Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

County Council Director Addresses Failures That Contributed to Teen’s Suicide

Published on: 8 Dec, 2021

Updated on: 10 Dec, 2021

The Coroner’s Court, Woking where the “prevention of further deaths” hearing was held. Photo – Julie Armstrong

By Julie Armstrong

local democracy reporter

Surrey’s director for education said she has reflected deeply on the failures of the special educational needs department which a coroner said contributed to the death of an autistic 14-year-old.

Liz Mills, director of education, lifelong learning and culture at Surrey County Council, told a “prevention of further deaths” hearing at Surrey’s coroner’s court on Thursday (December 2) that Oskar Nash’s education health and care plan (EHCP) was inadequate.

Oskar died when he took his own life on a railway line in January 2020.

She said the council was now ensuring every new EHCP and annual review is seen by a panel that includes an educational psychologist, and is also sharing notes from a child’s last annual review with any prospective school.

Ms Mills told the court: “I’ve reflected very fully on the important learning that has come through this very tragic case.”

It follows a coroner’s conclusion in September that the department’s failure to ensure Oskar’s care plan contained sufficient and updated information about his mental and emotional health needs, as well as its failure to place him in a school appropriate to meet his complex needs, probably more than minimally contributed to his suicide on the railway line near Staines last year.

Senior coroner Richard Travers said in the hearing: “In my view, the placement of Oskar in Cobham Free School placed him in an environment which led to the crisis which emerged in November 2019.

“Given Oskar’s history at his earlier schools, this was entirely foreseeable, and proper review of the information which was readily available, would have made it clear that Oskar would not cope, and that the risk of suicidal ideation would consequently re-emerge.”

When Oskar was 10, the council refused a request made by his primary school to conduct an assessment into whether a statement, now called an EHCP, was needed to outline what extra support the school should provide.

By the time it came to an EHCP being issued in 2017, eight years after he was diagnosed, Oskar had a significant history of suicidal ideation and the family was at breaking point, the court heard.

When he did eventually get the plan, what went into it was not what his paediatrician Dr Francesca Tennant had raised.

His first secondary school, St Dominic’s in Godalming, offered much more specific provision. Had this gone into the plan, it would have made it a legal requirement for his next school to provide it.

Alison Hewitt, the coroner’s barrister, asked: “Is there a reluctance because of the impact on budget?”

Ms Mills replied: “No I wouldn’t agree with that. Our service is very much concerned with understanding need and meeting it.

“It’s currently spending in excess of its funding arrangements, so we’re not putting funding arrangements ahead of meeting the needs of children.”

She said guidance had been given to caseworkers that provision in the EHCP should be specific, and that was underpinned by recent training from IPSEA (Independent Provider of Special Education Advice).

Oskar wanted to move to a mainstream school and the SENCO (special educational needs coordinator) at St Dominic’s said he would first need to be assessed by an educational psychologist, but that did not happen.

After a visit to Oskar’s primary school, a member of Surrey council’s specialist teachers for inclusive practice team said he would not cope in mainstream schooling. Oskar did not accept his diagnosis of Asperger’s and was threatening to kill himself.

But this was not noted in the EHCP, and so when Oskar joined Cobham Free School they were oblivious.

The school indicated it could meet Oskar’s needs on the basis of his EHCP, which had been drafted nearly three years earlier and did not capture recent events, such as him cutting himself or fleeing from school requiring the police to be called.

Cobham was not given the two annual reviews conducted by St Dominic’s, which outlined specialist support not in the original plan.

Ms Mills said: “I acknowledge fully the plan we had was not at all adequate and we must reflect deeply on that.”

She said the EHCP was “the core vehicle with which to consult the schools” and should have all the relevant information required to make a decision.

If schools were also required to share all the school records, including safeguarding files, she said the volume of information would become “overwhelming” for schools and they would not have the capacity to review everything.

The SEN team had not attended Oskar’s annual review but: “That simply wouldn’t be practical because of the volume”.

Out of 160,000 school-age children in Surrey, 11,600 (7.25 per cent) have an EHCP.

Each caseworker is dealing with about 150 EHCPs, which Ms Mills said was not a lot compared to neighbouring authorities.

She outlined what had been done since Oskar’s death:

- A Learners’ Single Point of Access (L-SPA) was introduced in July 2020 to advise parents and schools on how to access a range of support without the need for a statutory assessment, with the aim of intervening earlier.

- Every new EHCP and annual review is seen by a panel that includes an educational psychologist. The four panels look at each other’s work as well as being overseen by assistant directors.

- In 2019 the council invested in “independent but experienced” SEN workers to do dip sampling. In 2020 it employed a second clinical worker to give medical advice.

- From April 2021 the council has piloted tools enabling parents to audit EHCPs against expected standards, which it has now decided to adopt.

- Ms Mills said there are “no national set standards for a SEND caseworker role” but the council has adopted two “very well recognised professional qualifications” – IPSEA (Independent Provider of Special Education Advice) and NASEN (National Association for Special Educational Needs).” She said this mandatory training started in 2020.

- Eighty school leaders out of 400 schools had also put themselves forward in the last academic year for training in SEN, which presents as autism in a third of cases.

Oskar had been diagnosed with autism at the age of four. When he was eight his mum referred him to children’s services but his primary school Riverbridge said he had “autistic traits but he didn’t need help; if he did he would be statemented”, the court heard.

Oskar was intelligent and felt labelled “dumb”, and would ask his mum why he was not given homework like other pupils.

Ms Hewitt asked the director for education: “Why is there not a system in place for the diagnosis to result in some formal assessment of what SEN if any follows from that condition?”

Not every child with autism has special educational needs, Ms Mills said in her witness statement. In court she agreed autism was “very likely to have some impact on a child’s learning” and the likelihood of having to make some changes was “quite high”.

She also recognised the high prevalence of self-harm and suicide among people with autism.

Ms Mills said currently over 2,000 applications were made for EHCP assessments each year and four in five of these were accepted.

“The system as it is set out firstly relies on a parent notifying the school if a child has identified need,” she said.

She said the local authority only has to be notified of a child’s SEN when they are under compulsory school age, and once a child reaches school age the responsibility was “firmly fixed with the schools”.

Asked how this was monitored, Ms Mills said by Ofsted inspections, and every school is required to have a qualified SENCO (Special Educational Needs Coordinator.

The hearing continues.

Samaritans can be called for help 24/7 on 116 123.

Click on cartoon for Dragon story: Public Asked for Views on SCC’s Proposal for Reduced Speed Limits

Recent Articles

- Letter: We Should All Have a Say in How Our Local Government Is Reorganised

- Dragon Review: Madam Butterfly – Grange Park Opera

- Letter: PIP Claimants Under-claim

- Flashback: Council Report Accepts Juneja Case Has Caused ‘Reputational Damage’

- Revealed Survey Shows SCC’s Preferred Two-unitary Option Has Least Public Support

- Highways Bulletin: Junction 10 Closures and Making Strides for Walk to School Week

- New River Boats for Surrey Care Trust

- Body Found in Woodland Believed To Be Missing 69-year-old

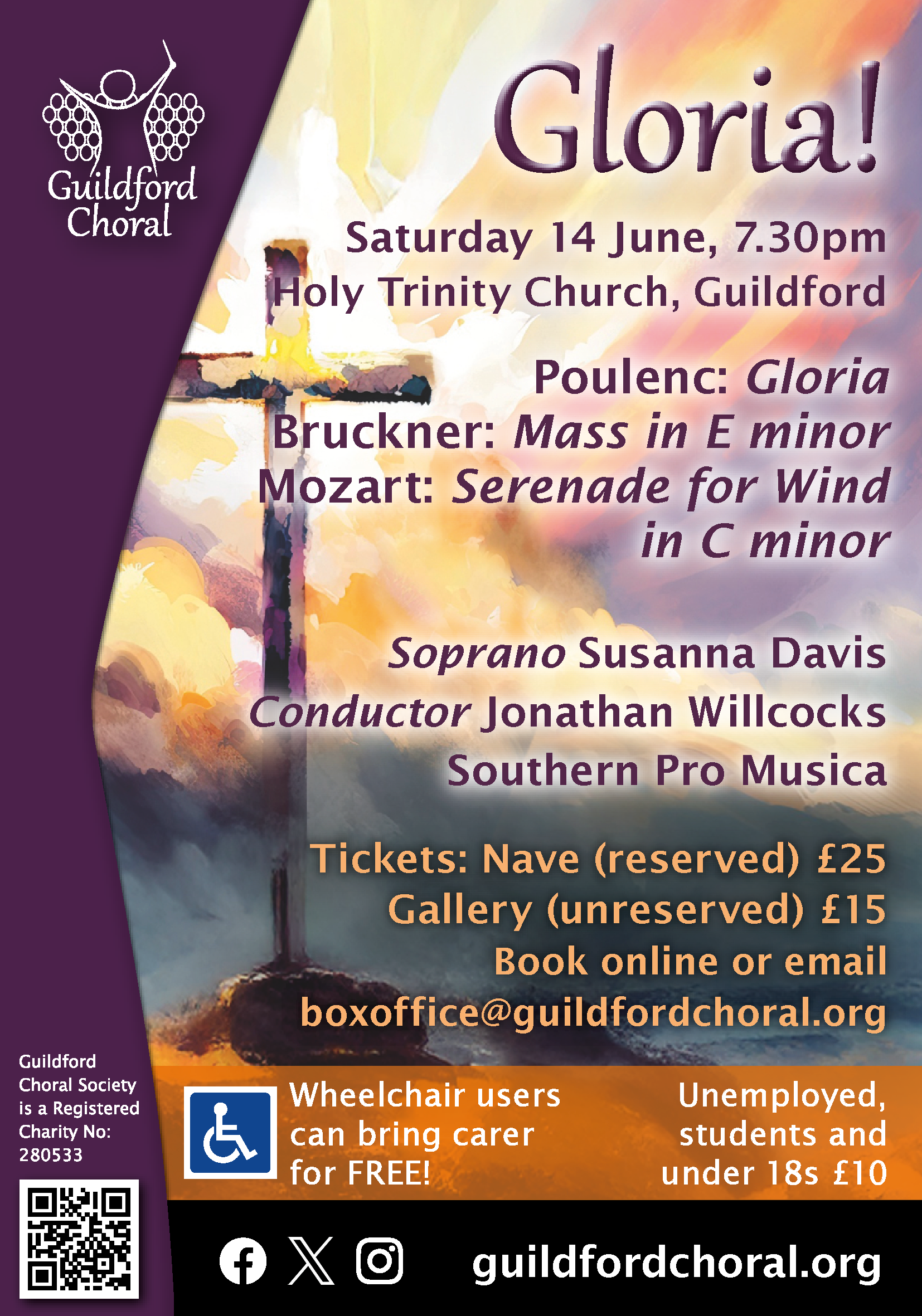

- Guildford Choral Promises a Summer Evening Spectacular

- Volunteers Are Needed To Test My Wearable Wellbeing Technology

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments