Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Letter: Electric Vehicles Are Not The Way To Go

Published on: 6 Sep, 2017

Updated on: 8 Sep, 2017

I totally disagree with G Basnett’s views on electric vehicles, as expressed in his letter: Use of Onslow Park & Ride and Electric Vehicles Needs More Encouragement.

The electricity we use comes from polluting power stations, more of which are, in any case, needed to meet increasing domestic demand before we add vehicles to the equation.

Furthermore, a 2017 report shows that battery manufacturing leads to high CO2 emissions. For each kilowatt-hour storage capacity in the battery, emissions of 150 to 200 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent have been generated in manufacture. The

The Nissan Leaf has a battery pack of approximately 30 kWh. By the time one has been bought, CO2 emissions of approximately 5.3 tonnes have been released. About half of the emissions occur during the production of raw materials and half during the production of the battery in the factory.

You need to drive a petrol or diesel car for 2.7 years before it has released as much carbon dioxide as a Nissan Leaf battery. And, of course, electric cars cannot claim to be “emissions free” when they are powered from an energy grid supplied by power stations burning coal or gas.

Nuclear energy is a solution that now appears to be becoming unaffordable and probably no longer politically correct; EDF’s technical problems with the Hinckley Point power station are a long way from being solved. We are being encouraged to cover the country with windmills, but of course this could mean only driving on windy days (or when the wind’s not blowing too hard!).

And once the petrol tax revenues (£5.5 billion road tax and £27.6 billion fuel duty starts to disappear (2016 figures)) plummet where do you think HMG will look to replace it? Yes, you guessed, taxing electricity more.

The most popular electric vehicle in the UK is the Nissan Leaf. Battery leasing costs are between £55 and £75 a month. The cost of replacing a pack if it’s not on a lease arrangement ranges starts at around £4,920. As far as the guarantee goes, within the warranty period and under their terms and conditions, Nissan are only obliged to repair/replace the modules at the 8 bar point.

A drop to 8 bars will give you around 50 miles range, and only then will Nissan repair or replace, under warranty. Under the warranty Nissan will only repair/replace/restore the modules up to the 9th bar; not replace a whole new battery pack to achieve a full 100% charge at 12 bars.

The constant velocity transmission is about £4,000 to replace, and there are reports that it is prone to failure; probably something to do with the high torque from electric motors.

The second-hand market will be a whole different bag of worms. Cheap secondhand electric vehicles are likely to be out of warranty. Potential buyers need to consider the cost of a domestic wall-box charger, about £350 for a 7kWh unit; government grants are not applicable on purchases of second-hand electric vehicles. Leasing the battery for a second-hand Nissan Leaf will cost about £90 per month for 12,000 miles a year.

I would advise others not to get suckered into the “another diesel is the way to go” blurb. A far better answer is hydrogen and as Cobham Service already has a charging point it’s very convenient for Guildfordians.

Responses to Letter: Electric Vehicles Are Not The Way To Go

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.Recent Articles

- Letter: House of Fraser’s Closure Was the Last Straw

- Letter: The Rights of One Group Should Not Usurp The Rights of Another

- Suspected Fox Poisonings Shock Guildford Resident: Police and RSPCA Involved

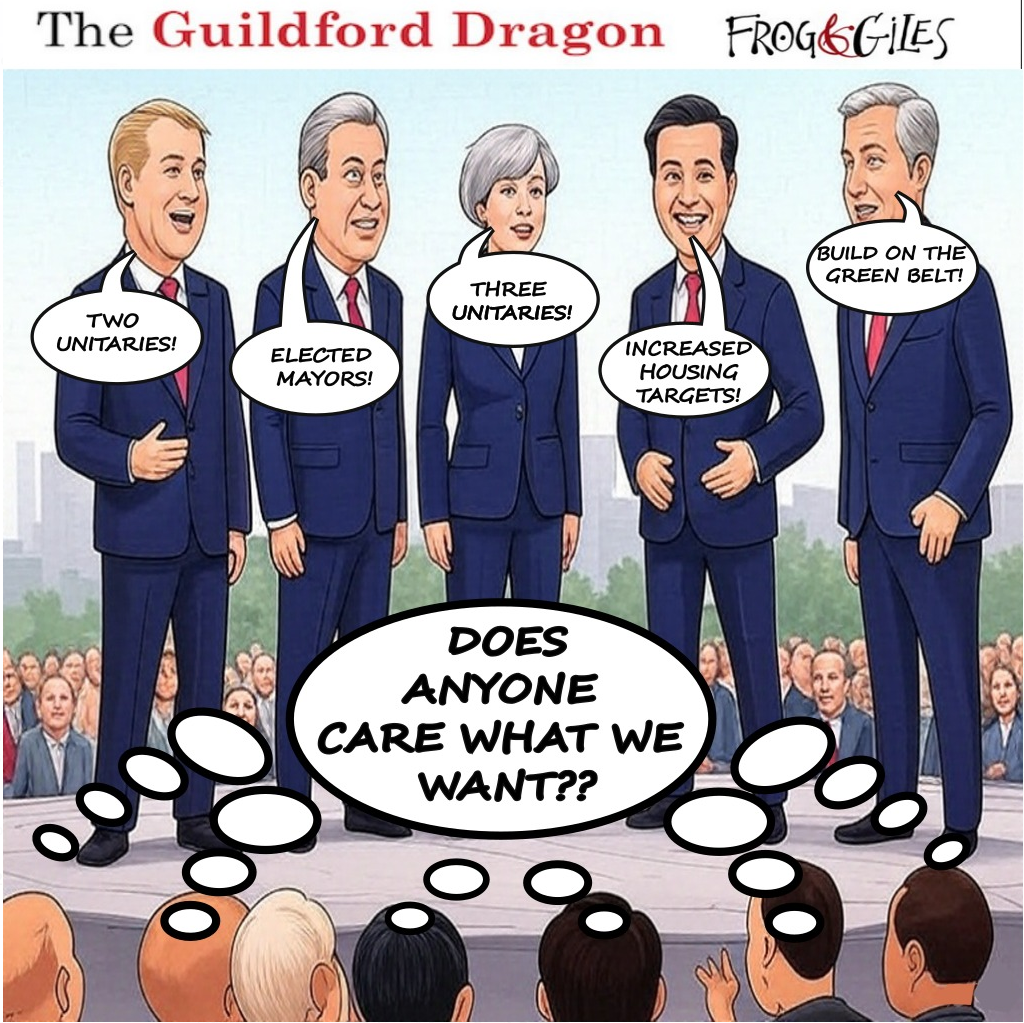

- Comment: We Need Change But Not the Kind Being Imposed By Labour’s ‘Devolution’

- Birdwatcher’s Diary No.326

- Trans Protest on Guildford High Street

- Notice: Open Mic Night at the Institute

- Teenage Suspects Arrested After Report of Indecent Assault

- Highways Bulletin May 5 – Open Day at Merrow

- Letter: Government Statements on Council Reorganisation Leave Me More Nervous Than Ever

Recent Comments

- Jack Bayliss on Suspected Fox Poisonings Shock Guildford Resident: Police and RSPCA Involved

- Roy Darkin on Concerns Grow over Tree Felling on Loseley Estate During Bird-nesting Season

- RWL Davies on Open Letter: Why Am I a Lower Priority for Housing?

- Howard Moss on Guildford High Street, Then and Now – Nothing Can Stop Evolution

- Warren Gill on Guildford High Street, Then and Now – Nothing Can Stop Evolution

- Aubrey Leahy on Guildford High Street, Then and Now – Nothing Can Stop Evolution

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

John Lomas

September 6, 2017 at 12:51 pm

For comparison; what are the carbon and capital costs of producing and distributing hydrogen?

Nobby Bell

September 6, 2017 at 5:30 pm

Solar power is on an exponential rise but Leaf is not the only electric vehicle (EV). A hydrogen network would need to be created, electricity network exists.

Mervyn Granshaw’s argument was outdated when he started the letter and ancient history by the time he had finished. Such is the pace of advance in renewable energy.

John Perkins

September 6, 2017 at 8:10 pm

A hydrogen network does exist. The outlets are known as petrol stations.

Martin Elliott

September 7, 2017 at 10:10 pm

Have you tried getting planning permission for hydrogen storage and dispensing? Even with backing of a IG company, petrol (energy) company, transport operator (buses) it’s very difficult. None I was involved with as a consultant got approved.

Self generation wind/solar for electrolosis, compression and storage isn’t practical so you either go on grid or transport by road. It takes a full sized HGV to draw a trailer that carries only 300kg of hydrogen.

I’ve not even started on the economic case; with or without the massive taxation shifts?

John Perkins

September 8, 2017 at 8:59 am

I’m sure these problems are difficult to resolve, but they are not insurmountable. If the subsidies given to other renewables were available for hydrogen production and distribution then a way would be found.

Planners seem to have no problem casting aside consideration for the green belt, so it should also be possible to persuade them to accept changes which do not have any such deleterious effect.

Tax on hydrogen bought at a pump falls to the consumer whereas tax on electricity taken from the grid falls on everyone.

Martin Elliott

September 6, 2017 at 6:31 pm

Thank you for an eloquent exposure of just some of the Inconvenient Truths of Green/Carbon free electric vehicles. Its not just the Leaf but all battery electric vehicles this applies to.

Unfortunately, despite the rising popularity, hydrogen from my 40 years experience of the Energy Industries, including both gaseous and liquid hydrogen, it also has similar issues. It may be a very common element, but there is virtually no source of it as an element. To get hydrogen as a fuel it has to be split from compounds like water. So you have to expend energy to get this store of energy. Guess what, the most common/effective methods are electricity (small/medium) or fossil fuels (large) again with an energy loss of 20-40%!

As a compressed (or liquified) gas the technology of storage, transport and fueling points is very mature. The hazards are somewhat different to liquid FF. Maybe that’s what puts off Local Councils giving planning permission at most petrol stationseven for trials such as buses.

Even then, although the amount of energy per kilogram is good, even compared to petrol/diesel, energy per cubic metre isn’t because its so light.

A modern HGV carrying hydrogen in bulk weighs over 32 tonnes, but only carries 300kg of hydrogen gas!! Whatever happened to the metal hydrate storage?

That’s just discussing the hydrogen fuel. The fledgling industry is moving from ICE to fuel cells. They’ve been used in transport for over 50 years, but we still don’t know the long term potential; all good or some problems like batteries.

Ben Paton

September 6, 2017 at 7:33 pm

Electric cars are not the solution. This is not only because most electricity is generated by burning fossil fuels. It’s also because if all cars were electric there isn’t the copper supply to make all the electric motors.

The solution is hydrogen. Electrolyser technology from ITM Power can electrolyse water into oxygen and hydrogen at a cost for the hydrogen that is lower than the price of the equivalent amount of petrol. Anyone with solar panels would be able to store the electricity they generate as hydrogen – and use it to fuel their cars.

Existing combustion engines can be converted to run on hydrogen and hydrogen refuelling stations can be created on the road network.

All much more sustainable than electric cars.

Christopher Fairs

September 7, 2017 at 1:06 pm

I believe electric vehicles offer a considerable advantage over internal combustion engine propulsion and that battery technology is preferable to the use of hydrogen. The latter has many problems with its production, distribution and storage but could well prove useful in shipping.

Every mode of transport produces CO2 somewhere in a vehicle’s production and associated use but, with battery-electric systems, these are far less, even when recharging is through dirty coal/gas power stations.

Thankfully, such power plants are slowly being replaced by solar, wind and greener alternatives. Electric vehicles are much quieter, emit no CO2 or noxious fumes when in motion and the batteries can be recycled or used for static electricity storage.

Oil has served mankind well, albeit at enormous environmental cost. It is time to move on.

Simon Schultz

September 7, 2017 at 9:52 pm

Ben Paton seems to misunderstand how hydrogen fuel cell cars work. They are in fact full EVs, with the addition of a hydrogen fuel cell. It is therefore not possible to adapt internal combustion engines to work with hydrogen.

This is in fact a very good solution to the battery/storage problem, however the same issue about where the electricity comes from applies as battery based EVs. You can use coal based power to run the hydrolysis, just as you can use them to generate grid electricity to charge batteries.

The key thing either way is to move as much of our power as possible over to renewables. Luckily, coal power stations all over the world are going out of business because they cannot compete with solar and wind on price per kWH.

I think hydrogen cars are great by the way. However, it is likely to be a case of betamax vs VHS. There is only one model on sale, the Toyota Mirai, and Toyota have sold only 16 of them in the UK. And there are nine filling stations open in the UK.

At the same time, battery EVs are on the verge of reaching a tipping point, with 191 fully EV car models due out over the next several years.

Let’s hope they get off the ground though, because it would be good to see these technologies compete. Either way, the internal combustion engine is now a dead end technology.

Ben Paton

September 8, 2017 at 8:38 am

Mr Schultz should read what I wrote. I haven’t misunderstood at all. Fuel cells combine hydrogen with oxygen to create electricity and water. Some experimental buses and cars use fuel cells to generate their electricity – rather than batteries.

If Mr Schultz read what I wrote he will see that I was talking about burning hydrogen in conventional – but adapted – combustion engines. This is similar to adapting a petrol engine car to run on liquified petroleum gas or LPG.

Fuel cells are a very new technology and the chemistry is complex. Combustion engines have been around for over a hundred years and there’s massive infrastructure in the combustion engine supply chain that could turn out engines that burn hydrogen rather than petrol.

Electrolysis using electricity to split water is the reverse of what fuel cells do. ITM’s polymer technology could be deployed in electrolysers in every home in the country to convert green energy from solar panels into ‘free’ hydrogen for use as a fuel.

Fuel cell cars are the worst of both worlds. They require hydrogen fuel – and so have the same gas storage issues. And they require electric motors that use large quantities of precious resources like copper. And on top of all that the car maintenance and repair industry has no capability to support and repair fuel cells, which are fragile, short life devices.

Mervyn Granshaw

September 8, 2017 at 10:42 am

Two others factors I didn’t mention in my letter spring to mind.

Firstly, the amount of lithium resources and reserves available may be okay now but once the EV tipping point is passed (if it ever is) the exponential rise in demand may well outstrip easy supply and near 100% recycling efficiency could be be required apart from any escalating price concerns. Move over Dallas Oil Barons and say hello to Lithium Barons. Perhaps it’s time to invest now?

Secondly, once we move beyond current personal vehicle usage and factor in the expected growth in countries such as India and China, the Elon plan may simply be unsustainable.

John Lomas

September 8, 2017 at 7:18 pm

Another aspect of electric vehicles is the number of different discrete charging systems.

Imagine the difficulties with ICE vehicles if ESSO, Shell, BP, Texaco etc etc all had different sized and shaped nozzles on their fuel pumps.