Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

“Life Sentence”: A Short Story About How Age Can Steal Our Liberty But Strengthen Love

Published on: 10 Aug, 2024

Updated on: 10 Aug, 2024

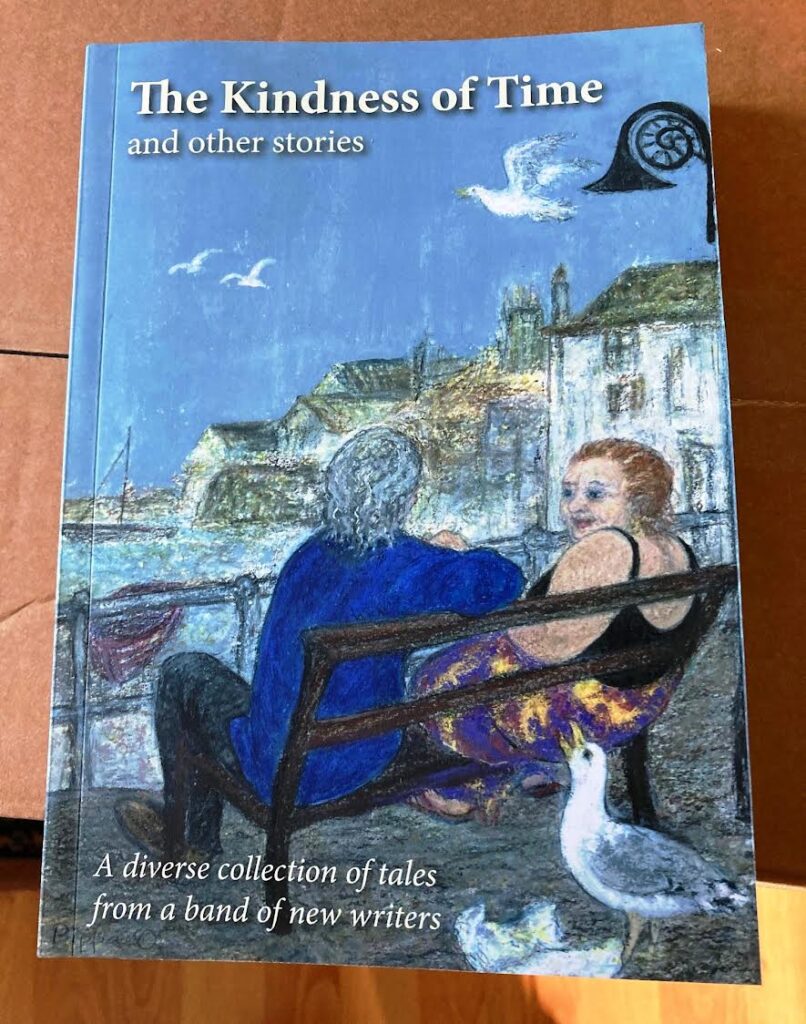

During lockdown, Guildford Dragon reporter David Reading teamed up with two friends, both ex Guildfordians, to write and self-publish a book of short stories. The profits are going to local children’s charity Challengers. The following story is part of the collection.

During lockdown, Guildford Dragon reporter David Reading teamed up with two friends, both ex Guildfordians, to write and self-publish a book of short stories. The profits are going to local children’s charity Challengers. The following story is part of the collection.

Life Sentence

By Alexis Krite

Today is Friday, the day Angela comes to visit. I don’t know why she comes to see me. I don’t think she likes me. Perhaps she thinks she loves me. Perhaps she’s worried about regret. It could be guilt. It could be the fine traces of Catholic duty that nestle in the ley lines of her body. Perhaps she sees herself in me, sitting here, in a care home just like this, in thirty years’ time.

To be honest, I have no idea. But Friday is the best day of the week for me.

There’s a knock on the door. There’s no need to knock, the door is open. It’s just a throw-away gesture to me. As if I have a say in who comes in, and who doesn’t.

“Hi Mum.” She sets her shopping bag down on the bed and walks over to me. Just three steps is all it takes. The room is so small. She leans down and brushes my cheek, the barest touch of her lips. She smells of cold air and peppermint.

“You’re looking well,” she lies. “Gosh it’s warm in here.” She pulls her coat off and folds it neatly on the bed, next to her shopping bag.

“Hello darling,” I greet her. “How was the journey?”

“Oh, you know, usual mad traffic. I didn’t get away till late, so I got caught in the rush.”

I nod, letting her see that I appreciate she has put herself out for me.

“You could have just called, saved yourself that drive.” I give her permission to elaborate on the effort she has made.

“It’s not the same. Besides, I’ve got you a few bits and pieces.” She opens the shopping bag and takes out a pack of face wipes, a bar of Yardley Rose soap, a packet of chocolate-covered crystallised ginger and a tin of white crab meat.

“Ooh lovely! I’ll have that for my tea.” I actually do like white crab meat. Sometimes she brings me smoked salmon: slivers of pink that sit like diaphanous shreds of fabric on my plate. I’ve seen the other residents look enviously at them. I know for a fact that Elsie, the one that discovers my room every hour or so, has slipped a piece into her hanky at least twice. But I don’t begrudge her. She glances mischievously around her before lifting her hand, quick as a flash, to my plate. Sometimes I pretend to look the other way. At other times I turn my back on her so I can eat all the salmon, letting it melt on my tongue and then, one or two chews, and down it slithers. Delicious.

Angela sits on the bed. She doesn’t like to use the only other chair in the room. She knows what lies hidden beneath the plastic-covered foam cushion. I tell her I don’t often use it; that I still get plenty of warning when I have to go. All I need to do is ring the bell and the soft-eyed little Filipino nurse helps me gently and respectfully to the bathroom. She never compromises my dignity. I am grateful for that.

“Shall I put the telly on?” Angela picks up the remote control and switches on the BBC Celebrity Antiques Road Show. I watch her face as the images flicker on the screen.

Perhaps I should have told her the truth. Made a full confession. There is still time of course. But what good would it do? Would it make her happier? I don’t think so. She manages her life very efficiently. She’s good at her job, is respected by her colleagues and I’m sure she gets satisfaction from helping people find homes. People who have been on the streets for years. She does more good than I ever did.

But I don’t think she has ever forgiven me.

When her father fell from that balcony and broke his neck on the crowded, heat-cracked street in Athens, no-one blamed me. The police said he had been drinking. They were sympathetic, everyone was very kind. Would they have been so kind if they had known that I had actually stepped aside and let him fall?

He had lunged at me, his breath stinking of whisky, fist knotted into a ball, ready to crack my jaw again. I could have reached out and blocked his way. He might have crumpled then, onto the marble tiles. But I stepped aside and gripped the balcony door. The weight of his anger and a gentle push from me carried him on. It carried him on towards the balcony rails, on and over into oblivion. And I became a murderer and a widow with a grieving daughter who had adored her father.

It was a long time coming. This life sentence. But finally, here I am in this room that is my prison cell. With no hope of parole.

When it happened, Angela was at boarding school. I told her it was an accident. Everyone told her the same. But I saw the way she looked at me and I realised she knew. She knew because of the bruises I hid with foundation and the way I would wear long-sleeved dresses even in summer. She was always a daddy’s girl. I had never taken to her. The moment she was born I looked at her little face, scrunched up and primate-like, and I felt like something had been removed from me.

I tried to love her. I dressed her in pretty clothes, bought her Sindy dolls and paid for riding lessons. But it was always the same. Each time I closed my eyes against her cheek to inhale her warm child’s breath, I could feel his face pressed into mine, pinning my mouth down with his. In the dark, as I lay with her in my arms, I remembered how he had ripped into me; how he had discharged his fury and his despotism, marking me forever as his.

My parents decided we should marry. It was the right thing to do, and quickly. My mother rarely spoke to me after the wedding, my father left the room each time I entered. But their friends and neighbours were delighted for them. I had made such a good marriage.

And now, here Angela sits. She will glance at her phone from time to time and at 18.50 exactly she will say her goodbyes and leave.

“Angela,” I say. She looks at me and smiles. “Yes?”

“I’m sorry I made you do it. I wish I’d done things differently back then.”

She looks away. “You did what you thought was best.” She is being generous with her ninety-year-old mother, generous to the woman who forced her to have an abortion.

“Darling, it’s just that…”

“Yes, I know Mum. You didn’t want me to make the same mistake.”

I try to protest. “It wasn’t a mistake, you weren’t a mistake.”

Sometimes I think I was acting out of vindictiveness. Jack would never have done to her what Richard did to me. Jack was kind, not very bright, and very young.

She stands up and looks out of the window.

“I don’t suppose I would have been a very good mother anyway, but…” And she turns to me. “I never had the chance to find out.”

There are tears in her eyes. Something stirs inside me. I can’t identify it. I think it might be love.

Angela stuffs her shopping bag into her pocket and picks up her car keys. She bends and very lightly kisses the top of my head. “Salmon next week?”

“Yes please, darling, that would be lovely.”

She walks through the door. I call after her. “And a crusty roll!”

I hear her laugh.

The short story collection, “The Kindness of Time and other Stories,” costs £9.95, plus £3.60 postage and packing per book. Profits are going to Challengers.

The short story collection, “The Kindness of Time and other Stories,” costs £9.95, plus £3.60 postage and packing per book. Profits are going to Challengers.

To order a copy please email karinewbery1@gmail.com with Book Order in the subject line.

Please include the number of books you would like, your full name, delivery address and preferred payment method: BACS or Paypal.

To avoid postage and packing costs, delivery could be arranged to people in the Guildford area. Email david.reading@live.co.uk.

Recent Articles

- Letter: Stoke Mill Needs Protection

- Letter: Why Is No One Applying to Waverley Council’s CIL Review Scheme?

- Highways Bulletin: Supporting You Through Local Roadworks

- Warning Over Rising Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Guildford

- Letter: The Lack of Political Will to Fix the CIL Issue at Waverley Is Worrying

- Notice: Heritage for All

- Letter – Waverley Council’s Answers on CIL Just Don’t Make Sense

- Cyclist Seriously Injured in East Clandon Collision – Police Seek Witnesses

- GBC Admits ‘Significant Failings’ Over Couple’s Home Improvement Ordeal

- Community Governance Review Explainer

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments