Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley and His Grand Funeral in London and Pirbright

Published on: 21 Apr, 2025

Updated on: 21 Apr, 2025

By Mark Coxhead with David Rose

The great explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician, Sir Henry Morton Stanley, is buried in the churchyard of St Michael’s and All Angels, Pirbright.

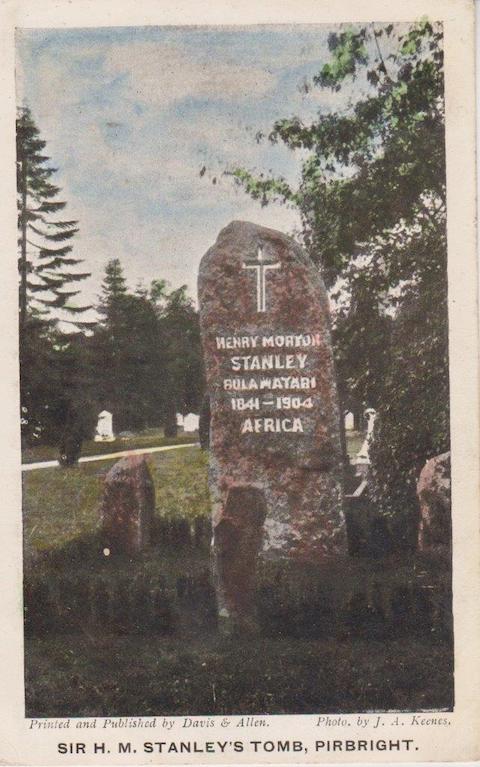

Early 1900s picture postcard of the grave of Sir Henry Morton Stanley in Pirbright churchyard. Mark Coxhead collection.

The headstone above his grave is both huge and imposing – a lump of granite inscribed with the words: “Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841-1904, Africa.”

Bula Matari can be translated from the Kikongo language to mean “breaker of rocks”.

This was a name given to him by Africans in the Congo when he spent time there working alongside labourers as they broke rocks while building the first modern road along the Congo River.

He is perhaps best remembered for speaking the words: “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”

This was when Stanley was one of the New York Herald’s oversees correspondents. At the time the Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone was in Africa, but whose whereabouts were unknown.

The explorer Henry Morton Stanley. Picture: Wikimedia Commons.

Stanley led an expedition to find Dr Livingstone and eventually found him on November 10, 1871 in Ujiji near Lake Tanganyika in present-day Tanzania.

There appears to be no truth Stanley actually spoke those words when he greeted Dr Livingstone. Those words may have been made up by a writer as a bit of journalistic licence as the news of the meeting between Stanley and Dr Livingstone went around the world.

In his later life, as Sir Henry Morton Stanley, he and his wife Dorothy had a “country retreat” named Furze Hill, on the outskirts of Pirbright.

He died on May 10, 1904 at his London home.

The Woking News & Mail reported his death in its edition of May 13, noting he had died at 6am, at his residence on Richmond Terrace, Whitehall, adding: “Sir Henry remained conscious until his final moments, and although he was unable to speak, he recognised his wife and sister-in-law, who, alongside his male nurses, stayed by his side through the night.”

The following week’s Woking News & Mail reported on Sir Henry’s funeral, that was grand to say the least.

It noted the first part of the service was held at midday at Westminster Abbey. The Dean officiated and “a distinguished congregation gathered to pay their last respects to the renowned explorer”.

Adding further details that Lady Stanley, accompanied by her young son Denzil Stanley, led the procession along with family members and close friends.

The coffin, made of English oak bore the inscription “Henry Morton Stanley, G.C.B., D.C.L., LL.D., Ph.D., ‘Bula Matari,’ Explorer of Africa.”

The service began with the choir performing Purcell’s funeral music, with the report noting: “The melodies resonated through the Abbey, complemented by sunlight streaming through the stained-glass windows. As the procession moved past the grave of David Livingstone, the two great explorers symbolically met once again—not in the Congo but in death and their nation’s place of honour.”

The coffin was then carried to the “waiting funeral car, drawn by four horses and the procession left the Abbey for the Necropolis Station”.

Sir Henry’s body was conveyed by train from the London Necropolis & National Mausoleum Company’s station, whose entrance was on Westminster Bridge Road, not far from Waterloo station, to Brookwood station.

The newspaper’s funeral report continued stating that in the afternoon Sir Henry’s remains were interred at Pirbright, with the report adding where “Lady Stanley regularly worshipped and Sir Henry occasionally joined”.

Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s body was conveyed by a train like this by the London Necropolis & National Mausoleum Company London, to Brookwood station.

A “special train” carried mourners to Brookwood station, “before transferring the coffin to a glass carriage for the remainder of the journey to the cemetery [sic].

The Revd A. Krauss, led the graveside service, reading the committal sentences “with solemnity”, with the report pointing out: “The ceremony was simple yet moving, contrasting with the grandeur of the Westminster Abbey service.”

Late 19th century photograph of St Michael’s and All Angels Church, Pirbright. Picture: the late Patsy Burch (nee Rice).

Also mentioned was that: “Local residents and parishioners gathered to pay their respects, with houses closed and shops shut as a mark of honour. Among those present at the graveside were Lady Stanley, local dignitaries, and employees of Furze Hill, Sir Henry’s residence.

‘The coffin was placed in a modest grave located in a picturesque corner at the eastern edge of the churchyard. A large crowd gathered, lingering briefly to pay their respects and catch a glimpse of the coffin before quietly dispersing. Among those present at the graveside were Mr Muirhead, the steward, and employees of Furze Hill, including Messrs Rose, Hill, Sayers, and Lough.

“Local residents, such as Mr Ross Mangles, VC; Mrs. T. Mangles; Major and Mrs Armstrong; Dr Russell; and other notable figures, also attended to honour the deceased.”

Lady Pirbright placed a wreath on her husband’s grave, and the newspaper report even added: “The police presence, directed by Deputy Chief Constable Page, was managed with assistance from Inspector Upfold and Sergeant Marshall.”

The huge granite headstone with additional stones marking the grave seems to have been placed in the months following his death, as a story in The Times newspaper in October that year reported: “We have received from the Art Memorial Company, of West Norwood, some striking photographs of the monument erected on the grave of Sir Henry Stanley in Pirbright Churchyard.

“A large block of un-hewn stone, shaped roughly like a column, which was found lying horizontally on Dartmoor, has been erected at the head of the grave. Facing it at the foot, and at the four corners, are smaller blocks of the same stone joined by a simple border of yew.”

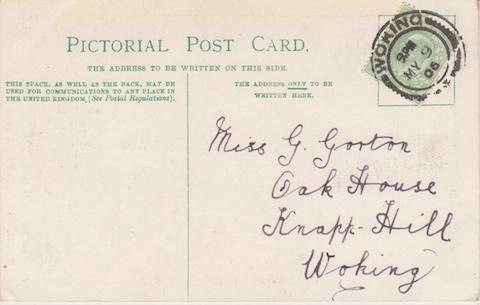

A portrait-shape picture postcard view of the grave of Sir Henry Morton Stanley in Pirbright churchyard. Mark Coxhead collection.

The reverse of the above postcard, sent to Miss G. Gorton, Oak Hill, Knap Hill, Woking. Although the sender of the postcard did not write a message, the postmark (or cancellation) is May 9, 06. That was two years minus a day after the death of Sir Henry Morton Stanley. Mark Coxhead collection.

By the early 1900s, the picture postcard craze was sweeping through Britain with topographical views of every hamlet, village, town and city the length and breath of Britain being photographed and published as picture postcards.

Villages in Surrey including Pirbright were liberally photographed and issued as postcards including Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s grave, as several examples are known and are featured here.

Yet another picture postcard view of Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s grave, this one published by Francis Frith & Co of Reigate. David Rose collection.

The grave looks much the same today (2025) with its headstone, granite stones surrounding it and clipped yew bushes.

Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s grave as it looks today (2025). Also buried there is his wife, Dorothy, who died on October 5, 1926. Also commemorated are Denzil Morton Stanley 1895-1959, Helen Liddell Stanley 1891-1979, and Richard Morton Stanley 1934-1986.

Stanley was born John Rowlands in Wales in 1841 of unmarried parents. He had a harsh upbringing, spending 10 years as an inmate in a workhouse. However, when he was 18 he began a new life in the USA.

He was befriended and then adopted by Henry Hope Stanley, a wealthy trader. John Rowlands eventually changed his first name to Henry and his surname to Stanley.

Among the many adventures he had during his life, it was during the American Civil War that he first fought for the Confederate army, then defecting to the Union. He even had a spell with the US Navy, before he deserted.

He then became a journalist. Following his expedition to find Dr Livingstone, he returned to Africa in 1874 tracing the course of the Congo to the sea.

In 1876, the Belgian King Leopold II, whose intention was to introduce Western civilisation to the Congo, hired Stanley to negotiate with tribal chiefs to obtain fair concessions. Unbeknown to Stanley, King Leopold II wanted to claim the lands for himself.

Stanley refused to impose treaties on the tribal chiefs that would, of course, result in them losing their lands.

In 1886, Stanley led the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition to “rescue” Emin Pasha, the governor of Equatoria in the southern Sudan, who was threatened by Mahdist forces.

Stanley eventually returned to England and became a Liberal Unionist MP, serving Lambeth North from 1895 to 1900.

He was knighted in 1899 for his services to the British Empire in Africa.

There is more to read about Sir Henry Morton Stanley on his entry in Wikipedia.

His legacy does include a number of controversies about him including indiscriminate cruelty against Africans.

Part of his page on Wikipedia includes: The British House of Commons appointed a committee to investigate missionary reports of Stanley’s mistreatment of native populations in 1871, which was likely secured by Horace Waller, a member on the committee of the Anti-slavery Society and fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. The British vice consul in Zanzibar, John Kirk (Waller’s brother-in-law) conducted the investigation. Stanley was charged with excessive violence, wanton destruction, the selling of labourers into slavery, the sexual exploitation of native women and the plundering of villages for ivory and canoes. Kirk’s report to the British Foreign Office was never published.”

Recent Articles

- Letter: Stoke Mill Needs Protection

- Letter: Why Is No One Applying to Waverley Council’s CIL Review Scheme?

- Highways Bulletin: Supporting You Through Local Roadworks

- Warning Over Rising Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Guildford

- Letter: The Lack of Political Will to Fix the CIL Issue at Waverley Is Worrying

- Notice: Heritage for All

- Letter – Waverley Council’s Answers on CIL Just Don’t Make Sense

- Cyclist Seriously Injured in East Clandon Collision – Police Seek Witnesses

- GBC Admits ‘Significant Failings’ Over Couple’s Home Improvement Ordeal

- Community Governance Review Explainer

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments