Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Remembering Guildford Men Who Fought And Died At The Battle of The Somme

Published on: 1 Jul, 2016

Updated on: 29 Jul, 2023

The Battle of the Somme began this day (July 1) exactly 100 years ago. It was one of the most infamous battles of the First World War and lasted until November 18, 1916. It claimed nearly one million men from both sides, either wounded or killed. The first day of the battle was the worst in the history of the British Army with nearly 60,000 casualties alone. Here, including extracts from DAVID ROSE’s book Great War Britain Guildford Remembering 1914-18 (published by Amberley in 2014, at £12.99), he recalls some of the local men who took part and how the news was received back home.

In June 1916 British and French forces were finalising preparations for another ‘big push’ against the Germans in the area by The Somme River in France. It was largely to help relieve pressure on the French at Verdun, a little further south.

The Somme battlefield.

Ahead of the battle, the German lines were pounded by a huge artillery bombardment. However, it did not destroy the German wire or the well-constructed dug-outs in which the German troops were sheltering.

On the sounds of whistles at 7.30pm on July 1, British and French troops climbed out of their trenches and made their way across No Man’s Land to the German lines – but they were cut down in swathes by the enemy’s machine guns.

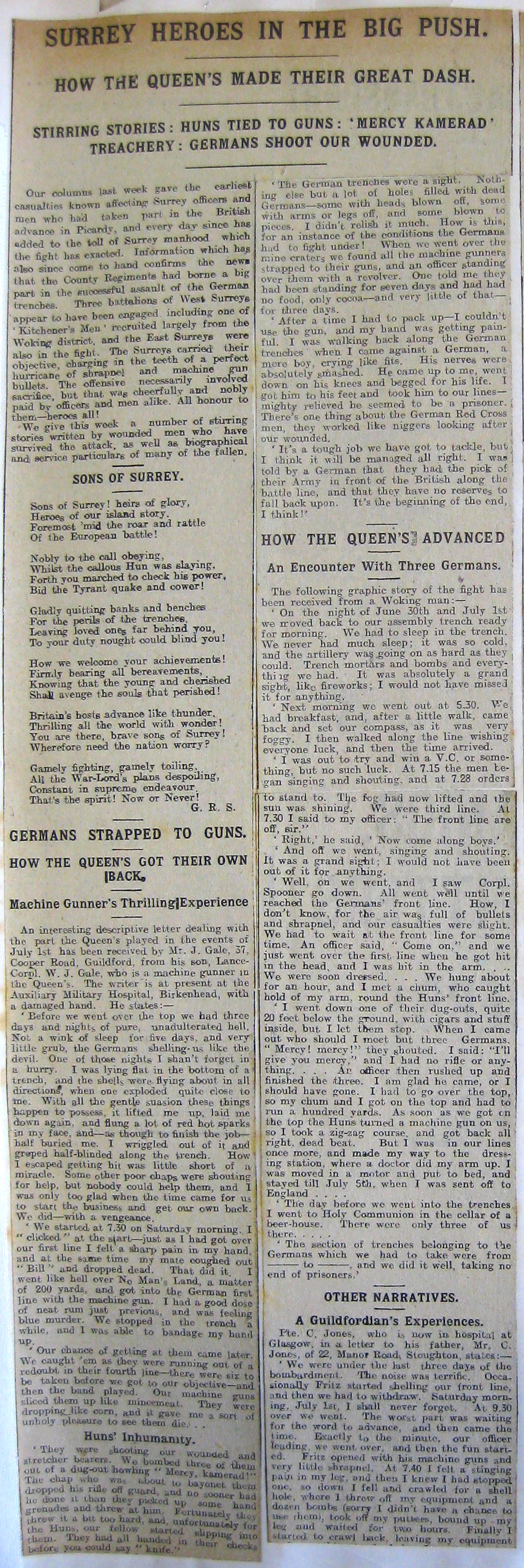

The edition of the Surrey Advertiser soon after the battle began reported: “The nation has been thrilled by the news of the great advance made by the British and French Forces during the past week against the Germans in the Battle of the Somme. We understand at least three battalions of the Queen’s [Royal West Surrey Regiment] were in the advance. Very little definitive news of the actual part they took in the fight has come through, but there seems to be no reason doubting that they were in the thick of it.”

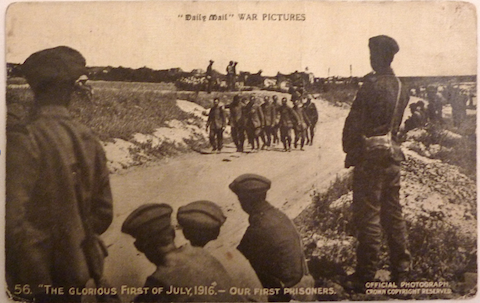

A picture postcard issued by the Daily Mail shortly after the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Indeed they were, and the newspaper published details of a letter written by a wounded NCO from The Queen’s Regiment. “The dawn broke lovely on Saturday morning, the sun shining beautifully. Then at 7.30 exactly our guns started firing farther back. The whistle went and we were out of our trenches and across No Man’s Land in a jiffy. A lot of Germans put up their hands and said: ‘Mercy, Comrade.’ Did we give mercy? Oh! No, they got the bayonet instead. We went through them right and left, turned back and then through them again. If that is Somme battle, I don’t want any more of it.”

Cutting from the Surrey Advertiser. Courtesy of the Guildford Institute. Click on the image to enlarge.

Reports in the following week’s edition of the local press gave an indication of the reality of what had happened, with headlines proclaiming: ‘Ninety officers killed, wounded and missing’ and ‘Heavy casualties among the NCOs and men’; along with long lists of casualties and short biographical details of officers who had died.

Lieut Reginald Oakley – killed in July, 1916.

One of those was Second-Lieutenant Reginald Oakley, of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He was the son of the Surrey Advertiser’s editor, William Oakley.

The report stated Oakley was killed on July 1, the same day as his friend Second-Lieutenant Dandridge, and that he was educated at the Royal Grammar School, where he was in the officer training corps.

He joined the 1/5th Battalion of The Queen’s Regiment the day after war was declared and proceeded with the battalion to India in October 1914.

A year later he returned to take up a commission in the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

He made a special application to be sent to the front and went out full of hope and confidence about a month before his death. His “frank and sunny disposition” made him popular with all. Before he enlisted he was a journalist with the Surrey Advertiser.

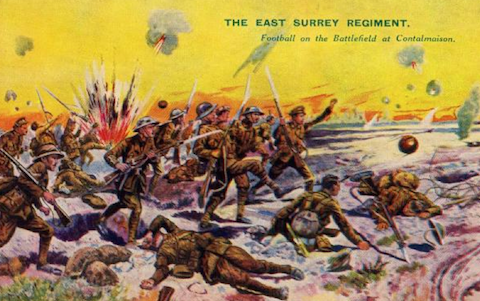

A picture postcard depicting the scene as men from the East Surrey Regiment kicked footballs as they advanced over No Man’s Land.

An early version of the famous story of footballs being kicked by men of the East Surrey Regiment as they made their way across No Man’s Land on the first day of the Battle of the Somme was published in the Surrey Advertiser in mid-July 1916. It read: “Was there anything ever like it? Men playing a game against death!

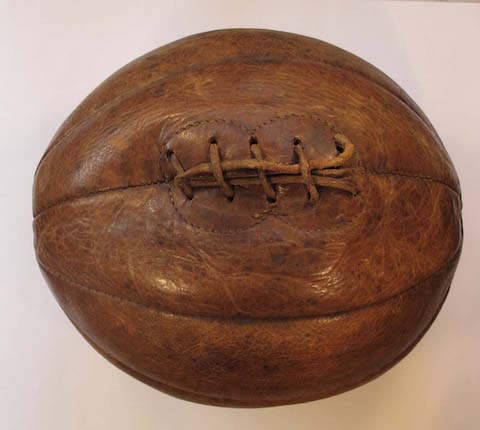

“The officer who provided the four footballs was Captain Wilfred P Nevill, and was related to Mr Ralph Nevill, of Guildford. The gallant officer – he was only twenty-two – was killed early, but two of the footballs reached the German trenches and were subsequently recovered. One was yesterday handed into the keeping of Colonel Treeby at the depot of the East Surrey Regiment, and will be among the most cherished relics of the war.”

This was reputedly one of the footballs. It was an exhibit at the Surrey Infantry Museum at Clandon Park, but was lost in the fire there in 2015.

The Battle of the Somme also claimed the lives of two Guildford brothers Tom and Percy Parson – in the space of seven days. They lived at The Valley, St Catherine’s Village. Private Thomas Parsons, The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, had enlisted at Stoughton Barracks soon after the outbreak of war. He served with the 6th (service) battalion taking part in the Battle of Loos in June 1915, remaining in the front line until November.

Sgt Percy Parsons.

Sergeant Percy Parsons, Royal Field Artillery, enlisted soon after his younger brother, deciding to be a gunner rather than an infantryman. He also fought in the Battle of Loos. In 1916 took part in the week-long shelling of the German lines ahead of the start of the Battle of the Somme.

With Tom billeted in a village alongside the main road to Amiens waiting for orders, and Percy, with his gun battery near Albert, it meant they were only a mile or so apart, although neither would have known.

On July 2, Tom‘s battalion was ordered to continue the attacks across ‘Mash’ valley (so named with army humour to accompany ‘Sausage’ valley to the south) and take the village of Ovillers.

The plan was for a night attack in the early hours of July 3. Percy’s unit was ordered to help in the preparatory barrage for his brother’s division. This commenced at 2.15am. Percy would not have known that the shells he was firing would be assisting his younger brother’s front.

Pte Tom Parsons.

Tom probably found that the darkness made the battle even more frightening, making it impossible to see where the next danger might be coming from, while his officers and NCOs would be struggling to command and navigate across the 500 yards of No Man’s Land between them and the German trenches.

As if all that were not enough, it was raining and there was a thunderstorm to the southeast. It was expected that simultaneous attacks on the flanks of Tom’s battalion, left and right, would suppress German redoubts that contained many machine-gun posts.

In the event, the attack on the left was postponed at the last moment allowing machine gunners to fire on Tom and his comrades unhindered.

Only eight Queensmen reached the German wire.

By 9am it was all over, the attack had failed. The 12th Division had suffered 2,400 casualties. The 6th Queen’s, the battalion of volunteers that had enlisted at Guildford, had suffered over 300 casualties.

Many of those were “missing, believed killed“ and would never have a known grave. One of those was Tom Parsons.

Meanwhile, Percy continued to fight on the artillery firing line just a mile away in front of La Boiselle. He was killed on 10 July, while sleeping in a trench. He is buried at Bapaume Post Military Cemetery, Albert.

Pte Tom Parsons’ medals and bronze death plaque.

A story that has been passed down among members of the Parsons family is that a younger brother, who was aged just 14, then tried to be enlisted. His mother, Fanny, evidently managed to stop him going off to war.

It is also remembered that after the death of her two sons, she woke one night with a strong premonition that they had been killed.

Footage was taken of aspects of the Battle of the Somme and screened in cinemas across Britain shortly afterwards. Mrs Parsons went to see this in a Guildford cinema and recognised her son Percy loading artillery shells with other soldiers. It must have been heartbreaking for her.

Tom and Percy Parsons’ mother, Fanny, with her daughter Minnie, at Percy’s grave. Picture courtesy of Stacey Greenfield.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

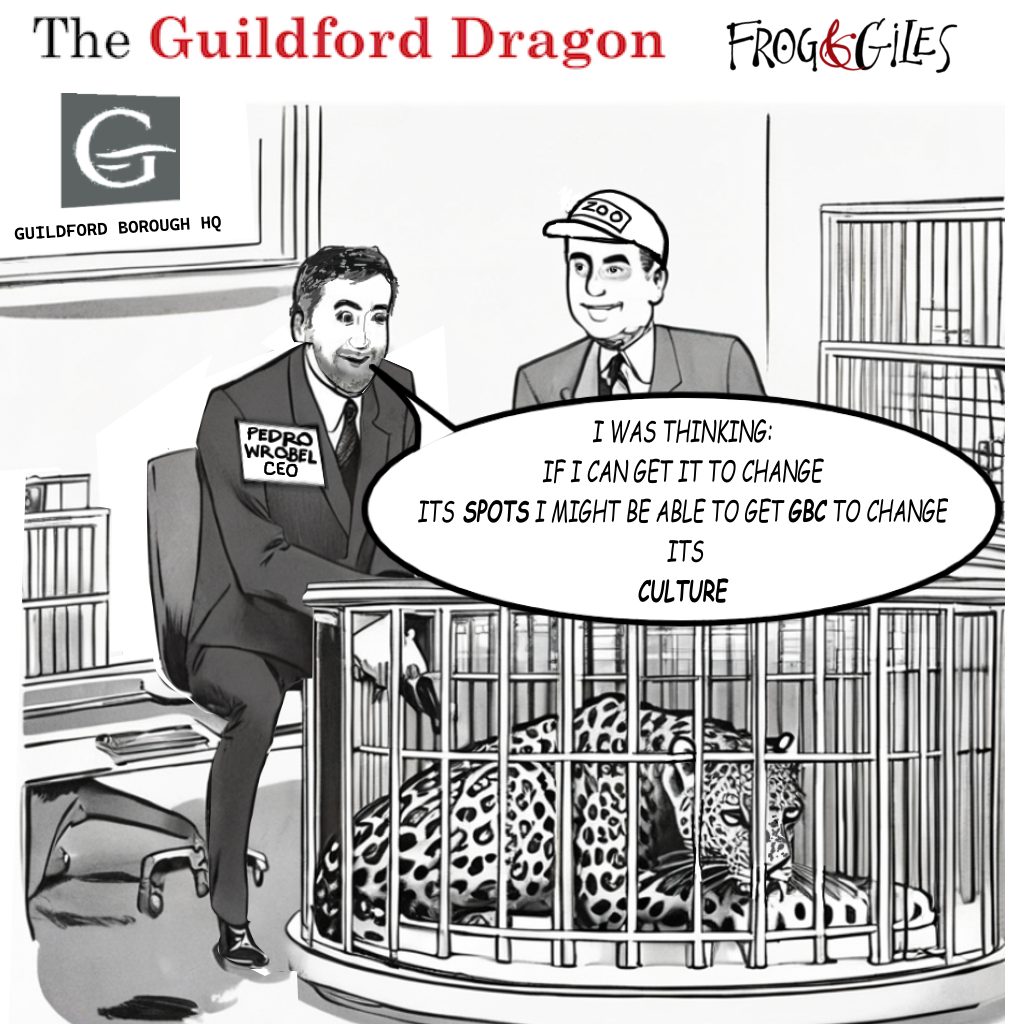

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments