Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

New Evidence Comes To Light On Wartime Aircraft Crash

Published on: 3 Apr, 2017

Updated on: 14 Apr, 2017

Frank Phillipson tells the story of an aircraft from Vickers at Brooklands that crashed at Haines Bridge, Weybridge in 1945. It claimed the life of an experienced and decorated test pilot, Squadron Leader Maurice Victor Longbottom DFC. This article also tells his fascinating story.

As a boy Tim Ely, now of East Horsley, was one of the only people to witness the last moments of an aircraft from Vickers at Brooklands before it crashed on the railway line in Weybridge.

It took place at 3.25pm on Saturday, January 6, 1945, and claimed the life of an experienced and decorated test pilot, 29-year-old Squadron Leader Maurice Victor Longbottom DFC.

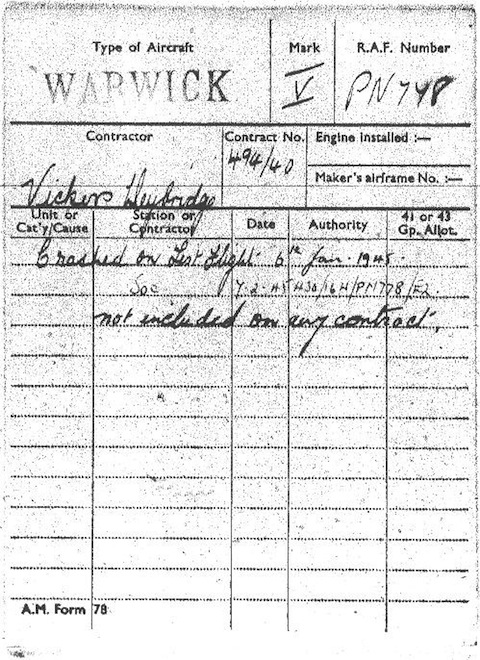

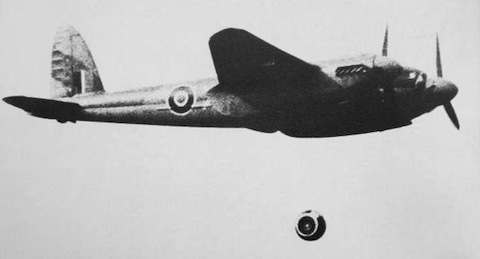

Nicknamed ‘Shorty’ Longbottom, he was test flying a Vickers Warwick twin engine aircraft from Brooklands airfield, where the Vickers-Armstrong aircraft factory was located. The Warwick was similar in appearance to the better known Vickers Wellington bomber but was slightly larger. The actual aircraft that crashed was a Warwick GR Mk.V, Serial No. PN778.

Vickers Warwick GR.V No.PN743 of 179 Sqdn. Courtesy of J Visschedijk, 1000aircraftphotos.com Click to enlarge in a new window.

The Warwick was built to a prewar specification for a two-engined heavy bomber. However, the high- power engines it needed were not available and by 1941-42 the four-engined heavy bombers such as the Handley Page Halifax and the Avro Lancaster were carrying out this role. The Warwick was therefore re-designated either as a General (actually Maritime and Anti-Submarine) Reconnaissance, Air Sea Rescue (dropping life rafts or life boats) or as a Transport aircraft.

Tim, aged 11 at the time, recalls: “During the Second World War, my father’s work at the Ministry of War Pensions in London was evacuated to Blackpool. My brother Tom, who was nine years older than me, had gone over to France on D-Day. In January 1945 I was living with my mother and my elder sister in Weybridge.

“I pedalled my Hercules bicycle to Sir Richard’s Bridge on Ashley Road in Walton-on-Thames. There, I sat on my bicycle, leaning against the bridge parapet and watched the occasional train go by on the Waterloo to Southampton line.”

View of Walton Station from Sir Richard’s Bridge. Author’s picture. Click to enlarge in a new window.

“After a few minutes I was delighted to see a large twin-engined aeroplane, which had just flown over Walton station from the direction of London. It was very low and passed overhead. It continued to follow the tracks steadily, but was losing height, and just short of Haines Bridge it belly landed centrally on the railway, its fuselage in line with the tracks towards Weybridge station.”

View from Sir Richard’s Bridge towards Haines Bridge. The train in the distance is just about to go under Haines Bridge, There would have been fewer trees and other vegetation in 1945. Author’s picture. Click to enlarge in a new window.

Tim says there was an enormous explosion and thinks it may have been caused by the aircraft landing on the four live electric supply rails. He continues: “Clearly no one on board could have survived. I cycled home, told my mother what I had seen and then rode up Oatlands Avenue to see the smouldering wreckage.”

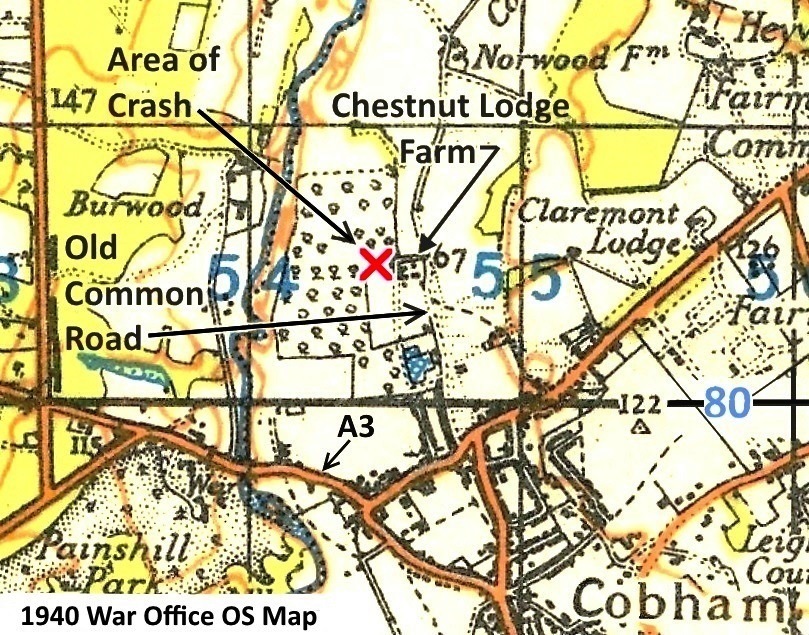

Warwick crash site on the railway line near Haines Bridge. 1940 War Office OS Map Crown Copyright expired. Click to enlarge in a new window.

Another boy, Derek Bridgewater aged 13, also saw the wreckage on the railway. He spotted a large machine gun near the crash site and later that day, with great difficulty, managed to retrieve it. Frightened that his father would find the gun, he buried it as best he could, under a hut behind some greenhouses.

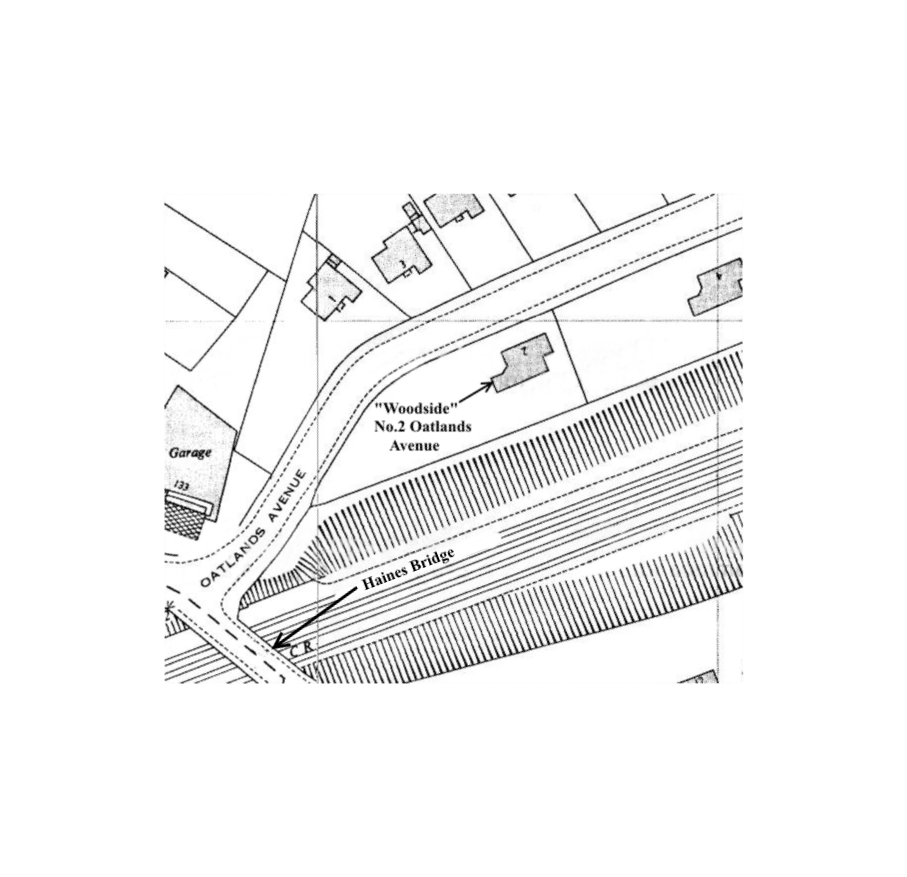

Pamela Morphew (nee Burningham), now of Pirbright, was a schoolgirl at the time and was at home with her mother and two sisters at “Woodside”, 2 Oatlands Avenue, Weybridge. The bungalow backed onto the railway line near Haines Bridge and as the aircraft exploded the kitchen ceiling was brought down. She and her surviving sister confirm that the aircraft landed centrally and in line with the railway facing towards Weybridge station.

‘Woodside’ No.2 Oatlands Ave. Weybridge. 1960 OS Map Crown Copyright expired. Click to enlarge in a new window.

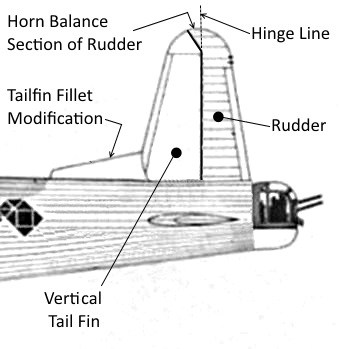

The conclusion as to the cause of the crash was that the aircraft experienced severe rudder over balance (a known problem with the Warwick) and spun into ground. This view is confirmed in a letter to Linda Longbottom from fellow Vickers test pilot Bob Handasyde, dated February 2, 1945. He states that there has been a further accident on February 1, 1945 during a test flight “to investigate the rudder trouble suspected in Maurice’s accident”.

British bombers at this time did not have power-operated control surfaces (such as the rudder) but just relied on the strength of the pilot moving them directly via cables or rodding. To ease these considerable loads, the rudders were aerodynamically balanced; that is, part of the rudder control surface was projected in front of the hinge line (horn balanced), see diagram.

The air load on this forward rudder projection acted to oppose (or balance) the loads on the rest of the rudder control surface, considerably easing the manual force required.

The design of the Warwick vertical tail fin, under certain conditions and configurations such as when carrying out a sideslip, caused it to stall. This resulted in turbulent air flow over the stalled fin that then caused the rudder to overbalance (the full force of the air flow acting on the horn balance section ahead of the hinge).

This, suddenly and without warning, then caused the rudder to lock over to full right or left rudder and be almost impossible to correct due to the enormous forces involved. The problem was eventually solved by the addition of a forward tail-fin fillet and reduction of rudder trim tab travel.

The conclusion as to the cause of the crash is believed to have been based on eye-witness accounts of the aircraft entering two spins. These were deliberately carried out to try to induce the rudder over-balance problem and then find a way of recovering the aircraft.

‘Shorty’ Longbottom successfully managed to recover the aircraft from the first spin and then entered another spin. However, the witnesses at the coroner’s inquest did not see that ‘Shorty’ was also able to recover from the second spin. Viewing from some distance away they were mistaken in thinking he had immediately crashed vertically onto the railway line having failed to recover from the second spin.

Report of the coroner’s Inquest from the Surrey Advertiser, January 20, 1945. Click to enlarge in a new window.

However, this was not the case. Tim saw that the aircraft flew in level flight along the railway and belly land on the track. ‘Shorty’ must have made a supreme effort and managed to pull out at very, very low level and tried to make his way back to Brooklands following the railway.

However, because of the extreme stresses the aircraft had come under in the spins and pulling out, it is possible that airframe structure must have failed in some way and ‘Shorty’ was unable to maintain height.

Alternatively, it’s possible that he struck his head on some part of the aircraft during the manoeuvres and became concussed. Still able to pull out of the spinning dive, the effects of the injury then became more severe which led to the crash at Haines Bridge.

Due to the final spin being carried out some distance away from these witnesses, there seems to have been no connection made between where the crash would have occurred if ‘Shorty’ had failed to recover from the spin and the actual crash location.

Police Sergeant Benjafield reported that the aircraft came down on the railway line 50 yards east of Haines Bridge. An entry in the Surrey Police Day Book recorded that the aircraft burnt out on the railway line and a guard was placed on the wreckage by Vickers personnel. It also noted that there was “some obstruction of the railway line”, but steps for its clearance were taken immediately after RAF Faygate (an RAF maintenance unit near Horsham responsible for recovery of crashed aircraft) was informed.

View from Haines Bridge towards Sir Richard’s Bridge with the crash site 50 yards away. Author’s picture. Click to enlarge in a new window.

The coroner’s inquest into the crash recorded a verdict of accidental death. Witness, Arthur Watmore, thought the pilot had purposely landed on the railway line to avoid hitting houses, although this seems unlikely and there is no corroboration of this from any other witness.

At the coroner’s inquest, Vickers employee Alan Waller said that he had inspected the aircraft and that it was thoroughly airworthy. Fellow employee James Hatcher said that he had started the engines of the aircraft and that Longbottom had then taken off perfectly normally.

Harry Zeffert, an electrical supervisor in the Vickers Experimental Department, thought that Longbottom was the most intrepid pilot he ever saw and that he was capable of getting an aircraft to do anything he wanted (from a recorded interview held by the Imperial War Museum). On that morning ‘Shorty’ told Zeffert that he was going to take one of the “Warwicks” up as he thought that the crashes were only due to the inabilities of the other pilots. He said that he thought that he knew how he could recover the Warwick from any spin that it got into.

The day before the crash Vickers chief test pilot Joseph ‘Mutt’ Summers and his flight observer, Jimmy Green, were test flying Warwick GR Mk.II, HG364, when at about 3pm its controls became locked at full rudder.

The aircraft was at 3,000 feet over St George’s Hill in Weybridge. At that height there was no time to quickly bale out and in the resulting crash an avenue of young trees cushioned the plane’s impact with the ground. The aircraft ended up in a ploughed field near Chestnut Lodge (Farm), Old Common Road, Cobham.

Warwick crash site near Chestnut Lodge, Cobham, January 5, 1945. 1940 War Office OS Map Crown Copyright expired. Click to enlarge in a new window.

As the aircraft come to rest, flames emerged from both engine air intakes. Before the fire really took hold and eventually burnt the aircraft out, some farm workers had enough time to get into the fuselage and rescue Summers and Green. Both men were injured and were taken to Weybridge Hospital. A guard of one corporal and three men from RAF Hook (a barrage balloon depot) was placed around the wreck.

A further Warwick crash caused by the rudder over balance problem occurred on February 1, 1945. This flight was in an aircraft (one of four) specifically allocated to investigate the problem and ways of overcoming it. Warwick GR Mk.V, Serial No. PN777 took off from Brooklands about midday with Vickers test pilot, Wing Commander Maurice Summers (brother of Joseph ‘Mutt’ Summers) at the controls and accompanied by flight test observer, George Hemsley.

At 13,000ft Summers deliberately put the aircraft into a spin but immediately rudder overbalance locked the rudder over to starboard. Finding it impossible to regain control he told Hemsley to bale out and soon followed himself.

The aircraft continued to fall in a wide spiral and eventually landed on numbers 14 and 16 Ruxley Lane, West Ewell at 12.25pm. It completely demolished number 14 and killed Annie Swan and her visitor Edith Connor.

Hemsley landed in a field alongside Reigate Road, Epsom and suffered an ankle injury. Summers landed in Highfield Drive, Ewell and suffered a head injury when his parachute dragged him across a road.

Maurice Victor Longbottom was born in West Derby, Liverpool on February 13, 1915. He was educated at Merchant Taylor’s School in Crosby, the Wigan Mining and Technical College and at Liverpool University. In 1934 he became an operator first class in the Royal Navy Wireless Auxiliary Reserve.

In 1935 Longbottom learned to fly at Bristol Flying School, Filton and became a sergeant pilot in the RAF Reserve. He was commissioned in 1936, being made a Flying Officer in 1938, and Acting Flight Lieutenant in 1939. Being of no great stature he soon acquired the nickname of ‘Shorty’.

Saunders Roe London flying boat. CH1922 IWM Non Commercial Licence. Click to enlarge in a new window.

In the late 1930s Longbottom served with 202 Squadron equipped with Saunders Roe ‘London’ flying boats and based mainly in Malta but also in Egypt and Gibraltar.

The main concern for Britain in the late 1930s was the rise in Italian military preparations in the Mediterranean and Red Sea. Longbottom, 202 Squadron and other RAF squadrons therefore flew photo reconnaissance missions and took photos from international waters of the Italian island of Pantellaria (midway between Sicily and Tunisia) where a vast underground aircraft hanger had been built, new military installations on the Italian Dodecanese Islands along the Turkish coast, submarines along the coast of North Africa, new airfields in Libya, areas of Italy which might be used to invade French Corsica, and fortification of Italian possessions along the west coast of the Red Sea.

In 1939 (prior to September) Australian Sidney Cotton together with Canadian RAF Flying Officer Robert “Bob” Niven (flying as a civilian) were clandestinely taking aerial photographs of German and its allies’ military installations for MI6 and the French Deuxieme Bureau. They used a Lockheed 12A Electra Jr executive aircraft with secret camera compartments which enabled them to fly as a civilian aircraft directly over German and Italian territory at high altitude.

They discovered a way to prevent the camera mechanism from freezing up and stopping the lens from fogging at higher altitudes. They achieved this by diverting the executive aircraft’s cabin heating to flow over the cameras.

In 1939 on a photographic mission they were flying from Malta, Cotton and Niven met ‘Shorty’ Longbottom. On June 15, 1939 the three men flew in Cotton’s aircraft to covertly photograph a number of towns on Sicily.

On return to Malta the photographs were processed and turned out to be excellent. ‘Shorty’ was not allowed to go along on further flights with Cotton and Niven, probably because he was a serving RAF officer on Malta. However, he, Cotton and Niven were able to talk about how aerial photo- reconnaissance should develop.

Cotton found that ‘Shorty’ was passionate about aerial photography and described him as “a young man with a slide rule mind”. He also said that Longbottom was an expert on the RAF’s F24 camera and taught them some little known techniques in its use.

In August 1939 ‘Shorty’ submitted a paper called ‘Photographic Reconnaissance of Enemy Territory in War’ to the Air Ministry. It was a collaborative effort by Cotton, Niven and Longbottom but written and submitted by ‘Shorty’ Longbottom as he was a serving RAF officer at the time.

It suggested that photographic reconnaissance would be better carried out by small fast aircraft stripped of unnecessary weight and fitted with additional internal fuel tanks and cameras a fact which Cotton and Niven had previously discussed.

It would be unarmed relying on speed, high rate of climb and flying at high altitude to avoid enemy defences. The idea was put aside as there were not enough Spitfires (the aircraft they envisaged using) to be spared for the project.

When Cotton was recruited as an Acting Wing Commander in September 1939 to form a photographic reconnaissance unit for the RAF (the Heston Flight), he arranged to have Longbottom transferred to the unit as well as Bob Niven. The Heston Flight was renamed No.2 Camouflage Unit (a cover name) from late September 1939. They were designated ‘White Flight’ while in the air to identify them to Fighter Command.

The use of twin-engine Bristol Blenheims and single-engine Westland Lysanders for photo reconnaissance work had shown their vulnerability to enemy attack. Cotton therefore pushed ahead with the idea of small fast unarmed aircraft for the job and managed to persuade Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding commander of Fighter Command to release two Spitfires to be converted for photo reconnaissance.

The two aircraft were based at Heston where they became known as the “Heston Special Flight”. Their eight Browning .303 machine guns and radio were removed and replaced by cameras and additional fuel tanks.

Converted Mk 1 Spitfire N3071 (now PR Mk.1a) was flown by ‘Shorty’ from Heston to Seclin in northern France on November 5, 1939 to commence photographic flights over areas of Germany near the French border. Bob Niven flew over a supporting group of eight ground crew in the Flight’s Lockheed 12A Electra Junior. The detachment was known as the ‘Special Survey Flight‘, but later renamed 212 Squadron and was also later based at Lille, Nancy, south-eastern France and for a time on Corsica.

The first ever high-speed, high-level unarmed photo reconnaissance sortie was flown by Longbottom from Seclin on November 18, 1939 over Eupen in Germany. The intended photographic target had been Aachen but a slight navigation error saw him over Eupen. However, the results from his flight were excellent and further sorties were then flown over various German cities and military installations.

At their operational height of 30,000 to 35,000 feet the temperatures were –50°C. With no cockpit heating the pilots only had an oxygen mask and plenty of underwear for survival. On returning the pilot was usually numb and frozen stiff.

The Flight/212 Squadron returned to the unit at Heston (which had now been renamed the Photographic Development Unit (PDU) since January) just before the fall of France in 1940. Longbottom and Niven were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in March 1940, for their pioneering photo reconnaissance work. They were also offered the French Officer of the Legion of Honour and the Croix de Guerre with palm leaf, but these were stalled by the RAF and eventually turned down.

Longbottom continued to fly with the PDU (which became the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) in July 1940) until the summer of 1940. He then became a test pilot at the RAF Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Boscombe Down.

On July 5, 1940 Maurice ‘Shorty’ Longbottom married Lilian (Linda) Scott Butler in Crosby, Liverpool. They had one daughter, born on November 5, 1943, whom they named Andrea Margaret – Andrea, after Bob Niven’s wife.

In 1942 ‘Shorty’ was seconded to Vickers-Armstrong as a test pilot. It was here that in 1943 he carried out much of the development test flying involving Avro Lancaster bombers in the test dropping of Barnes Wallis’s bouncing cylindrical Upkeep bomb. This was used by 617 Squadron (The Dambusters) on the night of May 16 and 17, 1943 to breach the Möhne and Eder dams in western Germany.

On May 13, 1943 ‘Shorty’ carried out the first and only live fully armed practice drop of the bouncing bomb in the English Channel five miles off of Broadstairs, Kent.

It was dropped from Mk.III Type 464 (Provisioning) Lancaster ED817 (one of three prototype Lancasters modified to carry the Upkeep bomb which did not take part in the Dams Raid) just three days before the raid.

An Upkeep bomb drops from a Lancaster during tests. FLM 2365 IWM. Non Commercial Licence. Click to enlarge in a new window.

The bomb bounced seven times over 800 yards without any deviation, and detonated at depth of about 33 feet and caused a water spout of around 500 feet.

After the Dams raid Longbottom was involved in the test dropping of Barnes Wallis’s smaller spherical bouncing bomb called Highball from the De Havilland Mosquito. The bomb was designed to be used to attack enemy warships but was never used in anger.

On one occasion, when ‘Shorty’ was landing at Wisley airfield with an inert Highball bomb still in place, it became detached due to the forces of the aircraft flaring out as it landed. The bomb proceeded to bounce down the runway over the airfield boundary and demolish part of a cottage. No one was injured and ‘Shorty’ went straight away and apologised to the occupier.

A few months later, with the damage to the cottage now repaired, ‘Shorty’ was again landing with one of the inert Highball bombs when the same series of events occurred! On visiting the damaged cottage to again apologise, the lady occupier said: “Oh no, not you again!”

In January 1944 ‘Shorty’ was ‘transferred to the Reserve’ from the RAF and it seems likely that he then became directly employed by Vickers-Armstrong as a test pilot.

During his career ‘Shorty’ flew more than 90 different types of aircraft and built up nearly 2,000 hours of flying time.

In a letter to Longbottom’s widow, Barnes Wallis summed up his importance by saying: ‘“We all were devoted to your husband, as I expect you know, but perhaps there was especially close link between him and me, for he was so ready and willing to talk over technical problems and we had many discussions together. He was the only one of our pilots with whom one could really plunge into the future, and I miss my contact with him very, very greatly.”

‘Shorty’s’ wife described him as “….essentially an aviator. His whole life was bound up with secret work he was doing, and he could do anything with a plane”.

His elder and only brother Philip was also killed in a wartime aircraft crash while training to fly in America in July 1942. He and seven other RAF flying cadets and an American instructor were flying four twin-engine Cessna AT-17 Bobcats when they ran into bad weather in which all four aircraft collided and crashed killing all the crews.

According to Woking Crematorium records, ‘Shorty’ Longbottom’s funeral and cremation took place on January 13, 1945.

His ashes were scattered, at his wife’s request, by fellow test pilot Bob Handasyde at a location where both men had very much enjoyed pheasant shooting together. Handasyde wrote: “Dear Maurice is now with the Pheasants, etc. which gave him and myself so much pleasure… this last little ceremony … was very simple but I am afraid very sad”.

Maurice ‘Shorty’ Longbottom is commemorated, along with his father, at St Luke’s graveyard, Crosby.

Responses to New Evidence Comes To Light On Wartime Aircraft Crash

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Claire Lee

April 4, 2017 at 1:34 pm

A fascinating article which I probably shouldn’t be reading at work but my office is over the road from the site of the second crash described.

It is good to see an acknowledgement of the service and sacrifice of the crews involved in developing testing and maintaining these aircraft. Especially given that the only way to identify a the source of a problem was to make it happen and then trust that your experience and skill will enable you to get out of it.

They were very brave people.

Dave Lefurgey, Canada

April 4, 2017 at 5:01 pm

Well done and well written, Frank Phillipson.

My uncle was Bob Niven: he and Shorty were best friends. My own family research shows your article to be well researched too.

Fred Winterbotham, their MI6 boss who authored a book on the Enigma story, wrote that Shorty and Niven were deserving of a place in history for developing high speed/ high altitude photo reconnaissance.

Jim Schofield

April 5, 2017 at 10:13 am

A fantastic piece and clearly very thoroughly researched. Thank you.

Dr John Shelton

January 25, 2020 at 12:53 pm

I came across the name of Shorty Longbotton (thanks Google) when researching for my book: R. J. Mitchell at Supermarine.

I found this a well written, researched and illustrated article.

I hope someone writes a book on Longbottom’s varied and sterling contributions to the war effort.

Robert Pawson

December 18, 2021 at 1:33 am

This article is brilliant. Bob Handasyde was my grandfather.

I found the article tonight whilst reading his (my grandfather’s) log books, in particular dealing with his own crash in a Warwick on 2.1.1945 which features on the Wikipedia page devoted to Vickers Warwicks.

I have a copy of the letter my grandfather wrote to Shorty’s widow, in front of me now – a strange feeling.