Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

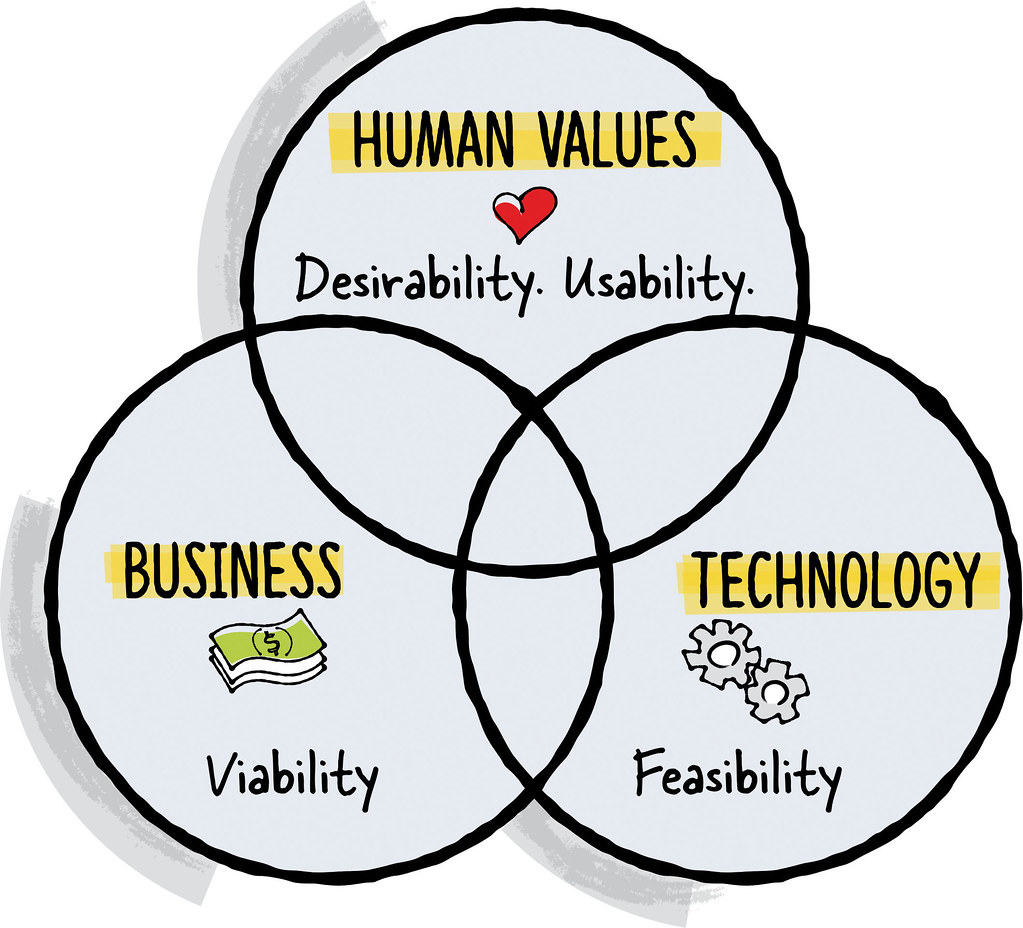

Opinion: Viability Studies – Great for Politicians and Developers, Disastrous for the Community

Published on: 23 Dec, 2021

Updated on: 27 Dec, 2021

Why are developers continually building things they say are not financially viable? Why has the amount of affordable housing provided by developers diminished so dramatically even in the prosperous South East?

Why are developers continually building things they say are not financially viable? Why has the amount of affordable housing provided by developers diminished so dramatically even in the prosperous South East?

Guildford Residents Association member John Harrison outlines the problem of viability studies in planning consents that determine what gets built.

Recent articles in the Dragon about the Debenhams redevelopment, St Mary’s wharf, have talked about the importance of “viability”. Clearly a developer will not build something he does not think is financially viable. But nowadays the term relates to what can be negotiated with the local council, to cover things like affordable housing or in the case of St Mary’s Wharf, a riverside walk and a bridge to the Yvonne Arnaud.

The problem is that the financial viability cannot be definitively determined, only a surprisingly broad range of estimates can be made, as this example based on St Mary’s Wharf illustrates.

The problem is that the financial viability cannot be definitively determined, only a surprisingly broad range of estimates can be made, as this example based on St Mary’s Wharf illustrates.

The calculation is based on the difference between forecast costs and potential total sales prices from all the flats once they are built and sold.

The developer’s application submission shows total revenue of £132.7 million and cost of £125 million giving a difference of £7.7 million and perhaps therefore little room for affordable housing or a footbridge. But if sales revenue was 10 per cent more (£146m) and costs 10 per cent less (£112.5m) the difference would be £33.5m, more than four times as much and an extra £25.8m giving ample scope for funding community benefits.

With several GBC councillors talking about the significance of viability, all the more important that the fluid nature of viability studies is recognised by all concerned.

With several GBC councillors talking about the significance of viability, all the more important that the fluid nature of viability studies is recognised by all concerned.

To facilitate this RICS (Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors whose members prepare these studies) requires the inclusion of a sensitivity analysis showing the range of outcomes similar to my simple example above. I could not find this in the planning application documents on the council website and look forward to reading it as soon as it is uploaded. The range may well be bigger than mine.

In practice, the figures are negotiated between highly motivated developers, whose personal financial incentives are perfectly aligned with the outcome, and who have access to all the information, and the hard-pressed local planning team.

In practice, the figures are negotiated between highly motivated developers, whose personal financial incentives are perfectly aligned with the outcome, and who have access to all the information, and the hard-pressed local planning team.

Guildford Borough Council normally pays consultants to help with the negotiations, and they do their best, but even they can struggle to get accurate figures because developers are reluctant to disclose them.

But crucially, and in reality, it’s only possible to estimate these costs and revenues with limited accuracy, even with the best will in the world, since they have many components and the payments are spread over a significant period, so have to be discounted back to present value, introducing further uncertainty.

Each component has a margin of estimated error which can be exaggerated for the purposes of negotiation. The skill and brinkmanship of the participants in this game of poker is what determines what gets built and what benefits accrue to the community.

Each component has a margin of estimated error which can be exaggerated for the purposes of negotiation. The skill and brinkmanship of the participants in this game of poker is what determines what gets built and what benefits accrue to the community.

As the above example demonstrates, small changes have an exaggerated effect on the bottom line. 10 per cent variation on inputs has 435 per cent impact on the result. Is it any wonder that beautiful architectural solutions tend to get negotiated away early?

This strikes me as an odd way of determining the future of our towns and cities and raising what is effectively a tax. And it’s not just Guildford. In Bishops Avenue, London, colloquially known as millionaires row with some of the capital’s most expensive houses, the latest planning application offers no affordable housing on grounds of non-viability.

So who does this approach suit? The politicians argue that they are giving developers a hard time, it’s just that in the particular case, and it seems in every case, the financial viability is marginal, whilst the developers claim that they are under the cosh despite making record-breaking profits.

So long as the average voter thinks he’s getting something for nothing the system will probably never change. But if we look at the lack of affordable housing being provided, the poor design quality of many new buildings and the lack of community benefits, maybe we will decide it’s time for a more honest approach.

Would a solution be to have a financial reconciliation at the end of the project, once the costs and revenues are known, and charge a tax on the actual figures? Maybe this is something Secretary of State Michael Gove plans to look at, since providing affordable housing logically forms part of the levelling up agenda, and these types of negotiation are unlikely to result in beautiful buildings, which is the government’s stated aim?

Responses to Opinion: Viability Studies – Great for Politicians and Developers, Disastrous for the Community

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Ant Davis

December 24, 2021 at 3:37 pm

The author should know there is already a review mechanism within the NPPF. It should also be noted that the council does not pay for consultants to review viability, this is paid for by the developer.

Viability of town centre brownfield sites takes into account existing use value (often very high particularly with Class E changes) meaning developments are often not as profitable as one would expect.

Overall profitability for housebuilders is more likely to come from separate out of town strategic land promotion and new estate construction. Town centre redevelopment is considerably more complex and bears increased risk, hence various developers pulling out of large central Guildford proposals over the years.

Mr Harrison’s article feeds the negative and common misconception that developers are actively seeking to “pull wool over the eyes” of councils. Quite the opposite, the quantity and quality of information required has never been so high.