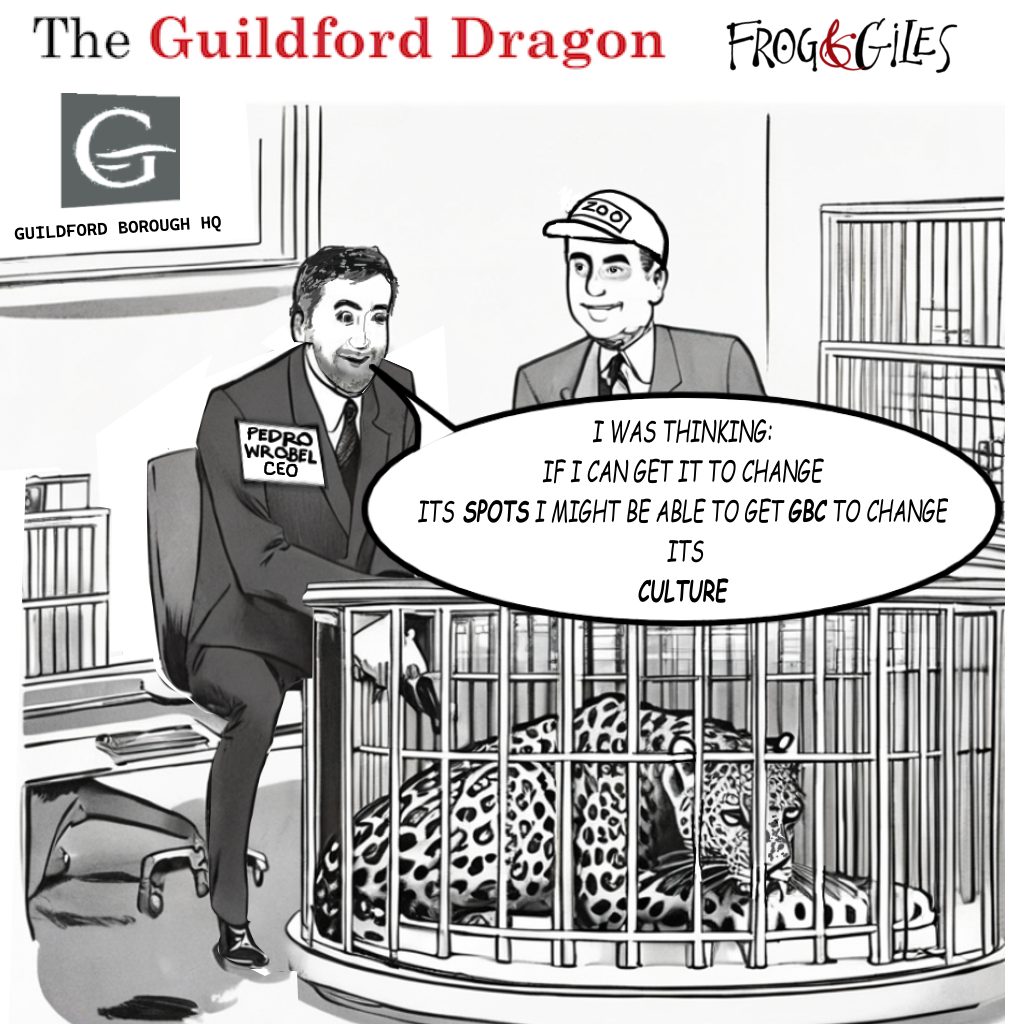

Even fewer chief executives, who are trying to keep the local ship of state afloat with plummeting resources and a raft of pressing demands, want to say to their leaders that quality time needs to be set aside for considering what governing with integrity means, how to get reliable ways of assessing where change is needed and what then needs to be done to make it happen.

I have had that discussion several times with chiefs and leaders. No one has ever suggested to me that my thesis is wrong but there is always a reason why they just have to do something else first.

Good governance or acting with integrity comes from the very top of local authorities both politically and managerially. It is one of a small number of key organisational values which need to be embedded in everything a council does, if it is to grow in legitimacy with the voting public.

It begins with a genuine curiosity about how the council is perceived and a recognition that perceptions are important. It requires a clinical search for evidence which is not tainted by group think and thoughtful consideration about how to introduce any changes that need to happen.

No one has ever suggested to me that my thesis is wrong…”

It puts a spotlight on political and managerial behaviour and is uncomfortable to live with but does not seek to suppress political difference. It needs to be lived at every level and in every aspect of organisational life, not just printed on publicity material.

Achieving all that requires commitment, reinforcement and an openness to learning from employees, opposition parties and many others, not least the public it serves. It is hard to secure and easily lost, especially in complacent councils that conflate form filling with excellence. It is much more than an attitude of mind. It needs hard-edged practices and routines.

In short, acting with integrity is in my view a, if not the, key ingredient for any organisation which claims the right to govern. Alongside that, worries about complaints procedures are a bit of a sideshow.

9. What part can the media play in this process?

9. What part can the media play in this process?

The media plays an important role in holding councils to account and hopefully, in explaining to the public more sides of any given story. They see the world from a different angle than officials or elected people. Good reporters know how to dig and can give a voice to people with different perspectives.

It isn’t all good news with the media of course. They can be intrusive and unfair, and their appetite for intimate detail can be damaging to individuals.

Sometimes, the personal circumstances of individuals, even elected people who give their time voluntarily, do deserve to be respected.

But anyone who decides to engage in public life may have to accept that, within limits, their actions will be scrutinised. Done well, it illustrates a healthy democracy, even though there are times when it can feel too much like a “body contact sport”.

Editors of course have a responsibility to get the balance right.

See more articles relating to council complaints here.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments