Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Mystery Now Likely Solved: How Yorky’s Railway Bridge Got Its Name

Published on: 28 Oct, 2023

Updated on: 30 Oct, 2023

By Frank Phillipson

The origins of the name Yorky’s (or Yorkies or Yorke’s) bridge to the north of Guildford station, and the reason it was built, have been pondered for many years.

After much delving into records and archives searching for people and businesses with the name York (or variations) and also for those who were Yorkshire-born but residing in Guildford, it is now believed that answers may have been found.

Yorky’s Bridge, October 2023. Photo by David Rose.

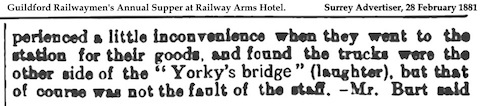

The earliest evidence of the bridge being called “Yorky’s bridge” is in an article in the Surrey Advertiser of February 28, 1881 recording the events at the annual supper of members of the traffic department at Guildford railway station held at the Railway Arms Hotel.

The Railway Hotel (previously Railway Arms Hotel). It stood opposite Guildford railway station in Park Street, demolished in 1963. Picture: David Rose collection.

In a speech by a Mr Miles, referring to businesses calling for their goods he stated: “They often experienced a little inconvenience when they went to the station for their goods, and found the trucks were the other side of the ‘Yorky’s bridge’ but that of course was not the fault of the staff”.

Extract from the Surrey Advertiser, February 28 ,1881, a report on Guildford railwaymen’s annual supper at the Railway Arms Hotel.

The origins of the name must therefore have occurred between 1844 when the railway was being constructed and 1881.

The road that crosses Yorky’s bridge, before the railway came, served as the main access to the large farmhouse of Guildford Park Farm (also known as Guildfordpark Farm and previously as Lodge Farm) from what is now Walnut Tree Close.

The farm was situated on Stag Hill on the eastern side of what had been the medieval royal hunting park of Guildford Park.

The land of Guildford Park was sold to Thomas Onslow in 1709 and became given over to agricultural use with three farms leased to tenant farmers.

As well as being served by a long-established elm-lined access road, the farm may also have had some historical hunting park connection to the River Wey.

As the accessway passed near the river it meant the farm was in a position to receive visitors arriving by boat. As a well-established route, the Earl of Onslow would have almost certainly insisted on the provision of a bridge to maintain access to Guildford Park Farm.

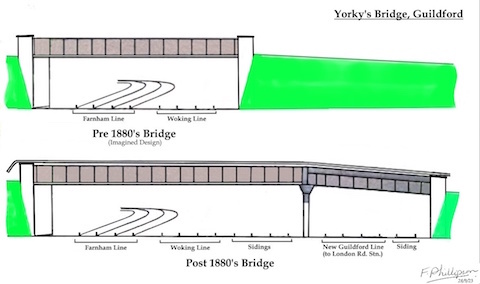

The first bridge in use from 1845 only needed to cross over the two railway tracks that formed the line to and from Woking. It is possible that the bridge may have actually been built to cross over four tracks as the London & South Western Railway [LSWR] was thinking of constructing the line to Farnham which opened in 1849.

Map of Guildfordpark Farm 1816. 1st Series. OS, Crown Copyright Expired.

Guildford Park Farm comprised a large farmhouse and garden, with its farm buildings situated around a large yard close by to the south together with smaller buildings and two ponds.

In 1838 a proposal for a railway from the London & Southampton Railway (later the LSWR) at Woking to a station at Guildford near Farnham Road was made with a Parliamentary Bill submitted to the House of Commons.

This was not successful and led to a further Bill being submitted in 1840 which also did not succeed. Finally, in 1843 a Bill was submitted for the Guildford Junction Railway (GJR) and was authorised by an Act of Parliament on May 10, 1844 to construct the six-mile branch line. The GJR opened on May 5, 1845 but was sold to the LSWR for £75,000.

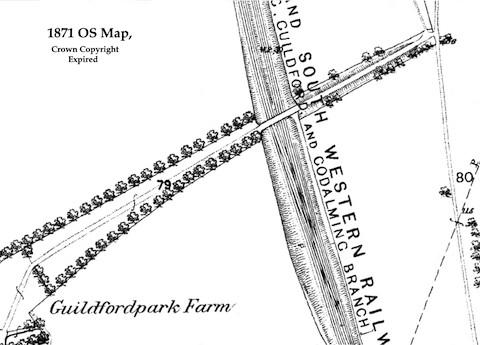

OS Map showing access road to Guildfordpark Farm 1871.

The owner of Guildford Park Farm, including the access to it, was the Earl of Onslow who leased it to Samuel Harwood of Belstead near Ipswich on March 1, 1825.

He is noted as the occupier of Park Farm and Bannisters Farm (total of 550 acres) in the 1830 Land Tax Assessment and in the 1832 Guildford electoral register although his abode is given as Belstead Hall, Ipswich.

Ownership of land entitled the owner a vote in any local election. He is also named as the occupier of the land in February 1838 in the initial railway proposal. He died in October 1838 but it is possible that the lease was continued with his son Samuel Harwood junior as the Guildford electoral register for 1844 lists him also of Belstead Hall, Ipswich.

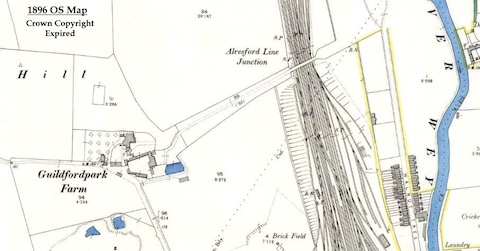

OS Map of Guildfordpark Farm 1896.

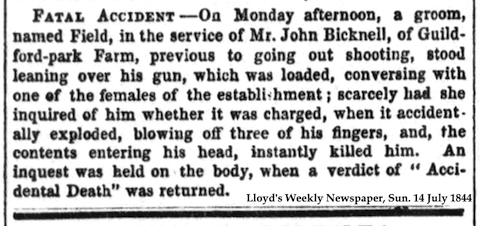

However, it seems that John Bicknell was resident at Guildford Park Farm in 1844 as a report of an accident where a groom called ‘Field’ was killed by a gun going off, which was published on July 14, 1844, names him as resident at the farm (Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper).

Accident Guildford Park Farm July 1844.

There is also some record of Bicknell being resident at Wilderness Farm in the 1844-45 electoral register and the 1851 census. In the 1851 census, Guildford Park Farm was occupied by John Baker and his family, a farmer of 500 acres with 28 labourers.

Sometime in the latter part of 1844 it seems that a Charles Richard Harrison took over the lease of, and also resided at, Guildford Park Farm. Born in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1806, he was the son of a wealthy land and timber merchant Richard Harrison. In the 1841 Census Charles is described as a farmer living at Octon Lodge, Thwing, Yorkshire.

It is this Yorkshireman who it is most likely to be the person who the bridge was named after.

Upon his father’s death Charles Harrison came into considerable property. Brought up as a timber merchant he declined to follow that profession and became extravagant and took up farming taking on two farms at Guildford. He was also involved in field sports and had a sporting stud at Hockton in the East Riding near Hull.

On August 11, 1844 Charles Harrison had just mown a field of clover at Guildford Park Farm when he saw William Legg enter the field and gather up a small bundle of clover, tie it off, and take it away. Harrison immediately went up to him and asked him to come to the farm house. Legg said that he was exceedingly sorry for what he had done and wouldn’t do it again.

However, the following Saturday, Harrison had Legg taken before the magistrate Lord Lovelace who straight away had him committed for trial and taken to jail. Legg was described as a respectable-looking poor man of excellent character who only wanted the clover for his rabbit. The value of the clover taken was one penny.

On Monday September 9, 1844 the Surrey Sessions were held at the Court House, St. Mary’s, Newington, before Mr T. Puckle, chairman. For the case against Legg a Mr Locke appeared for the prosecution, and a Mr Charnock defended the prisoner.

Mr Charnock commenced the defence as follows:

Mr Charnock: “And pray what might be the value of the clover?

Harrison: “One penny.”

Mr Charnock: “Yes, and a very pretty case to send to the sessions. But I believe you did not wish to have the prisoner committed?”

Harrison: “Oh, if you want to know, you may ‘axe’, as they say in Yorkshire.” (Roars of laughter).

Mr Charnock: “May I? Well, I must say, you are very communicative.”

Harrison: “Oh, nonsense; I want no balderdash. I saw the prisoner go into the field and take the clover. Come, now, get over that if you can.”

Mr Charnock: “Well, facts are stubborn things; but still you did not wish to have the prisoner committed if you had not been prompted by the Noble Lord.“

Harrison: “I tell you he took the clover, and, as to the rest, you may ‘axe’.” (Laughter).

Mr Charnock then complained that such a petty case had been sent to the sessions. He said a penny prosecution, which required such a vast expense on the county, didn’t reflect well on the administration of the law in the country.

Mr Puckle, the chairman, replied: “No, Mr Charnock, it is not the administration of the law, but the law itself. If the committing magistrate (the Earl of Lovelace) was of opinion a felony had been committed, he was bound to send the prisoner for trial admitting even if the property was only of the value of a farthing.”

The jury found the prisoner guilty, and he was sentenced to seven days’ solitary confinement in Brixton Prison after having already spent nearly a month in jail.

In the autumn of 1845, Charles Richard Harrison’s behaviour became exceedingly wild and he was placed in Moorcroft House Asylum, near Uxbridge.

There he threatened the life of Mr Taylor, surgeon, and having been prevented from harming him, he became morose and sullen, and it was necessary to feed him with a stomach pump.

In May, 1846, he managed to escape from Moorcroft House, and visited Guildford, where Mr Taylor, the surgeon, lived. He was intercepted and again placed in the protection of friends, who had him confined at Osborne Wick House, in Yorkshire.

While there he had a cunning plan for his escape. He forged a letter and signed it with the name of Mr Ellice, the proprietor of Osbourne Wick House, sanctioning his discharge. He thus made his escape, but by the aid of the electric telegraph he was detained at Derby. He was taken back to Osbourne Wick House, where he threatened the lives of the medical staff.

On February 5, 1847, he again made an escape and was captured at Leeds, armed with two loaded pistols. Fortunately, he was prevented from doing any harm and was sent to a Dr Philp’s Kensington House Asylum, where he became more composed.

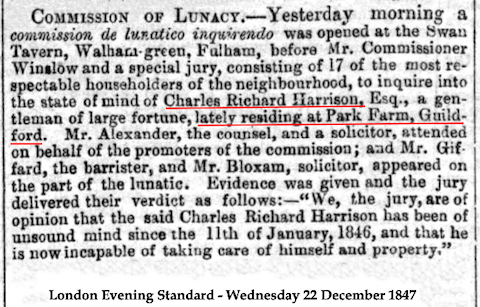

On December 21, 1847 a commission of lunacy was opened at the Swan Hotel, Walham Green, Fulham, to inquire into the state of mind of Charles Richard Harrison aged 42, an inmate of Kensington House Asylum.

Newspaper report of Commission of Lunacy of Charles Richard Harrison December 1847.

Dr Philp, stated Harrison was a suicidal patient, and that he frequently spoke of the Emperor of Russia, and talked of seeing angels and visions, and was decidedly of unsound mind. He imagined himself a king, and spoke of fighting a duel.

After Sir Alexander Morrison gave similar evidence, the unfortunate man was brought into the room. He was described as “a fine man, and of military air, and wears a full moustache”.

In answer to the commissioner’s questions, Harrison said that he had seen his wife descend from the sun in a balloon; that it was his intention to go to Russia, as he detested England; and he believed his brother-in-law, Mr Graybourne, would die in chains.

He repeatedly burst into tears when referring to his wife, who he called an angel. After a lengthy inquiry, during which he showed great shrewdness in some of his replies, Harrison left the room.

The jury found that Harrison had been insane since January 11, 1846 and that his property was stated to be valued at about £12,000. He returned to be confined at Kensington House Asylum.

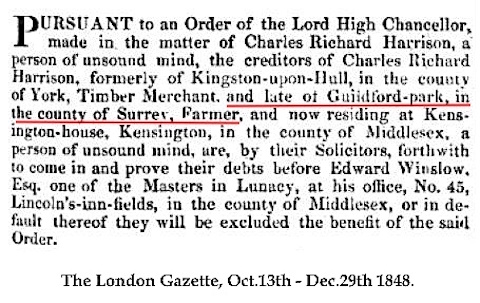

Notices were posted in newspapers asking creditors of Harrison to contact Edward Winslow a “Master in Lunacy” at his office in Lincolns Inn Field, London.

Notice to creditors of Charles Richard Harrison, October-December 1848.

Charles Richard Harrison died aged 49 on May 22, 1854 at Upton, Torquay and is buried at St Mary Magdalene church, Upton.

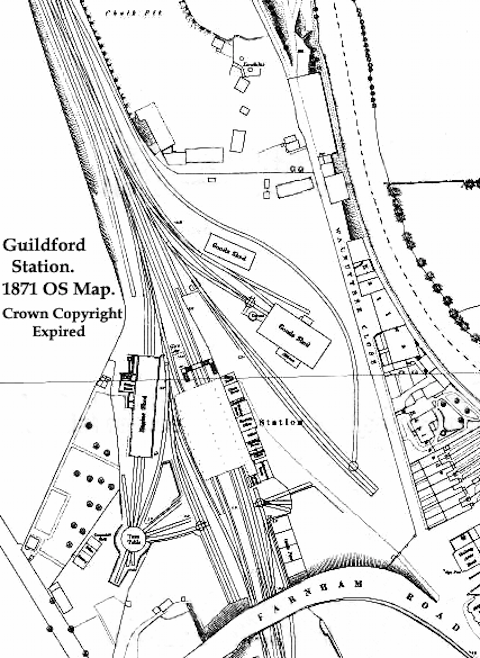

Old Guildford station layout 1871 OS Map. Crown Copyright Expired.

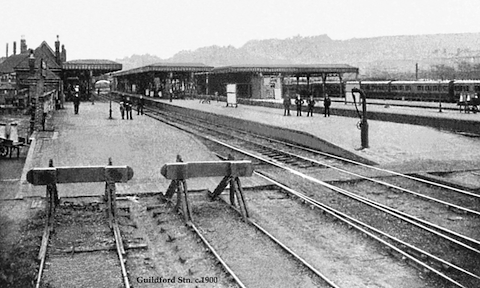

Guildford railway station c.1865. Viewed in low sunlight. Railway Magazine, May-June 1947.

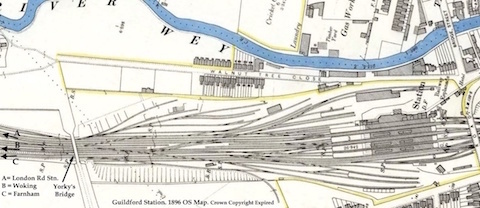

In the early 1880s the whole of Guildford railway station was rebuilt and enlarged after many complaints of its inadequacy (including from the Earl of Onslow).

It also provided additional room for the New Guildford line (opened on February 2, 1885) from Effingham, to enter the station. Part of this entailed replacing the existing Yorky’s bridge with a longer version to cross over the new line.

Guildford railway station layout 1896 OS Map. Crown Copyright Expired.

Picture postcard view of Guildford railway station c.1900s.

Drawing of two versions of Yorky’s Bridge, pre- and post-1880s.

Once an access to a hunting park and farm, Yorky’s bridge is now a main pedestrian route for students from the University of Surrey to Walnut Tree Close and access to central Guildford.

View looking up the footpath to Yorky’s Bridge from Walnut Tree Close, October 2023. Photo by David Rose.

Yorky’s Bridge looking west towards the University of Surrey, October 2023. Photo by David Rose.

View of Yorky’s Bridge looking east towards Walnut Tree Close, October 2023. Photo by David Rose.

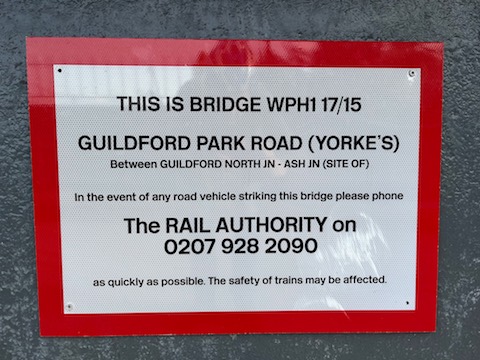

Network Rail’s plaque on Yorky’s Bridge. Note: the latest spelling “Yorke’s Bridge”. Photo by David Rose.

It is also a well-known location for railway enthusiasts to observe train activity and from where numerous railway photos are taken, a selection of which over several decades are seen below.

Looking towards Guildford railway station, October 2023. Photo by David Rose.

These photos have been kindly supplied by Geoff Burch. The photographers and owners of the photos are listed in the captions. Copying these and all images in this story for use elsewhere is not allowed. Thank you.

View towards Guildford railway station. c.1970. Photo by Les Mills. Geoff Burch collection.

N class locomotive 31408, as used on the Reading to Redhill line. Photo by Dave Salmon. Geoff Burch collection.

BR Standard 4MT locomotive 76066 at North Box Sidings. Photo by Gerald T Robinson.

M7 tank locomotive 30055. Photo by Dave Salmon. Geoff Burch collection.

2MT tank locomotive 41301, as used on the Guildford to Horsham branch. Photo by Dave Salmon. Geoff Burch collection.

N class locomotive 31411, North Box Sidings. Photo by Dave Salmon. Geoff Burch collection.

4-COR-4-BUF units 3123 and 3081 leaving Guildford forming a Portsmouth-Waterloo service with unit 3114 stabled in a siding. July 18, 1970. Photo by Gordon Edgar.

LMS Coronation Class, No.6229, Duchess of Hamilton, on a steam excursion train. Photo by Dave Salmon. Geoff Burch collection.

Class 47 diesel, on an inter-regional train, pictured in 1983. Photo by Gordon Edgar.

Responses to Mystery Now Likely Solved: How Yorky’s Railway Bridge Got Its Name

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

H Trevor Jones

October 28, 2023 at 9:41 pm

In Network Rail’s plaque on Yorky’s Bridge, I think “WPH1” means section 1 of the line from Woking to Portsmouth Harbour.

Every section of national rail track has, I recollect, a four-character code of three letters and one digit.

That’s what I remember from working briefly for Network Rail as a data-entry clerk for a short spell in the 2000s after giving up a career in IT (when I no longer kept up-to-date with IT) and before my last paid employment working briefly as a revenue protection data analyst for South West Trains (now South Western Railway).