Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

The Brooklands Air Raid, September 4, 1940, 80th Anniversary

Published on: 4 Sep, 2020

Updated on: 4 Oct, 2020

By Frank Phillipson

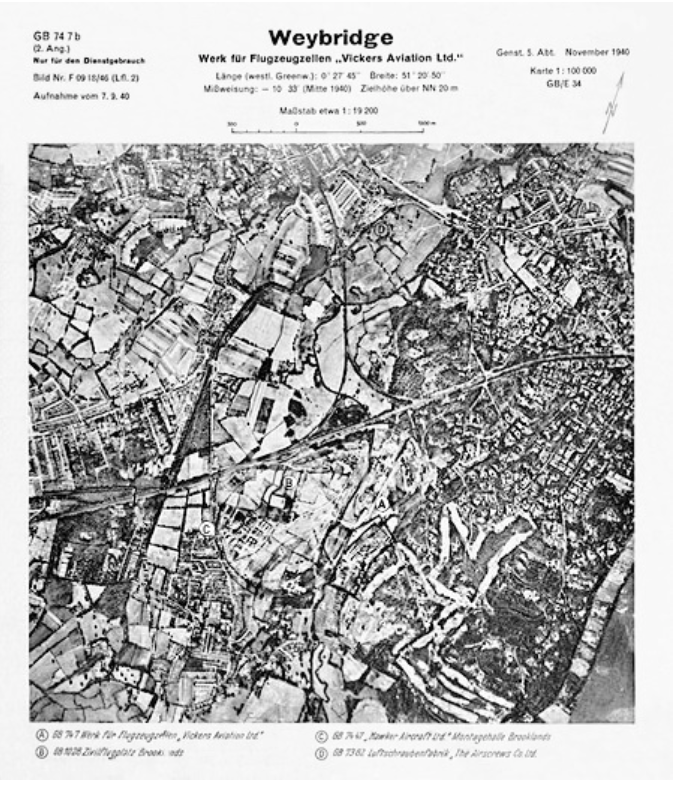

September 4, this year (2020) marks the 80th anniversary of the daring German 1940 daylight raid on the Vickers Armstrong aircraft factory at Brooklands, Weybridge.

It was by far the most deadly attack of the Second World War in the local area with nearly 90 fatalities and hundreds of injured. Considerable damage was caused to the aircraft factory and production of Wellington bombers was seriously affected.

This is a revised article that was previously published in The Guildford Dragon NEWS. It concludes with some unique eye-witness accounts of those who visited the Horsley crash sites and some gruesome ‘souvenirs’ that were gathered up and shown around during the weeks that followed.

In the Walton and Weybridge Urban District Council records, the air raid on the Vickers Armstrong aircraft factory at Brooklands on September 4, 1940, was noted as the fifth air raid within the council’s boundaries since the war began. The first raid had taken place on July 24 and by November 19 the number of raids had reached forty-six. But the Brooklands raid was to cause the greatest number of casualties.

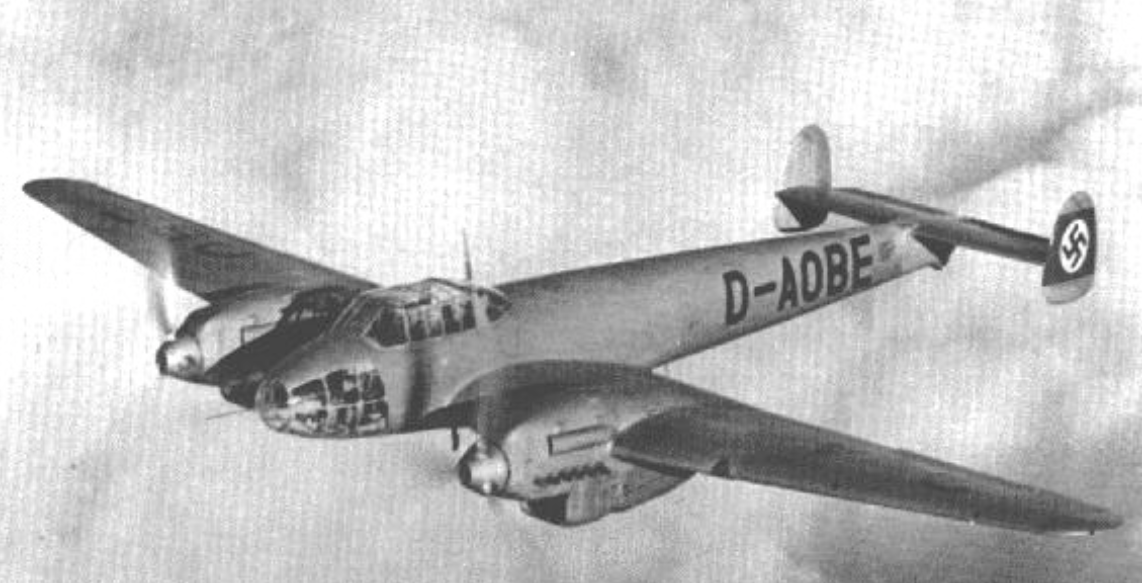

Just after midday, there were a number of Luftwaffe bomber formations already attacking targets in Kent. At the same time a large force of twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf110 fighters and fighter/bombers crossed the English Channel and then flew westwards along the south coast. With the RAF attacking them all the way, they were eventually dispersed in the Horsham area having flown inland from Worthing.

Masked by this larger force, 13 Bf110 fighter/bombers of Erprobungsgruppe 210 (EprGr.210) (specialists in shallow dive, pin point attacks) closely escorted by about 25 Bf110 fighters of V Gruppe, Lehrgeschwader 1 (V/LG1), avoided detection and headed further west and then north.

There had been 14 Bf110s of EprGr.210 but their leader, Hauptmann Hans von Boltenstern, had carried out a manoeuvre with insufficient height and had crashed into the sea off Worthing. The formation would have been flying at low level over the sea hoping to avoid being picked up by British radar.

Climbing as they flew north over the land, they passed over Guildford just after 1pm at 6,000ft. They then flew in an east-north-easterly direction along the railway line towards Clandon and Effingham Junction to Cobham.

Twelve-year-old Peter Brewer was in Ripley school playground when he and few others heard a roar and saw the German aircraft passing overhead.

Schoolboy Ron Arnold was on bus going to a woodwork class at a school in Send (Ripley school not having a woodworking classroom), when the bus stopped just outside Ripley as the German aircraft passed overhead with the bus crew getting the passengers to take cover by lying down in a ditch beside the road.

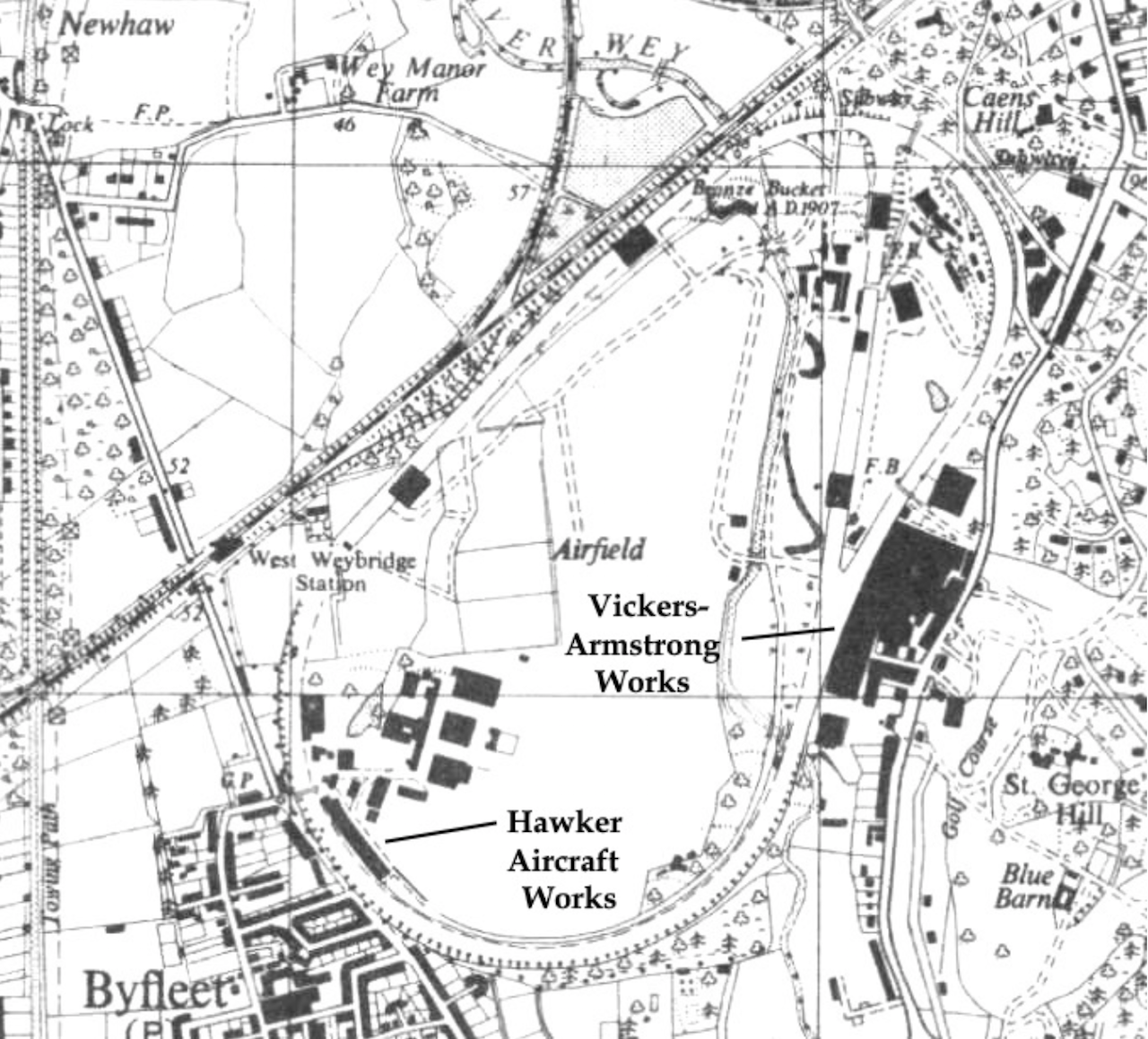

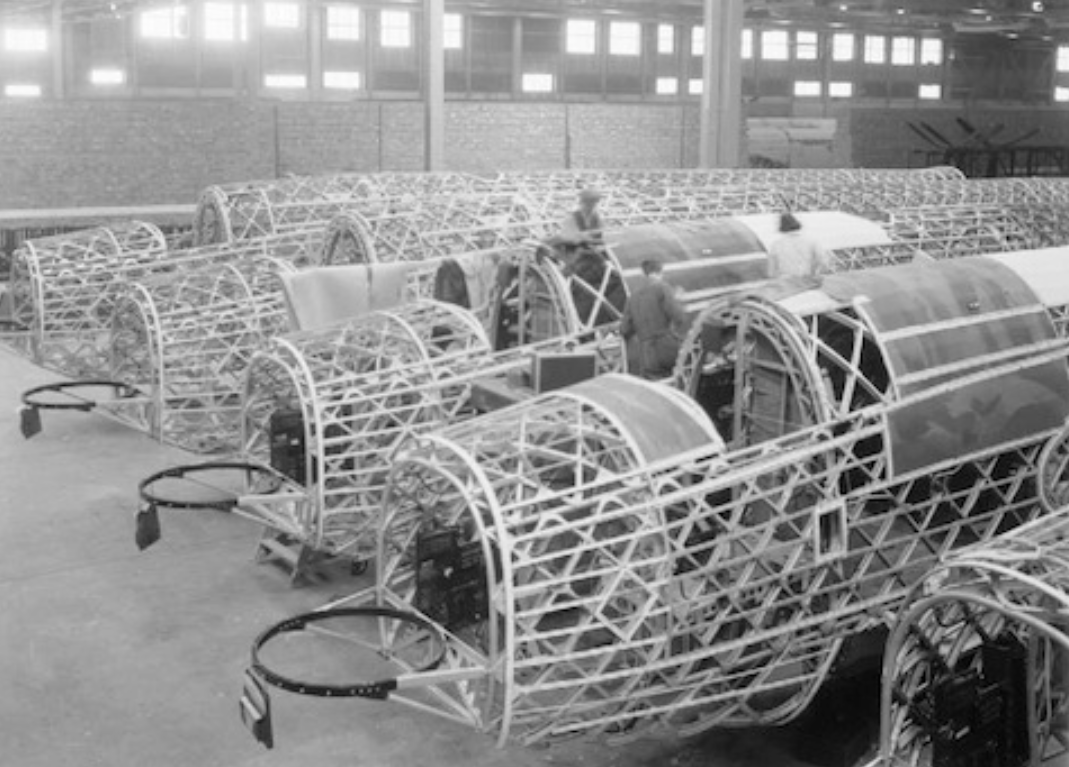

Now the enemy aircraft were approaching their intended target; the Vickers Armstrong aircraft factory at Brooklands which produced Wellington bombers. One of the EprGr.210 pilots, Unteroffizier Balthasar Aretz, recorded in his logbook that the target was an “airfield and works near Brooklands, Vickers Wellington”.

That the Hawker aircraft factory at the south-western end of the Brooklands race track site, that produced Hurricane fighters, was not targeted might seem strange given the Luftwaffe’s aim at the time was to destroy as many British fighters as possible.

It has been suggested that the Vickers factory was attacked to try to reduce the numbers of Wellington bombers that were then bombing German invasion barges gathering in French and Low Country ports. Another theory is that it was Wellingtons, amongst other types, which carried out the first British bombing raid on Berlin on August 25, 1940 which angered Goering who had promised the German people that this would never happen.

Brooklands was protected by heavy and light anti-aircraft guns and Parachute and Cable (PAC) devices that could be launched up into the path of any low-flying aircraft. Brooklands at this time did not have the protection of barrage balloons (they arrived two days after the raid!).

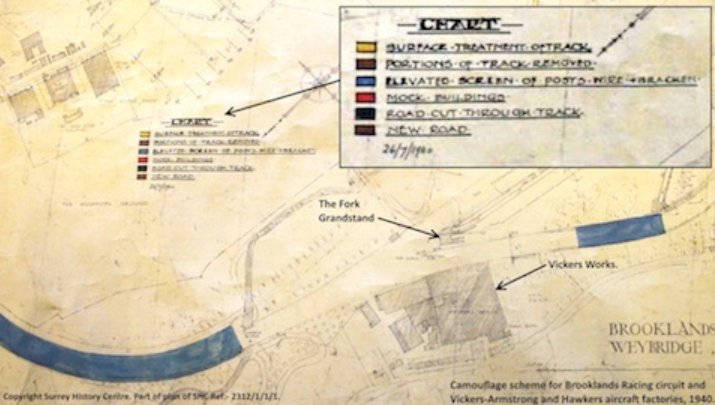

The site was camouflaged with paint, netting and dummy houses. What could not be disguised was the main railway line running along the northern boundary with its distinctive ‘Y’ junction of the line running north-westwards to Chertsey.

Camouflage scheme for Brooklands Racing circuit and Vickers-Armstrong aircraft factory. Reproduced by permission of Surrey History Centre, SHC Ref: 2312/1/1/1. Copyright of Surrey History Centre. www.surreycc.gov.uk/surreyhistorycentre

As it was a fine day many workers were outside during their lunch break. No air-raid warning was sounded as Fighter Command’s plotting system had been overwhelmed by the sheer number of raids and the aircraft attacking Brooklands had not yet been plotted from Observer Corps reports. There was said to have been a spotter on the roof of the factory but he had been unable to see the approaching aircraft because the sun was so bright.

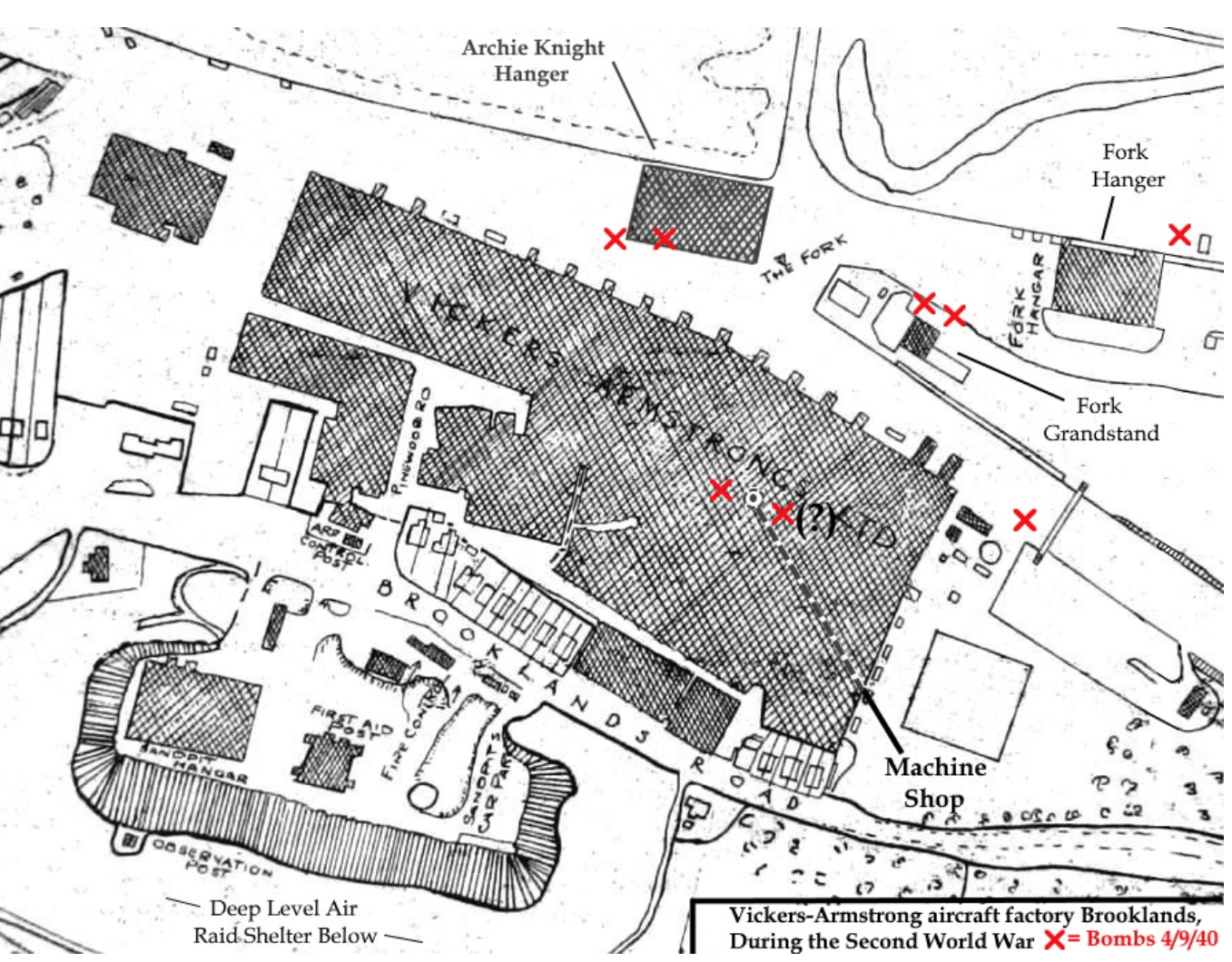

Vickers-Armstrong aircraft factory, Brooklands during Second World War. Photo courtesy of Brooklands Museum.

EprGr.210 split in two with one group attacking from the south and the other from the east. At 1.14pm they dived in on their low-level pinpoint attack, opening fire with their cannon and machine-guns. After each aircraft had dropped its two 500Kg bombs they flew off, initially, north-westwards. They then escaped at speed and at low-level back to France with no losses to any of the 13 aircraft.

Peter Brewer, still in the playground at Ripley, heard the sounds of the attack on Brooklands. He says “The younger pupils went into the school’s air-raid shelter, but we stood outside. Then there was silence.”

See also: I Was Rooted to the Spot When the Bombers Flew Low Overhead

At Brooklands, caught off guard, no one was in air-raid shelters and the defences failed to come into action (one source says that at least one Anti-Aircraft gun opened fire).

Bombs hit a pre-war motor-racing grandstand (The Fork Grandstand) and a repair hanger (the Archie Knight hanger). An air-raid shelter where a number of women were eating their lunches received a direct hit killing them all.

The main damage and loss of life was caused by a bomb that crashed through the roof of the machine shop and then penetrated through the light reinforced concrete first floor before exploding on top of a heavy press in the machine-shop itself. This was close to the time clock and killed many who were just waiting to clock on. Many workers sitting at their benches eating their lunch were killed and injured by flying glass and metal as well as tools and concrete scattered by the blast.

Vickers-Armstrong aircraft factory, Brooklands during Second World War. Plan courtesy of Brooklands Museum.

The general view about the main damage caused to the machine shop has been that “the bomb” dropped through the first-floor workshop and exploded on top of a press. However, in the RAF aerial photos taken on the same afternoon as the attack, a number of bombs that dropped on open ground show the twin bomb craters. This ties in with the two 500Kg bombs that were dropped simultaneously from the under-fuselage mounts on the Bf110’s. It is therefore possible that there was a second bomb that detonated in the machine shop building and that this wasn’t realised due to the complete destruction and debris that resulted.

In one hanger the workers there were lucky as, only the week before, wire chicken mesh had been put up under the glass in the roof. In the other hangers they were still waiting for it to be fitted and many of the fatal casualties were caused by large pieces of flying glass. One estimate of bombing casualties suggested that up to 80% of those killed and injured in industrial buildings were caused by flying glass.

In all, four or five bombs hit buildings in the Vickers works with other bombs dropping outside hangars causing additional damage. Other bombs fell wide of the target some landing on St George’s Hill south of the factory.

Eve Freaks had just left the canteen, clocked in and was sitting at her bench on the first-floor workshop above the machine shop about to start work. Suddenly there was the sound of bombs dropping and exploding. Electricity arced across the workshop and there was noise and screams everywhere. All hell broke loose. The roof went and “all you could see above you was a German plane with a Swastika on it”. The scene in the factory was utter chaos.

She knew she had to get out of there and ran to the top of the stairs and waited her turn as others descended. As she waited, she “wondered what it would be like up there (heaven) as she thought she was going to die”.

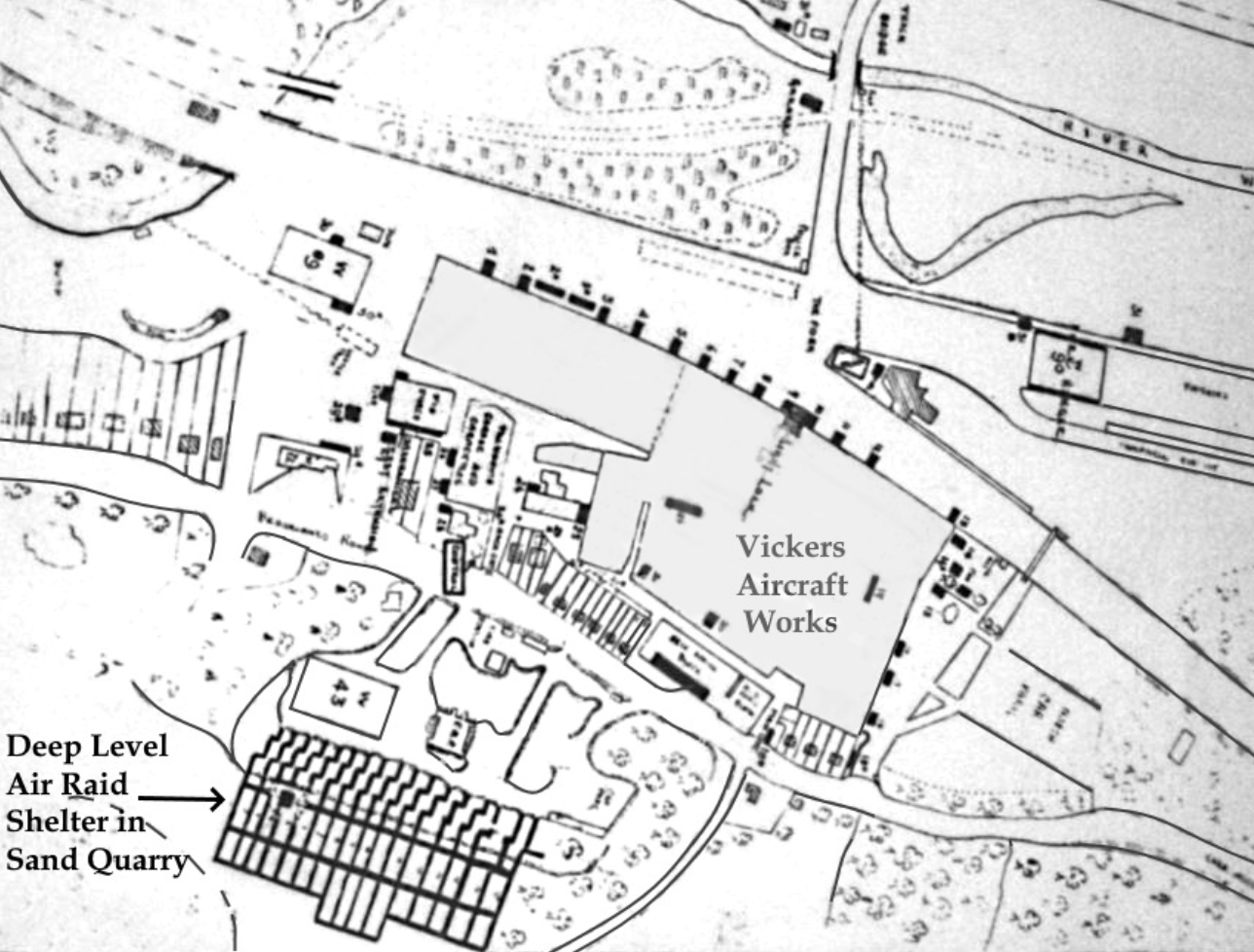

Getting halfway down the stairs there was a man lying flat and blocking the way. They managed to get round him and down and then out. She then had to make her way across Brooklands Road to the deep air-raid shelters that had been built into the sides of a former quarry.

As she ran, she could hear the planes diving down and the rat-tat-tat of their machine guns. She ran for her life and finally made it into the shelter. They waited there for two or three hours while they recovered all the dead and injured. When they were allowed to leave, they were told “not to look at the factory we had got out of because we would be so shocked”.

One worker, who decided to play one more round of cards before the end of the lunch break, but whose other workmates had largely left to return to work, found after the raid that they had all been killed back at their work benches.

A senior aircraft inspector, Bill Hayes, was outside the buildings with his colleague Tug Wilson. As the first bomb exploded, he recalls: “I was dazed and bleeding and was almost on my feet when two more bombs fell”. These landed in front of what was known as the “Archie Knight” repair hanger. “Suddenly the air became like night, full of black dust and smoke”. He lost touch with his friend but managed to take cover by diving between a sandbag wall and the wall of the machine shop.

When a man in panic broke cover from where he was laying, Bill grabbed hold of him and held him down just as a line of bullets zig zagged across the concrete just missing the man’s feet. The man then broke free and ran off.

Pulling himself out from under a sliding door that had fallen over him, Bill went into the machine shop. He was greeted by the sight of the bodies of two men he knew and who had been outside with him before the bombing. One in a terrible condition lay dead by Bill’s desk while the other had been crushed between two Wellington fuselages that had been blown together.

Joe Pennock had just returned to the air frame he was working on after getting some pencils from Renie Colman in the office, and had taken a half a crown from his pocket. “I spun it up in the air to decide whether to start working on the top of the plane or the bottom. I never caught it! The first bomb dropped, it struck one of the large steel presses. The blast went out sideways killing not only Renie but two young lads, Dollymore and Gunner, (I cannot remember their first names) who were due to leave that week and join the Royal Navy”.

“One of my work mates (Frank Drewitt) had his heel blown off, so I took him over to the First Aid Station that was situated in the air-raid shelters across Brooklands Road. It was then someone told me that I had blood running down my face from a wound on my head. After being treated I returned to see if I could find my wife but was told to go home as all staff not injured had been sent home. I arrived home to find my wife there uninjured.

“I will always remember the cars left in the car park for months, their owners killed in the bombing. Also, the Canadian troops sent to clear up the damage caused nearly as much mess as the bombs did.”

Marjorie Moran was 14 years old and had just left school that summer. She started work at Vickers employed in the Wing shop office as a clerk. At about 12.30pm she and her friend went for their usual lunchtime walk. They came back into the factory at about 1.20pm and she started making her way to the office. However, one of the men working on the Wing Gallery stopped her to ask about his insurance card. While they were talking, they heard a noise, and the man said he thought it was odd that the machine shop was starting early.

Suddenly there was a terrific explosion followed by another, and he pushed her towards a spiral staircase which led to the finished parts stores. On the way she lost her shoe and went back for it, fortunately as it turned out. There were sandbags at the bottom of the staircase and just as she nearly reached them, they were blown up with by an explosion and she was covered in debris.

She ran out into the yard with broken glass everywhere and it was lucky that she had gone back for her shoe. All this time the machine-guns were firing from the attacking planes. On the far side of the road by the factory there were deep shelters cut into the hillside.

Location of Deep Level Air-Raid Shelter in a cliff of the old sand quarry. Courtesy of Brooklands Museum.

She says “I must have run across to them, but to this day I cannot remember a thing about that. All I remember is coming to, my overalls covered in blood and sand, and it wasn’t my blood”.

At school two miles away was nine-year-old Jim Burrell. He recalled that he “arrived home followed shortly after by my aunt and sister who both worked at the Vickers factory”. His 16-year-old sister had a horrendous story to tell. When the raid started, she, along with others, ran for cover and had to dive to the ground because they were being machine-gunned by the aircraft. As they did so his sister was aware that a soldier had fallen on top of her – and acted like a shield. Afterwards, when she was helped to her feet by someone else, she discovered that the soldier was dead.

Denis Jacobs was on his way back to work at Vickers with a friend called Charlie Hull and had just cycled over Plough Bridge at Byfleet when Charlie pointed out to him several aircraft flying over St George’s Hill golf course from the Cobham direction. Within seconds of this, the bombs started to fall.

Marjorie Ellerby (later Smith) took one of her friends who was unwell to the sick bay and because of this was not in the vicinity of the factory explosion and escaped injury.

In just a few minutes the raid on Brooklands was all over. At least 87 people were killed and 419 injured.

At this moment the General Manager and the management of Vickers started to take control of the situation. This was despite the fact that the Industrial ARP Officer of the Works already had a plan in place to deal with any raid on the factory. This had been worked out with the ARP Controller for the Walton and Weybridge UDC area in May 1940 and included a direct line (Walton 2231) from the factory to the ARP Report Centre which the General Manager did not know about. If it had been used, ambulances could have been sent that would have probably met all the needs at the incident and whose drivers knew which hospitals had been designated to receive the casualties.

Instead, calls were made to “all and sundry to send help”. The drivers of the ambulances that were summoned by this method did not know which were the most suitable hospitals to take the injured to. There was also a complaint that the police failed to establish any traffic control which led to further delay. Further congestion was caused by large numbers of undesignated private cars of Vickers staff being used to transport sitting cases.

Walton Hospital with 16 beds received 70 stretcher cases. Instead of taking patients to another hospital when that one proved full, the ambulance men “dumped their cases in the drive or at the Aid Post and went away”. Fortunately, the weather was warm and dry.

St Nicholas Hospital, Pyrford (later known as the Rowley Bristow Orthopaedic Hospital) with 100 beds did not receive a single case. The County Medical Services could have taken in all the casualties at Botley’s Park Hospital.

Eventually the injured were taken to hospitals at Walton, Weybridge, Botley’s Park, Brookwood, Guildford, the Schiff House of Recovery Cobham “and perhaps other hospitals”.

Botley’s Park War Emergency Hospital, (later St. Peter’s). Patients in beds on veranda. Courtesy of Chertsey Museum.

The ARP Sub-Controller in the Walton and Weybridge UDC area Report Centre did not have any information about the amount of damage or the number of casualties at the incident apart from knowing that some ambulances had been summoned. Leaving his deputy in charge he went to the scene.

At the Vickers main gates there should have been a police Incident Officer in a white coat together with a chequered flag. The Sub-Controller could see none and every police officer or soldier he asked as to his whereabouts didn’t know either. He eventually found the Works ARP officer who took him the Vickers’ First Aid Post.

Having assessed the situation, the Sub-Controller phoned the Report Centre for all available services to be sent and for County mutual assistance to be requested. When all the casualties had been removed and he was leaving the site through the main gates he saw that there now appeared to be the Incident Officer who remarked that no services had reported to him!

In the Vickers factory, ARP rescue teams, aided by factory ARP teams, arrived and started the task of rescuing the injured and removing the dead and “worked magnificently”. However, soldiers trying to help at the scene were said to have impeded rather than helped because there was a lack of efficient officer control. There were plenty of messengers and stretcher bearers with young men aged from 16 to 20 proving to be the best messengers.

The injured were treated by the Aid Posts on site and in almost all cases were given A.T.S (anti-tetanus serum) before being taken to hospital. With a great many seriously injured the doctors on the spot gave 50 to 60 injections of morphine and nearly 40 pints of blood and almost 30 pints of plasma were used.

The First Aid staff of Vickers was highly praised under the leadership of Mr D G Lloyd and Miss V Willsher. Within 30 minutes of the raid, with the exception of a few minor injuries, all 400 casualties had been treated and dressed and many of them were already on their way to hospital.

One problem at two of the Aid Posts was that no extra volunteers were found to take the particulars of each patient. With the overwhelming rush of work, forms were not filled or not filled in fully, which meant that 24 hours later names were still being recorded.

Additionally, with ambulances and stretcher parties being summoned from various locations no accurate record was kept of which hospitals the patients were taken to. It took many hours to finally contact all the places where there were patients from Brooklands.

By 3.30pm all the casualties had been removed from the site to hospitals, mortuaries or First Aid Posts. By about 4.20pm many slightly injured people had been taken home.

Help from a great many doctors was offered but “were really a hindrance rather than an assistance”. Surgical teams from the New Zealand (Army) Hospital (No.1 NZ General Hospital, Pinewood Sanatorium, near Wokingham) and Brookwood (partly a military hospital during the war) were of great value. A neurosurgical team from East Grinstead, a thoracic team from Horton and a shock team from St Thomas’ also assisted in treating the injured. These teams worked until midnight on September 4.

One patient being taken to the mortuary was luckily seen by a doctor who pronounced that he was very much alive. On one corpse, someone had pushed a stray identity card into its armpit which temporarily confused identification.

By September 6, the total casualties numbered about 300 with 64 dead of which at least 20 to 30 were unidentifiable except by circumstantial evidence. A few days later the number of dead was said to be approximately 80 but that this could rise as a number of the casualties had very severe injuries. The number of injured was now about 400.

A final breakdown in September 1940 of figures of killed and injured were:

Males killed 75

Females killed 8

Males seriously injured 169

Females seriously injured 7

Males slightly injured 204

Females slightly injured 39

Total 500

The local mortuary was unable to cope with the number of dead bodies, so Mount Felix Hall in Weybridge was put into temporary use.

Four bodies were never identified and little was found of the girls who were killed by the bomb that fell on the shelter where they were sitting. At 2.30pm on September 9, one identified but unclaimed body and four unidentified bodies were buried at Burvale Cemetery, Hersham. A joint ceremony was conducted by the Reverends Brittain, Job and Tritton which was attended by the relatives of unidentified persons, Council officials and staff, Fire Services, First Aid Personnel, representatives from Vickers-Armstrong and Surrey Constabulary.

It is believed that subsequently, each of the next of kin to those who were killed, were each awarded £300.

The damage at Vickers resulted in the estimated loss of two months output (32 Wellingtons). Many parts of the factory were dispersed to numerous other buildings in the area including part of a film studio and an undertaker’s premises.

In his report analysing the raid of September 12, Mr W H Harris the Clerk of the Council, who was also the Sub-Controller, stated that it was a police officer who was responsible for telephoning around for ambulances. However, he gives no further detail about whether this was on the officer’s own initiative or whether it was an instruction. The report was circulated to all those involved and included copies of letters sent to the General Manager of Vickers-Armstrong and to the Superintendent of the Weybridge police, detailing the procedures they should follow in any future incident.

The raid was said to have caused a serious drop in morale with the workers asking why they had been let down with no warning to them or to the soldiers manning the anti-aircraft guns. The Minister of Aircraft Production, Lord Beaverbrook, fired off a memo to the Prime Minister demanding to know why his factory hadn’t been protected.

In answer Fighter Command said that the reporting system had become overwhelmed by the sheer number of plots coming in. It claimed that all the aircraft attacking Brooklands were shot down except for one. In actual fact, none of the 13 aircraft that attacked were shot down. It also said that it had been 234 Squadron (and not 253 Squadron) that had attacked the enemy aircraft in the vicinity!

As a result of the raid, the AA guns were told that, if the reporting and plotting system were to become overwhelmed again, they were to independently open fire on any hostile aircraft they saw.

In the days following the attack, ‘A’ Company of the 1st Canadian Pioneer Battalion, Royal Canadian Engineers were engaged in repairing of the saw tooth glass roof. Having already removed mountains of bomb debris from the plant area they had to rebuild the roof without hindering the machinists, sheet metal workers and assemblers on the factory floor. This included stripping more than 170,000 square yards of plate-glass panels and replacing them with reinforced Rubberoid material in wooden frames.

While EprGr.210 attacked, the Bf110 fighters of V/LG1 flew protective cover above in “Vics” as a local clergyman recalled at the time.

At 1pm, nine Hurricanes of 253 Squadron were ordered to take off from RAF Kenley and patrol above the airfield and over nearby Croydon airfield.

They were led by their acting commander Flight Lieutenant William Cambridge. Leading the squadron southwards and climbing into the sun at 12,000ft he saw enemy aircraft attacking Brooklands to the northwest. He turned the squadron to starboard and dived in on them.

Hawker Hurricane Mk.I “R4118” flying at the Shuttleworth Collection in 2017. Alan Wilson. Wikimedia Commons.

The aircraft they actually engaged were the escort aircraft of V/LG1. Cambridge said in his personal Combat Report that the Bf110s were flying at 6,000ft to 7,000ft in “Vics” of three. They were seemingly caught by surprise as they were not in their circling defensive formation.

Cambridge picked his target and attacked from the side and above firing all his ammunition from 450 yards to point blank range.

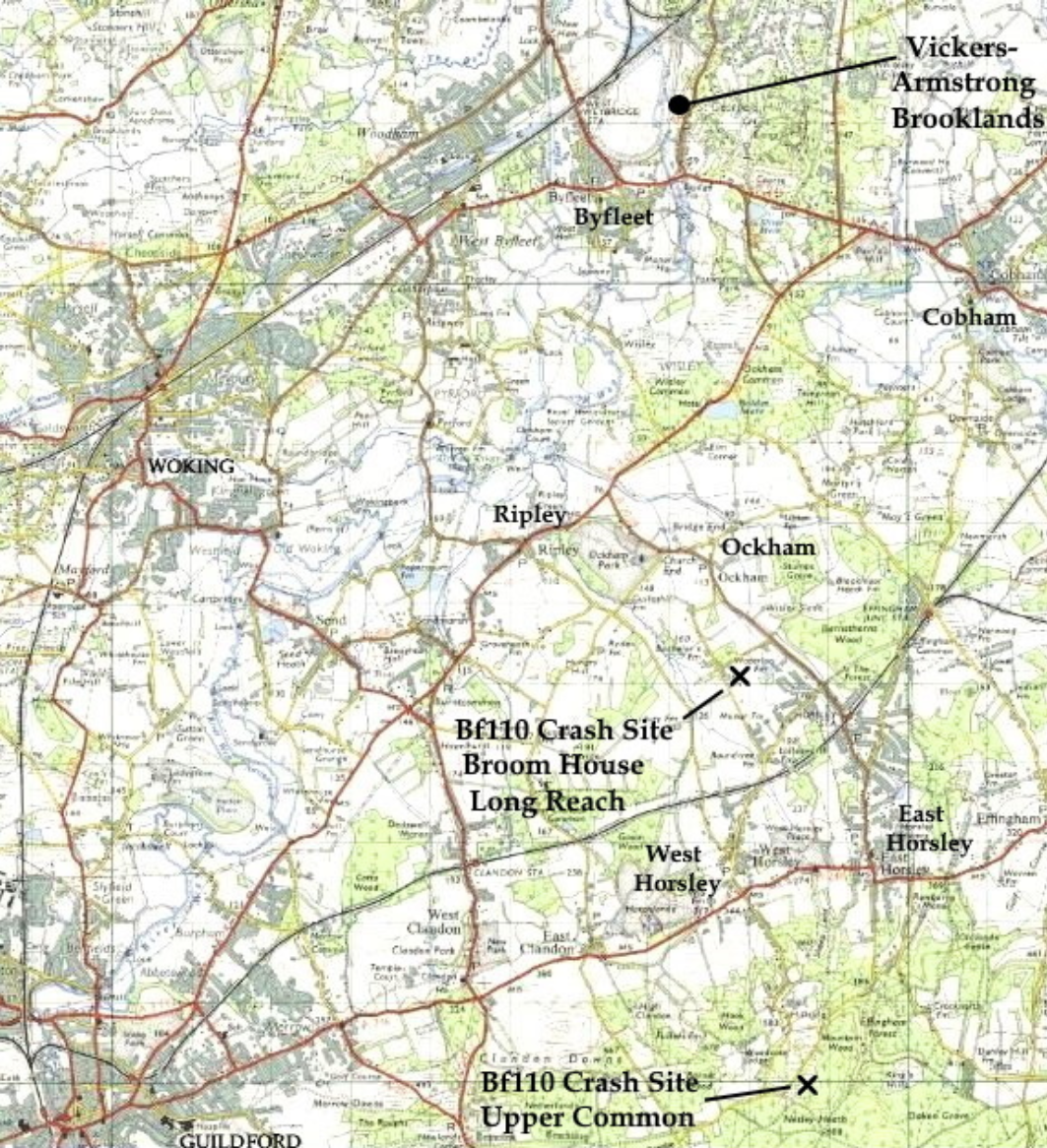

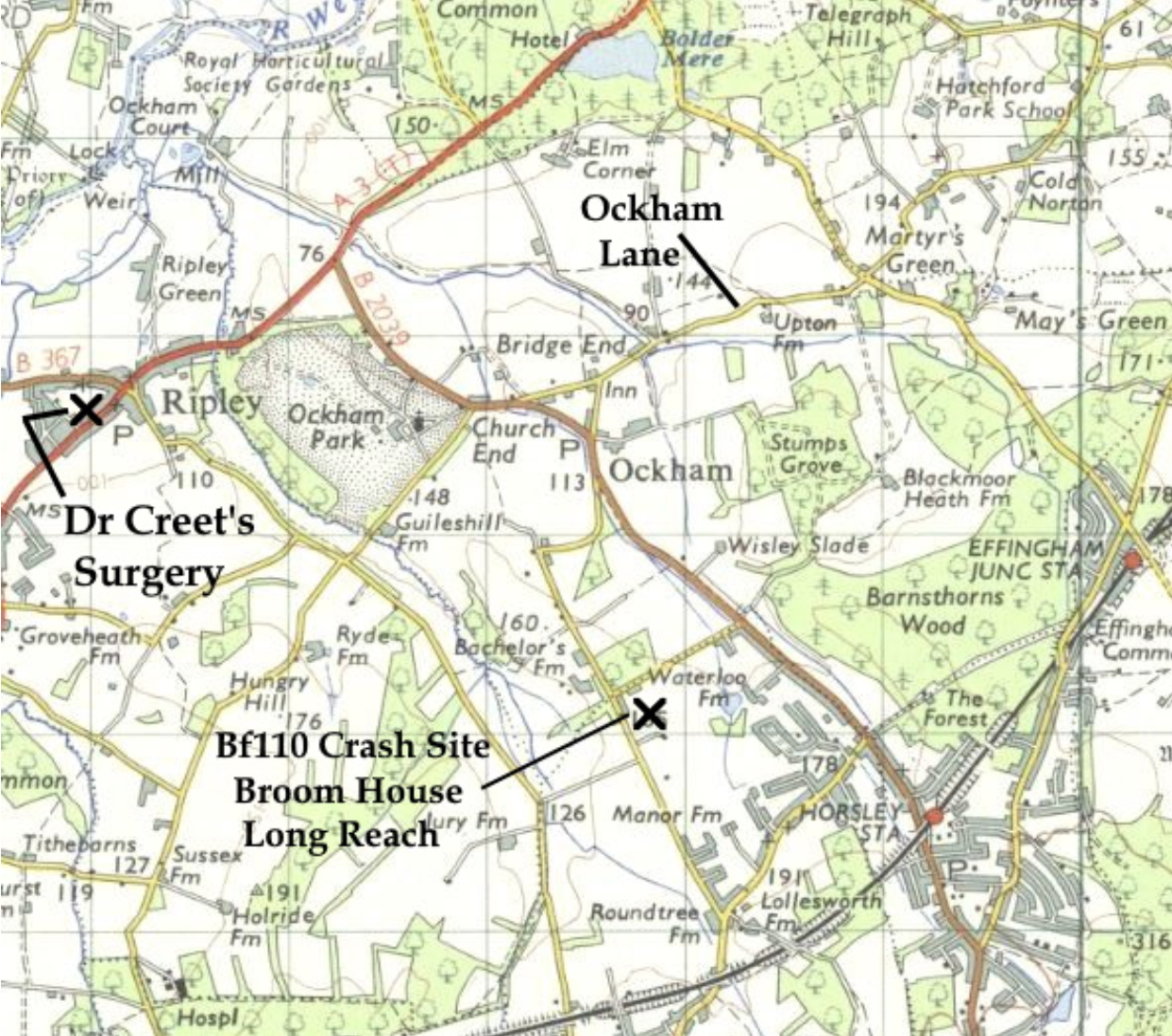

The Bf110’s port engine caught fire and the aircraft stalled, turned to port and dived crashing in flames about 50 yards north of a farmhouse (actually Broom House, Long Reach, West Horsley). Cambridge stated that he had experienced some machine-gun fire from the rear gunner but this had soon been silenced.

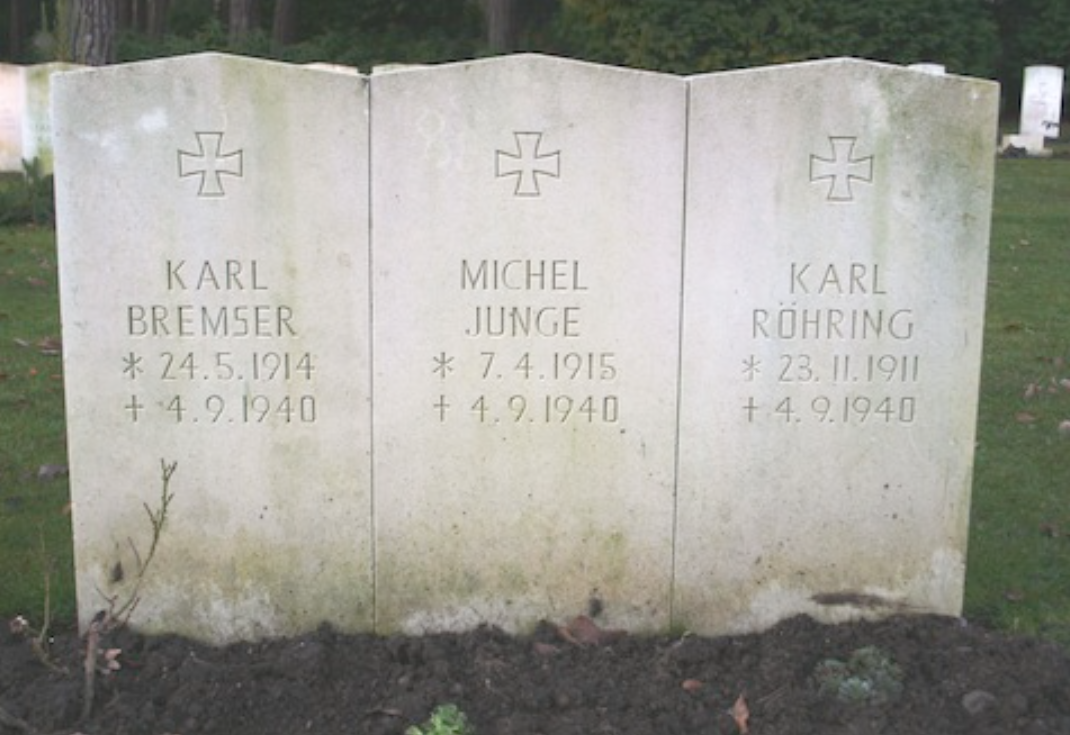

The rear gunner, Unteroffizier, Joachim Jackel, baled out wounded and parachuted down on land south of Ockham Lane near Ockham cricket ground. He was taken prisoner by members of the Home Guard who were gathering in the harvest. The pilot, Feldwebel Karl Rohring, was killed in the crash where the aircraft burned and exploded.

While still in the playground, Peter Brewer recalls: “We then saw a Messerschmitt being chased by a Hurricane that shot at it and we saw some white smoke. It turned left and went into a shallow glide and a man bailed out. We (then) went back to class as if nothing had happened.” He later went to see this crash site being guarded by Canadian troops. He says one of them took his bike and went off for a ride for about an hour!

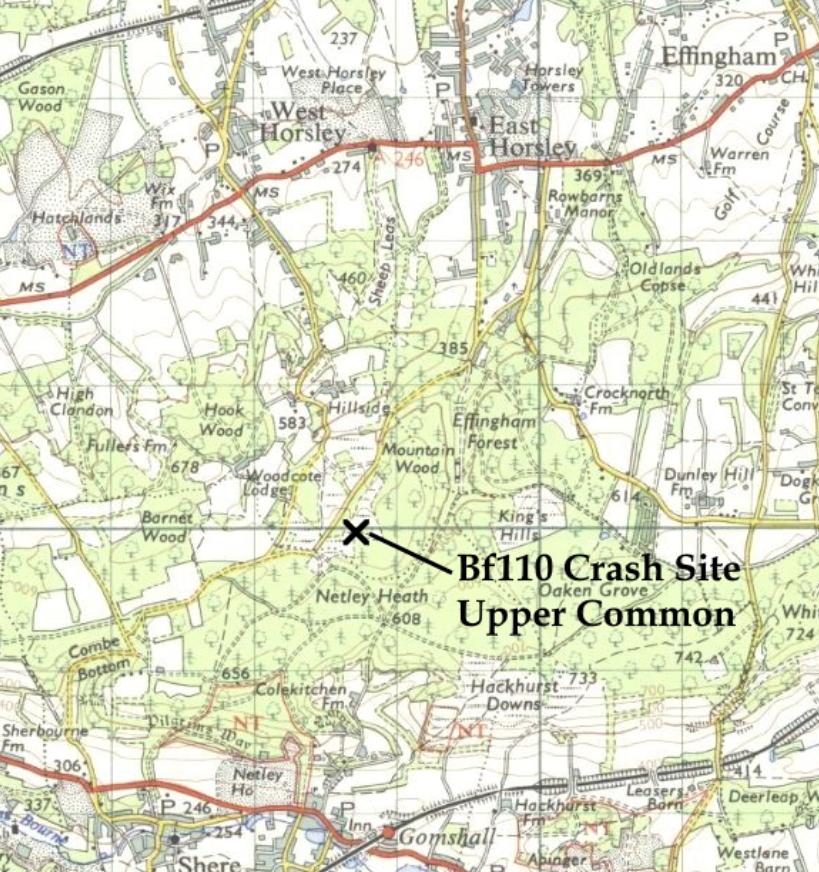

253 Squadron shot down another Bf110 from V/LG1, which crashed and burned at Upper Common, Netley Heath, West Horsley, on the North Downs. The pilot, Oberleutnant Michel Junge, and his gunner, Unteroffizier Karl Bremser, were both killed in the crash.

The rest of V/LG1 escaped towards the coast. However, two more of their aircraft failed to return, and with no record of them crashing on land, must presumably have been lost in the English Channel.

The combat reports of the 253 Squadron pilots described the Bf110s as “Messerschmitt Jaguars”. The Messerschmitt Jaguar was in fact a Messerschmitt Bf162. To meet a German Air Ministry specification for a fast light bomber the Bf110 design was modified with a glazed nose for a bomb aimer. Three prototypes were built in 1937 but it lost out to the new Junkers Ju88 and the Henschel Hs127.

However, as a disinformation tactic, images of the Bf162 labelled as the Messerschmitt Jaguar were widely used in the German press. It can therefore be seen where the 253 Squadron might have found their reference to this type.

At Bridge End Farm, Ockham, Bill Shere, the farmer’s son who was 12 years old at the time, watched as the Bf110s dive down on Brooklands and saw smoke rising from the attack. He also saw the Hurricanes descend on the German fighters and Joachim Jackel in his parachute seeming to “rush down” and land.

Cecil Bradford, the gardener of Bridge End House and a member of the Ockham Home Guard, was the first to get to the German airmen. William Gregory, the estate manager at Ockham Park, administered first aid to the wounded man.

Canadian troops from the Ockham Park Estate (where they were stationed) also rushed to the downed airman and it was said they wanted to “finish him off”. However, despite this, none of the airmen were killed by Canadian soldiers.

Eventually, Jackel was taken by the Canadians together with PC Parrott of Ripley, in a car to the surgery of Dr Ralli Creet at Malabar House, opposite the church and school in Ripley High Street. Joan Chandler (nee Hatcher) recalls looking through the school railings and seeing the injured airman brought to the surgery. There was a large crowd present and she says that the man looked petrified.

Ripley High Street South in the 1930s and how it probably was in 1940. The house on the left with the large tile roofed porch was Dr Ralli Creet’s surgery. On the right of the photo is the school railings that Joan Chandler looked through. (Frith 81709). Courtesy and Copyright of Francis Frith.

Jackel had to wait for Dr Creet to return as the doctor had set out for the crash site but been given incorrect directions. The airman had cuts to his face and head, broken both arms, had a bullet wound in one arm and another in his left foot and was suffering from shock. He was said to have been put at ease by the village schoolmaster who spoke German. However, Dr Creet’s assistant was Nurse Paul, an Irish lady who had lost her sweetheart/fiancé in the First World War. She was far from happy in attending to Jackel and was not that gentle when tending and dressing his wounds.

The house in the High Street., Ripley that was Dr Ralli Creet’s surgery Malabar House in 1940. Author.

The doctor described Jackal as being about 22 with some sort of decoration on his tunic and that he sat almost silently all the time he was in the surgery. Dr Creet said that he didn’t seem too upset and that he could speak a little English. The doctor thought that he was a “brave man”.

While Jackel was being treated the crowd grew outside the surgery. When he was carried to a car escorted by the police and military, some women booed and Bev Jackman recalls that many spat on him, which she thought was awful.

Peter Brewer also witnessed the commotion as people gathered outside the doctor’s surgery. He says: “Some Ripley lads who worked at Vickers came up and jeered and said they had been machine-gunned. I recall our headmaster Mr Dixon saying he was ashamed at the people of Ripley who jeered and they should be ashamed as the airman was only doing his duty for his country”.

Jackel’s bullet-holed left boot was picked up and taken around the village to collect donations for a fete being held to raise funds for an air-raid shelter for the local school and also for troop comforts.

Near (the former) Broom House (now demolished) three men had been working about 20 yards from where the aircraft crashed on land adjacent to Waterloo Farm and near to a pre-war campsite. George Hone, G. Finch and E. Jarvis all ducked for cover, but Mr Hone was hit by a fragment but not seriously hurt. They had to remain in cover for half an hour while the aircraft continued to burn and explode.

Edward Cooper, a teenager living in Ripley, was riding his bicycle home along Ockham Road North near Waterloo Farm when an 8in x 3.5in fragment of Perspex from the Bf110 landed on the road in front of him. For many years he used it as a seed tray divider.

A schoolboy, Ken Brown from Waterloo Farm, was one of the first to get to the crash site once the fire had died down. A number of older men had been evacuated to the farm from a home in London. With no guard yet in place, Ken and one of the men, purloined one of the nose machine guns and hid it in a nearby shed. On returning to the crash to “recover” a pair of binoculars hanging from a nearby tree he was caught as he climbed down by a Canadian Army sergeant waiting at the bottom. He had arrived with some of his men to guard the crash site. They roped off the area to prevent collection of more trophies and in case there were any unexploded ammunition or bombs.

The adjacent campsite had been used pre-war by Londoners at weekends and was known locally as “The Camp”. At the time of the crash evacuees had their tents and caravans spread across the campsite.

Maurice Yates, who was eight at the time, lived on the camp site in a caravan where his family had moved to from London. His father in his Home Guard uniform took him over to survey the scene and talked to one of the French-Canadian soldiers who had got there before other Canadian soldiers arrived to guard the site. From his tunic pocket this soldier proudly produced a human ear.

Broom House Messerschmitt Bf110 Prop Blade being held by Simon Parry 1977. Courtesy Simon Parry. Prop blade now displayed at Brooklands Museum. Courtesy Mark Coxhead.

Bill Shere describes the crash site as just a hole (one description is of a 20-foot crater) in the ground with wreckage and the human remains of the pilot strewn all around and in the trees. Edward Cooper said that there was not a lot left of Feldwebel Rohring and that “his (few) remains were removed in a bucket”.

Ken, Maurice and their friends used the crash site as one of their play areas for the rest of the war.

The Bf110 that crashed on Upper Common set light to woodland to which the fire brigade was called to put out. The crash was near a tented encampment of the Canadian West Nova Scotia Regiment. Its war diary records that its soldiers had to guard the wreckage and the dead occupants.

Oscar Muller, who was aged 16 at the time and a pupil at Guildford’s Royal Grammar School, tells of how he and a friend, having heard about the crash, rode up and along the North Downs on their bicycles to Upper Common. It was near dusk when they came across the aircraft remains, guarded by the Canadians.

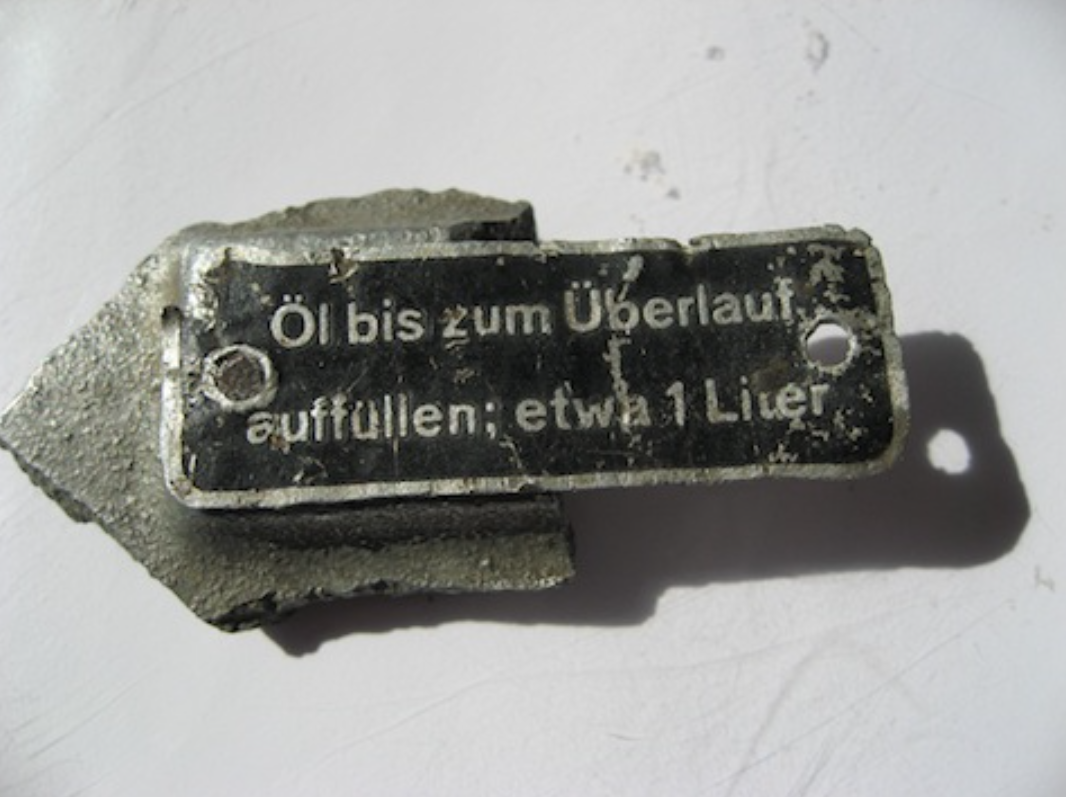

7.92mm ammunition recovered from the Upper Common, Netley Heath Bf110. The cartridge cases appear to have exploded in the fire following the crash causing their torn appearance. Photo courtesy Albert Carter.

One of the soldiers asked if they had come looking for a souvenir of the crash. Using the bayonet on the end of his rifle, he lifted up in front of them the “back bone” of one of the dead airmen. This vividly brought the war home to the two boys.

PC Arthur Bunce recalled that he and PC Bert Bradley were told to go and collect the remains of the crew of the Bf110 that had crashed at Upper Common. Using new sandbags, they gathered up the body parts and took them to the Woking mortuary. Much later they were later asked if they had labelled the bags. They hadn’t and therefore had to return to the mortuary where PC Bunce found the smell so strong that he couldn’t face the task. PC Bradley carried out the labelling by taking a deep breath and rushing in to complete the job one at a time.

Brian Mitchiner, a boy in 1940 living in Netley Gardens, Gomshall, was friendly with the Canadian soldiers. They showed him a finger in a matchbox which they told him came from one of the German airmen.

John Chandler was 10 years of age at the time and lived in Green Dene, Horsley. He says he was shown a piece of skull that had been shaped into a swastika. The bone looked very new and he was also told it came from one of the airmen.

Joy Stevens (nee Harris) was 17 at the time and lived at Hyde Farm, Ockham. At a dance a few days after the crash a German flying helmet was passed around with a piece of skull with skin and hair still inside. She says it was a terribly gruesome.

It seems that all the body parts were recovered by Canadian soldiers. Quite a few local people believed that the airmen had been killed by the soldiers. With the stories about body parts, it would have seemed at the time, to have given some credence to this, especially when you consider the secrecy there was then and with what stories there were, passed on by word of mouth.

Canadian soldiers used parts from the aircraft to make souvenirs including rings, necklaces, cigarette lighters and a variety of other things. Bits of Perspex were made into jewellery.

The very hostile attitude to the German airman and the fact that body parts seem to have been openly shown around doubtlessly reflects the anger towards the enemy. With Britain imminently expecting invasion and air attacks killing civilians and servicemen alike, it is perhaps understandable.

The three dead German airmen were buried with military honours together at Brookwood Military Cemetery. Flight Lieutenant Cambridge was killed two days later when his parachute failed as he baled out over Kent.

Responses to The Brooklands Air Raid, September 4, 1940, 80th Anniversary

Leave a Comment Cancel replyPlease see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear.

Recent Articles

- Guildford Institute’s Crowdfunding Project for Accessible Toilet in its New Community and Wellbeing Centre

- Letter: Guildford – Another Opportunity Missed?

- Letter: GBC’s Corporate Strategy – Where Is the Ambition?

- My Memories of John Mayall at a Ground-breaking Gig in Guildford Nearly Six Decades Ago

- Westborough HMO Plans ‘Losing the Heart of the Street’ Says Resident

- College Invests to Boost Surrey’s Economy and Close Digital Skills Gap

- Community Lottery Brings Big Wins for Local Charities

- GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Hospital Pillows ‘Shortage’ at the Royal Surrey

- Updated: Caravans Set Up Camp at Ash Manor School

Recent Comments

- Ian Macpherson on Updated: Main Guildford to Godalming Road Closed Until August 1

- Sara Tokunaga on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- Michael Courtnage on Daily Mail Online Reports Guildford Has Highest-paid Council Officer

- Alan Judge on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- John Perkins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

- S Collins on GBC Housing Plan Promises ‘A Vibrant Urban Neighbourhood’ Near Town Centre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Ruth Brothwell

September 4, 2020 at 3:47 pm

I believe this was the raid that dropped a bomb in Anderson Road, Oatlands Village which caused the front of my Grandparents Cottage to cave in. They were under the table at the time but the story remains part of family history.

John Hancock

September 6, 2020 at 11:38 am

As a lifelong aviation history enthusiast, I would like to add a contribution. I believe that I witnessed, 80 years ago(!), the beginning of the attack by the “top cover” of the Me110s that day.

Aged eight and standing in our garden in Western Hounslow one lunchtime, on a good Autumn day, I was riveted by the sight of a neat formation of 110s flying fast and westwards.

Right above me, they were attacked by Hurricanes and the port engine of one of the Messerschmitts began to trail smoke, the machine slowly falling out of formation. All this in a few seconds and gone.

The ‘top cover’ had swung east towards Weybridge, perhaps two minutes flying time from where I stood.

Dave Goodwin

September 10, 2020 at 8:50 am

Both my mother and father worked at Vickers during the war in the machine shop, both on night work. I also worked there in the 1960s and in places you could see damage to steel supports. One of my setters was there at the time of the raid but fortunately, he had gone home for lunch. Had he been at his place of work he would have been killed. Sadly I can not remember his name but it was clear he was very affected by the incident, so tragic.

My father was not allowed to join up as he was a key worker in engineering but he never talked much about the war I believe this was when they moved machines out to peoples garages and the like.

My parents were George and Mini Goodwin.

Ben Darnton

September 12, 2020 at 8:00 pm

My grandfather witnessed the raid but fortunately was late back to work so he dived under a car to take cover.

He made light of it but he must have seen some terrible sights as he was first on the scene.

Thorkild Joergensen

September 21, 2020 at 3:05 pm

Very interesting to read about.

I’m always looking out for news about Me110 since I’m working on a 110 (LN+DR) at Sola Air Museum (near Stavanger).

Susan Cadby (nee Owen)

June 7, 2021 at 11:34 am

Does anybody know if there was ever a list made of all those Vickers Armstrong workers who were injured in this bombing please?

I believe my grandad Reginald Frank Owen worked there around that time.

When I knew him, from 1947, he had a permanent straight leg causing him to limp and I am wondering if it was caused in this bombing.

Frank Phillipson

June 8, 2021 at 3:03 am

I do not believe that there is a surviving list of people injured in the raid. I have put together, from various sources, a list of those killed but have not come across any listing of the over 400 injured.