Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

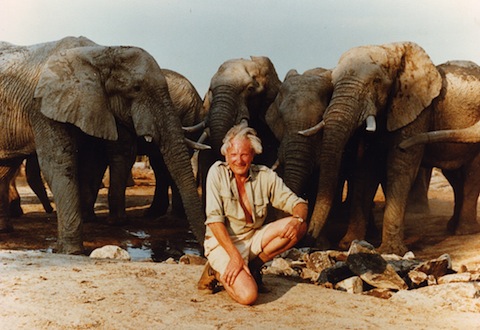

Exclusive: Artist David Shepherd’s Amazing Contribution To Wildlife Conservation

Published on: 27 Mar, 2014

Updated on: 31 Mar, 2014

Renowned artist, conservationist and lover of steam engines, David Shepherd CBE, talks exclusively to Dani Maimone about his life and work.

David Shepherd CBE is an extraordinary man. Not just an internationally renowned wildlife artist whose paintings often sell for up to £30,000 each but a passionate conservationist who founded a small but powerful charity in 1984.

The David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation, located in Shalford above the foundation’s shop and art gallery, raises money and awareness to help save endangered species, including elephants, rhino, tigers and snow leopards. In the words of the foundation’s CEO, Sally Case: “We may be small but we pack a punch.”

Now in its 30th year, the foundation has gone from strength to strength, raising hundreds of thousands of pounds for conservation projects and notching up some impressive successes.

Anti-poaching and park protection are the main areas the charity has been very involved with. In 1960 a dramatic incident prompted David to set up the charity all those years ago. He came across a waterhole poisoned by poachers with more than 200 zebra lying dead around it. He realised then that he could sell his paintings, already in great demand, to help pay for wildlife conservation and give something back to the animals that were bringing him such great success as an artist.

David was born on April 25th 1931 in Hendon, in his words: “A stone’s throw away from what is now Brent Cross Shopping Centre.” He developed a love of aviation at a young age, inspired by the many amazing aircraft he saw flying overhead on their way to air raids during the war. He was unaware of the seriousness of their journeys. Rather poignantly, he sold his first wildlife painting to the RAF in Nairobi some years later for the meager sum of £25. He recently sold a tiger painting at a charity auction for the foundation for £30,000, a true measure of the success he has achieved with his work.

As we sit together in his office above the gallery in Shalford, David tells me about his early days and the fact he was such a terrible artist that the Slade School of Fine Art in London rejected him, a notion I find hard to believe.

Looking around the gallery and seeing the amazing works of art that he has produced and that have earned him world – wide acclaim. He says: “My life was a total disaster until I was 20 years old. I wanted to be a game warden in Kenya. So, after my education I rushed off to Kenya with the incredibly arrogant idea that I was God’s gift to national parks. It was a disaster. I was told I wasn’t wanted. My life was in ruins. That was the end of my career in three seconds flat.

“Up to that point my only interest in art had been to escape the rugger field at school. I fled to the art department and painted the most unspeakably awful painting of birds.”

He tells me he still takes the painting to talks and lectures as proof of how bad he was when he first started out as an artist.

He returned to the UK deflated, with the option of becoming a bus driver or training as an artist. His father encouraged him to seek some artistic training but as the Slade had rejected him saying that he had no artistic talent and wasn’t worth teaching, the bus driving option looked increasingly promising.

It is now that David brings up the name of his mentor, Robin Goodwin, a professional artist specialising in portraits and marine subjects. It was a fortuitous chance meeting at a party that changed David’s life forever and he speaks of Robin with a great fondness in his voice.

“He took me on, saying, it’ll be hell because you are so bad, it’ll be a challenge. He only once had anything good to say to me over the whole three years I trained with him, but we had tremendous fun. He also taught me to take it seriously as a business, telling me to paint every day and reach out to the world as the world will not come to you.”

After completing his training with Robin, David’s first job was as the Heathrow artist taking bus tours around the airport painting airplanes. The RAF spotted his work and in 1960 invited him to Kenya as their guest.

“They didn’t want paintings of aircraft.” David adds: “They asked me if I painted animals. I had never painted an animal in my life, not even a gerbil!”

His first wildlife painting for the RAF was that of a rhino chasing an aircraft off the runway and the rest, as they say, is history.

He says: “My career took off and I’ve never looked back.”

David has been married to the lovely Avril for many years and they have four amazing daughters, one of whom, Mandy, is a successful wildlife artist in her own right as is his granddaughter Emily. Naturally, he is very proud of them but adds: “I’m still here.”

He certainly is and continues to live life at a rapid pace. “There’s never a dull moment,” he adds, “Just ask my wife.” I don’t doubt it for a second.

As well as wildlife conservation, David also has a passion for steam locomotives, something that developed on family holidays in the 1930s. He was appalled at the way these magnificent machines were being scrapped in the 1960s to make way for diesel.

He continues: “In 1967 after a sell out show in New York I returned to my hotel room in a state of euphoria and before I knew it I was on the phone to British Rail asking to buy a steam engine. It was then I bought Black Prince [a BR standard class 9F locomotive] for a mere £3,000 at scrap value.” He calls her his beloved fifth daughter, as she is very much a part of the family.

He went on to form the East Somerset Railway at Cranmore in Somerset, a registered charity and fully operational steam railway opened by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands in 1975 with proceeds supporting wildlife conservation. It’s the ultimate in boys’ toys and he has been preserving and playing with steam locomotives ever since.

He tells me casually about a conversation he had with Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, himself a keen conservationist. “We are raping the planet David,” said Armstrong, “it’s true,” says David, “We’re all in this mess together and every living thing has a right to be part of the balance of nature. Who knows what our children will see in 80 years time, it’s very sad.”

What message would he pass on to the next generation? “Get the teachers to buy a mirror and ask the children to hold it up to their faces and say, you are now looking at the most dangerous animal on earth.” He has a valid point and one many of us have known for years.

In 2011 David launched his most ambitious wildlife campaign so far, TigerTime, aimed at saving this critically endangered species in the wild. It has a huge celebrity following and has made great strides in supporting vital tiger conservation projects in India, Russia and Thailand.

I ask him what I consider to be an impossible question to answer for a man of his achievements: out of everything that you have ever done throughout the years what would be the main highlight? He replies: “It’s an easy answer, meeting Robin Goodwin, without him I wouldn’t be here today doing what I am doing now and you would be interviewing me on a number 97 bus.”

It’s hard to try and encapsulate the magnitude of the man and his amazing contribution to wildlife conservation in just a few words. The world would have been a poorer place if David Shepherd’s career had taken a different route on a 97 bus and a chance meeting with the artist Robin Goodwin had never taken place. Imagine that!

To find out more about the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation visit the website at www.davidshepherd.org or www.tigertime.info or call the office at 01483 272323.

Responses to Exclusive: Artist David Shepherd’s Amazing Contribution To Wildlife Conservation

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Mark Parris

April 5, 2014 at 8:38 pm

What an amazing man! Thank you for doing so much for wildlife.