Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Opinion: 20 Reasons Not to Build on Green Fields

Published on: 26 Jan, 2023

Updated on: 27 Jan, 2023

By David Roberts

What’s the difference between a field and a piece of derelict urban land? Not much from a developer’s point of view – except that the field is likely to be cheaper and easier to build on.

Many people agree. After all, it is argued, we’ve got to build somewhere – we need more affordable houses – and progress is progress.

Wrong. It’s not hard to demonstrate that there is no link between building and affordability, at least in the South East.

Wrong. It’s not hard to demonstrate that there is no link between building and affordability, at least in the South East.

That is the subject of another discussion. But it’s the idea of “progress” that really needs to be put under the microscope, not least because desperate economic times have made “growth” a sacred mantra for Conservatives and Labour alike.

Little value is attached to what’s not growing, our GDP (gross domestic product). A cynic might include new housing estates in this. Building them makes money for some but they then become a non-productive store of capital into which an unhealthy slice of the nation’s wealth is sunk.

From this point of view, housebuilders are robbing the real economy.

More often, however, green fields are seen as useless empty space waiting to be built on. This undervalues the countryside as an inhabited, working environment that also embodies a wide stock of natural, social and cultural capital. By damaging or destroying this capital, thoughtless development can involve high opportunity costs.

These costs are poorly recognised in our sclerotic planning system, which is still stuck in a 1940s rut of social-democratic improvement. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), for instance, recognises only five reasons to protect the green belt:

“a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas; b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another; c) to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment; d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and e) to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.”

All laudable aims, but nothing much else counts in planning decisions.

This is too narrow for a world hurtling towards climate catastrophe and the planet’s sixth great extinction – especially as the latter is due to include us!

A fuller list of actual and potential assets or services threatened by the spread of new housing would have to include:

- Agriculture, forestry and horticulture

- Food security

- Rural business and crafts

- Mineral extraction

- Urban cooling

- Water catchment and supply

- Flood defence

- Noise limitation

- Air pollution control

- Light pollution minimisation

- Carbon storage and sequestration

- Biodiversity

- Recreation and tourism

- Land for parks, burial grounds and other public uses

- Archaeological heritage

- Film and other arts locations

- Civil emergency evacuation and assembly areas

Volumes could be written about each of these; see, for instance, the brilliant 2021 Dasgupta Review on the economics of biodiversity.

But there are three more assets which are harder to sum up but no less concrete:

18. Natural heritage, historical landmarks, traditional views, sightlines and – yes – beauty. All things that we appreciate in a fuzzy way but which add up to a powerful sense of space and place and which ground us in who we are. Aesthetic value is real and not imaginary.

19. Public health and wellbeing, both physical and psychological. The NPPF grudgingly acknowledges these benefits but surely, post-Covid, they deserve to be quantified and factored more sharply into planning decisions.

20. Promotion of social equality based on the ability to share space, public or private, with others.

No one doubts that growing inequality is a damaging issue in advanced economies, or can fail to be uneasy about the spread of gated neighbourhoods, privately policed shopping malls or quarters like Canary Wharf, where surveillance is intense and access by non-conforming individuals, especially the poor, is discouraged.

So much of what we used to have in common is still being privatised and commoditised. Some perceive a historic “loss of the commons” on a par with 16th-century enclosures, gradually turning us from free citizens into compliant consumers.

So who are the real champions of progress? Go-for-growth developers and their political cheerleaders, or rural folk stigmatised as “Nimbys”?

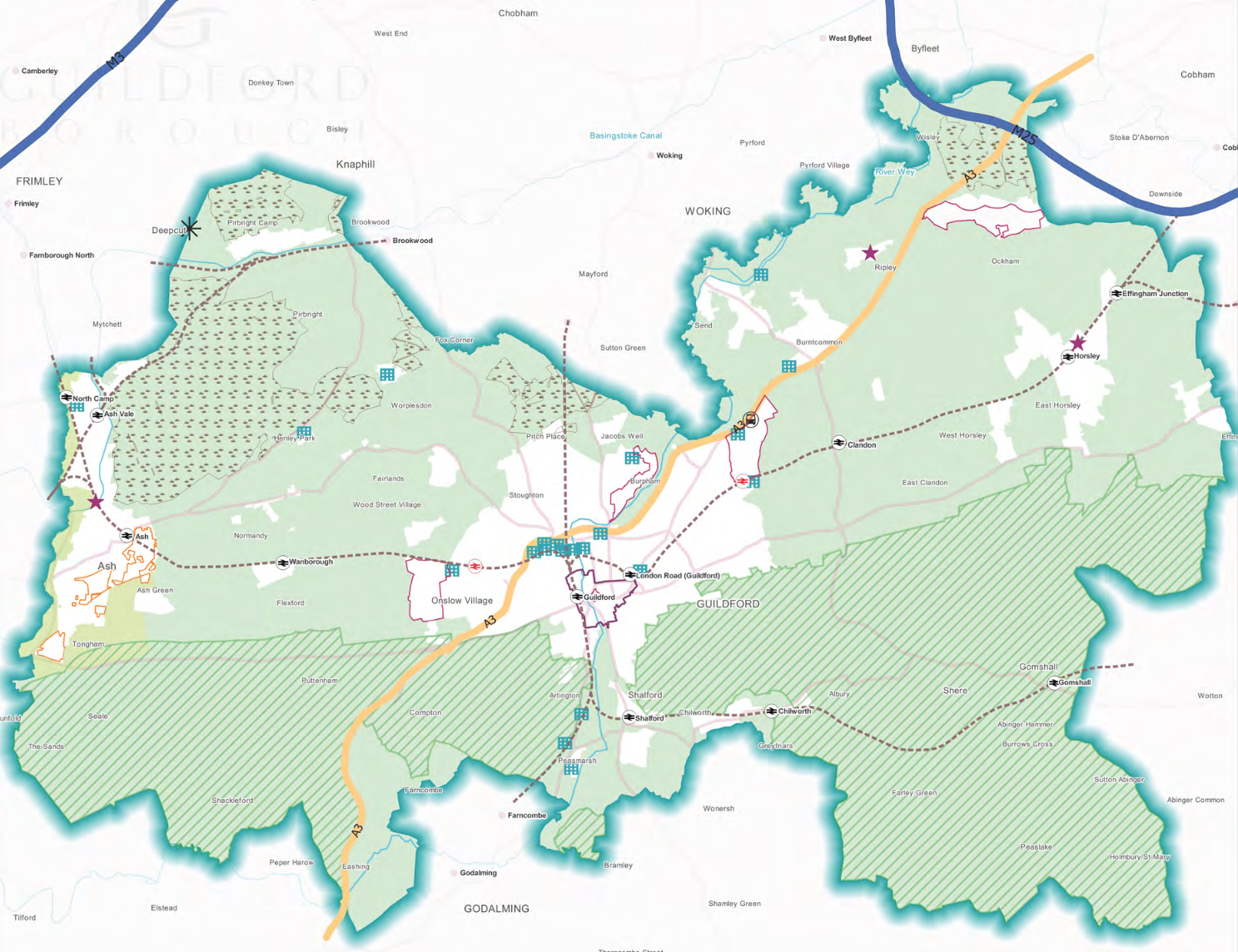

Open fields, like those at the former Wisley airfield, tick many of the twenty boxes above. Yet plans for 2,000 new homes there have provoked far less controversy than for 400 on a derelict urban site in North Street.

Why? Because nature provides most of the twenty ecosystem services listed for free. They therefore count for too little in many people’s minds and are easily squandered, even though they make up much of society’s true wealth.

They deserve to be treated as quantifiable, investible assets whose inclusive value down the generations often outweighs mere bricks and mortar. When will public and planners start to recognise and evaluate them properly?

Responses to Opinion: 20 Reasons Not to Build on Green Fields

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Jules Cranwell

January 27, 2023 at 8:23 am

Well, I can’t argue with any of that. I can’t see that anyone could, apart from the Tory group which handed down their despised Local Plan in their death throes.

On point 19, Public Health and Wellbeing. A recent report illustrated the benefits of green spaces to mental health, particularly of the young. Their mental health problems have increased out of recognition in recent years. Destroying even more green spaces can only exacerbate the issue.

A Walker

January 27, 2023 at 1:55 pm

There won’t be any young people left in Surrey if there are no new houses built for them to live in.

Jules Cranwell

January 28, 2023 at 3:48 am

Mr Walker needs to come and look at the houses being built on what used to be green belt. They are all executive homes. None are affordable as first homes for the young, or for key workers.

David Roberts

January 28, 2023 at 3:44 pm

Why can’t more young people afford to live in Guildford? Because it’s cheaper for developers to build big houses in the countryside.

The Tory Local Plan colludes with them in this. But most young people want to live in town where the jobs and infrastructure are. Hence big new housing estates are appearing in the Horsleys while North Street is refused planning permission.

This is all back to front. There will be no financial incentive to regenerate the town until the countryside is put off limits.