Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

New Feature Series: Guildford Cathedral’s Fascinating Hidden Spaces Are Revealed

Published on: 13 Apr, 2019

Updated on: 13 Apr, 2019

The cathedral angel in the clouds but striving to stay relevant in the modern age, supporting the mobile ‘phone mast.

by Hugh Coakley

Loved or loathed, Guildford’s Cathedral Church of the Holy Spirit is a monumental building, both inside and out, which we who live in Guildford would miss hugely were it not there.

But our cathedral has a dilemma.

Despite its wonderful professional choir it has low attendances at services, struggles financially and is in an isolated position out of town. It is better known to Guildfordians as a landmark and a setting for the film The Omen than as a place of worship or a community asset.

So how does the cathedral marry its mission of being a “place of prayer, reflection, work and celebration” to the difficult position it is in?

The Guildford Dragon NEWS will be running a series of feature articles on Guildford Cathedral, examining the building, touching on the community who serve there, the monastic pulse that fills the light and glorious space, the daily and weekly events in the historic building and the 21st century challenges the church faces.

In this first article, we will take a fresh look at the building itself. We invited the current cathedral architect John Bailey, a partner in the architectural firm, Thomas Ford, who specialise in maintaining and conserving religious buildings, to talk about it all and to show us the hidden spaces not usually seen by the public.

John said: “It is a privilege to work on this building. People do feel very strongly about it but I am deeply fond of it. It stands here as witness to a secular world.”

And for a building that looks so simple, there is so much immediate detail to take in.

Manhole in the floor to the service tunnel under the nave. The repeated decoration on the brass manhole are the three tongues of fire which are symbols of the Holy Spirit. The cathedral is called the Cathedral Church of the Holy Spirit. Click on the image to enlarge it and see the detail.

Just inside the west end at the main entrance, there is decorated brass disc set into the floor. You wouldn’t think it but it is actually just a manhole leading to the service tunnel which runs under the aisle, nearly the full length of the church.

The disc typifies the whole building; simple, elegant, understated and very beautiful.

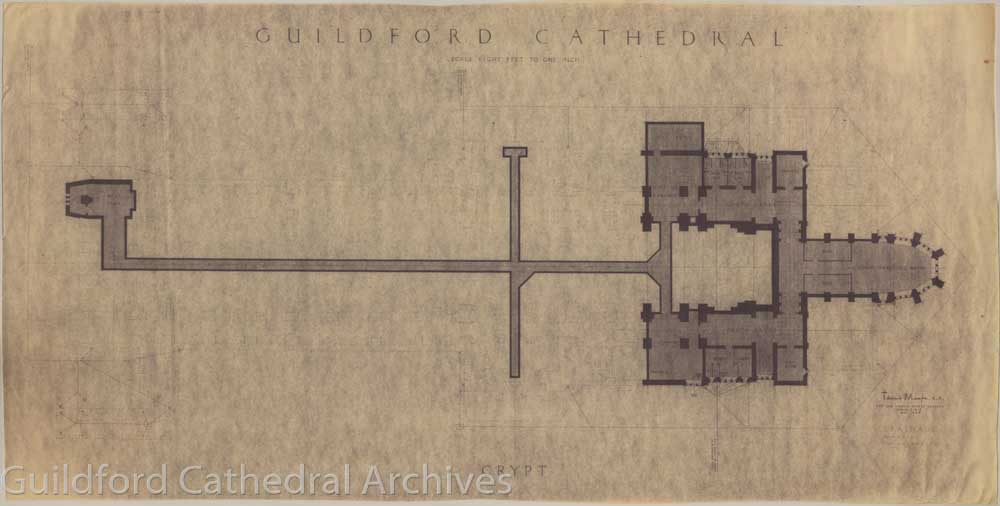

About 20% of the plan area under the cathedral is crypt or tunnel and still used in the operation of the building. This includes the crypt below the Lady Chapel at the eastern end which was the main chapel for services between 1947 and 1961 before the cathedral was consecrated and open.

Plan of Guildford Cathedral’s crypt and service tunnel. The tunnel runs the full length of the aisle and the crossing. Click on the images to enlarge them in a new window.

We went into the crypt, not via the manhole but by a set of concrete steps past the Treasury. The crypt is dry and functional, as you would expect from a reinforced concrete structure. But it does have its glamour.

At the end of the cross passage tunnel, John pointed out the original cathedral strongroom. Local historian David Rose said some people say that the Guildhall clock and other civic artefacts were stored at the cathedral during the Second World War. The cathedral’s strongroom would have been appropriate, said John, with its concrete walls and roof to protect it from enemy bombs.

Door to the original strongroom in the cross passage crypt tunnel, rumoured to have stored the town clock during the war.

The tunnel itself holds a maze of pipework for the underfloor heating and the roof seemed to get lower towards the west end. Squeezing under the roof and the pipes was definitely not for the claustrophobic.

The tunnel under the central aisle looking towards the west end. Very restricted – not for those who dislike confined spaces.

It’s very cosy down there with the separate choir rooms, one each for the boys and girls choir and for the six lay clerks, which is what the professional adult, male singers are called.

Cosy, possibly, is not the right word, but parts of the crypt do have a lived-in, school feel about them.

From the crypt and up to the roof meant climbing a round concrete staircase and into various side passages. The fact that this is a modern concrete and brick structure, compared to older, stonework cathedrals, becomes very obvious in these passages.

But this is a special building and there has been a touching amount of care invested in the construction. The passages are arched instead of a simpler flat roof even though they are hardly ever seen by cathedral worshippers or visitors. But it has a lot of charm now.

Delightful concrete workmanship in the passages and the stairway to the tower, not a great finish but imaginative and full of gothic potential.

Higher and higher, I didn’t count the steps but I have no doubt someone has, to the concrete roof vaults under the copper-covered roof.

Architect John Bailey standing on the arch of the roof vaults under the roof itself. To his right is the access to the space under the roof, along the full length of the nave.

The roof vaults, the curved arches you see when you look up in the cathedral, are reinforced concrete. The roof itself is held up by a three-foot-thick solid brick construction, the very visible aspect of the cathedral that people often don’t like.

View through the space between the arched roof vaults and the roof itself. It seems to go on forever.

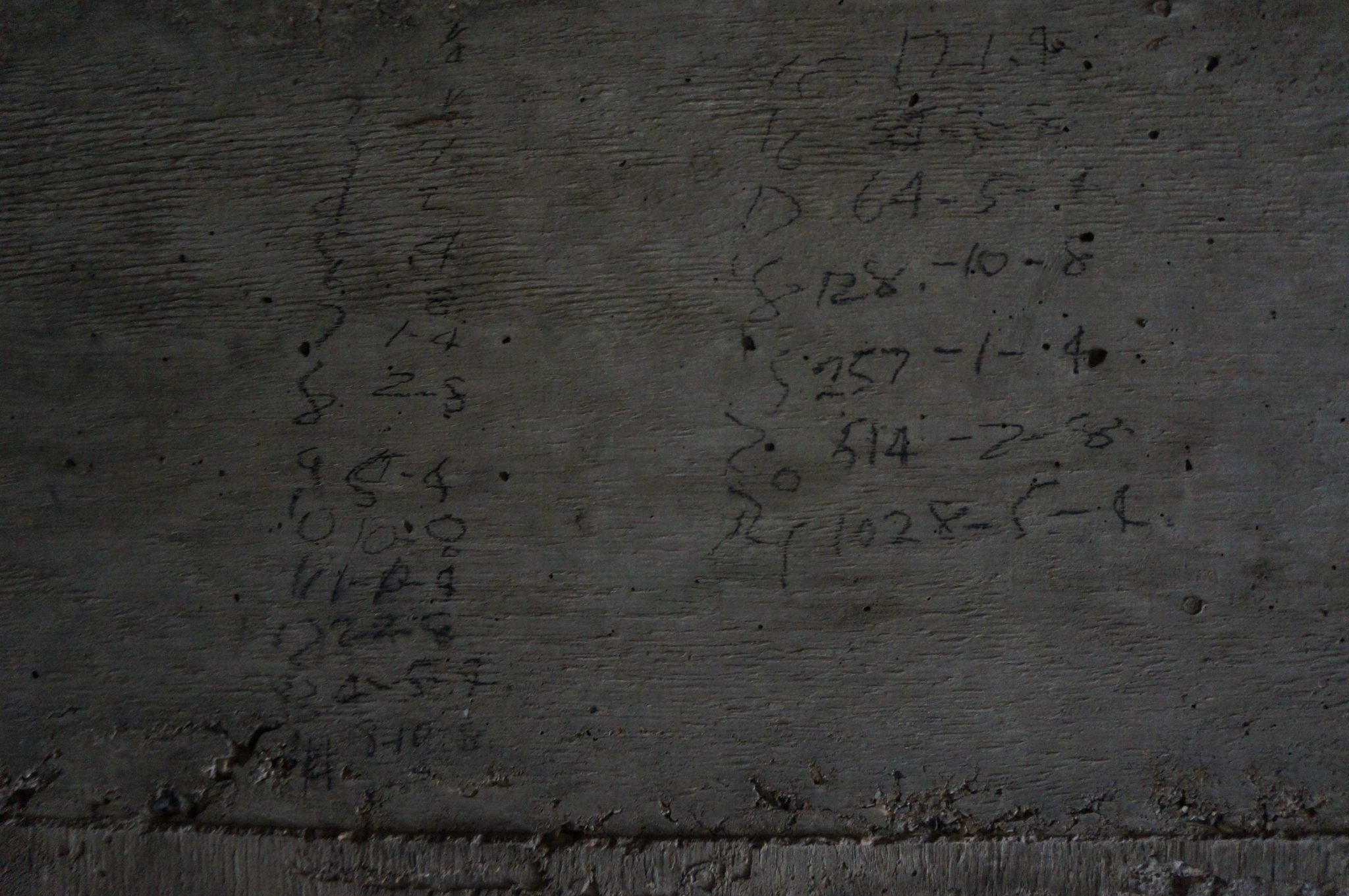

Workman’s jottings on the wall. Not clear when they were made or what they mean but they give a nice link to the men who worked on the construction of the cathedral over 80 years ago.

We passed through the room where the bell ringers to do their magic on the ropes, a large space, big enough to hold a dance. Then on upwards to the belfry itself.

Where the bell ringers work the bells. The bell ropes are arranged above and lowered when needed. The octagonal shape in the centre is the cover to an opening down to the cathedral floor 70 foot below. The opening is used when the bells need to be hoisted.

Looking up at the octagonal opening in the tower, underneath the belfry. The symmetry and simplicity are stunning.

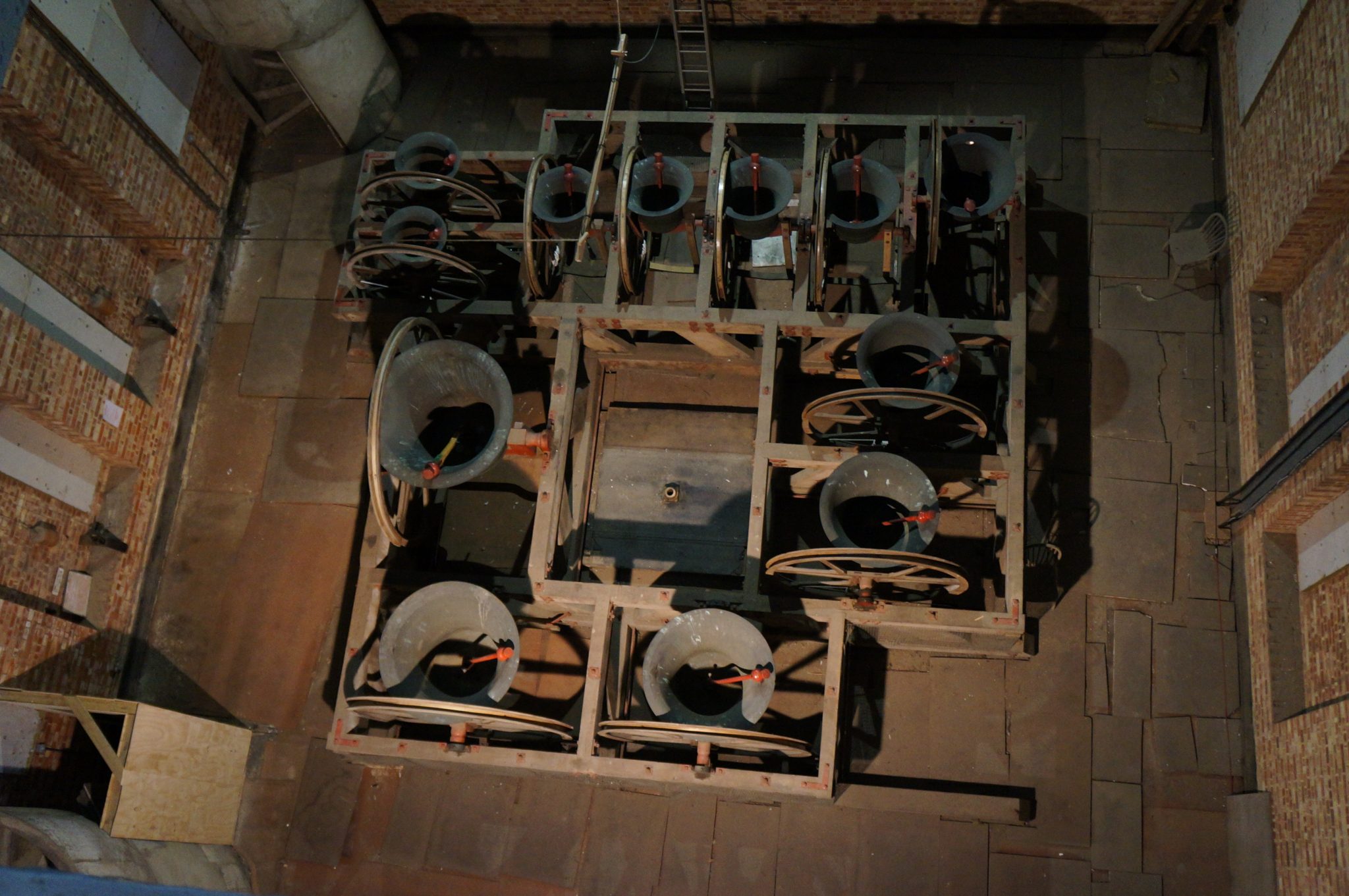

Looking down on the cathedral bells from the top of the tower. There are 12 bells with the largest weighing in at 1.5 tonnes.

And then, the angel himself.

He is not hidden, but you can’t visit the cathedral without acknowledging the landmark seen from all over Guildford. The angel was given in memory of Sgt Reginald Adgey-Edgar who died on active service in 1944 during the Second World War and erected in 1963. The supporting pole for the angel houses mobile phone antennas.

Looking north towards Woking where the 34-storey Victoria Square towers are being built. Some have dubbed them ‘The Towers of Mordor’. Click to enlarge the photo.

Looking around the building with architect John Bailey, there is a huge amount of detail which is hidden in plain view. From a distance, the building looks to be featureless. But that is not the case when you get close up.

Unaccustomed view of the cathedral from the east end, including the bell tower over the Lady Chapel.

A carved gargoyle projects out from some beautifully constructed brickwork, hardly visible from the ground.

And a couple of details from the inside as well. The original design and build architect Sir Edward Maufe’s contract stipulated that nothing was to be put in the cathedral, statue or artwork, without his expressed permission. He even had unfinished stone blocks in place, which could be carved later, to pre-empt any out of place decoration spoiling his design.

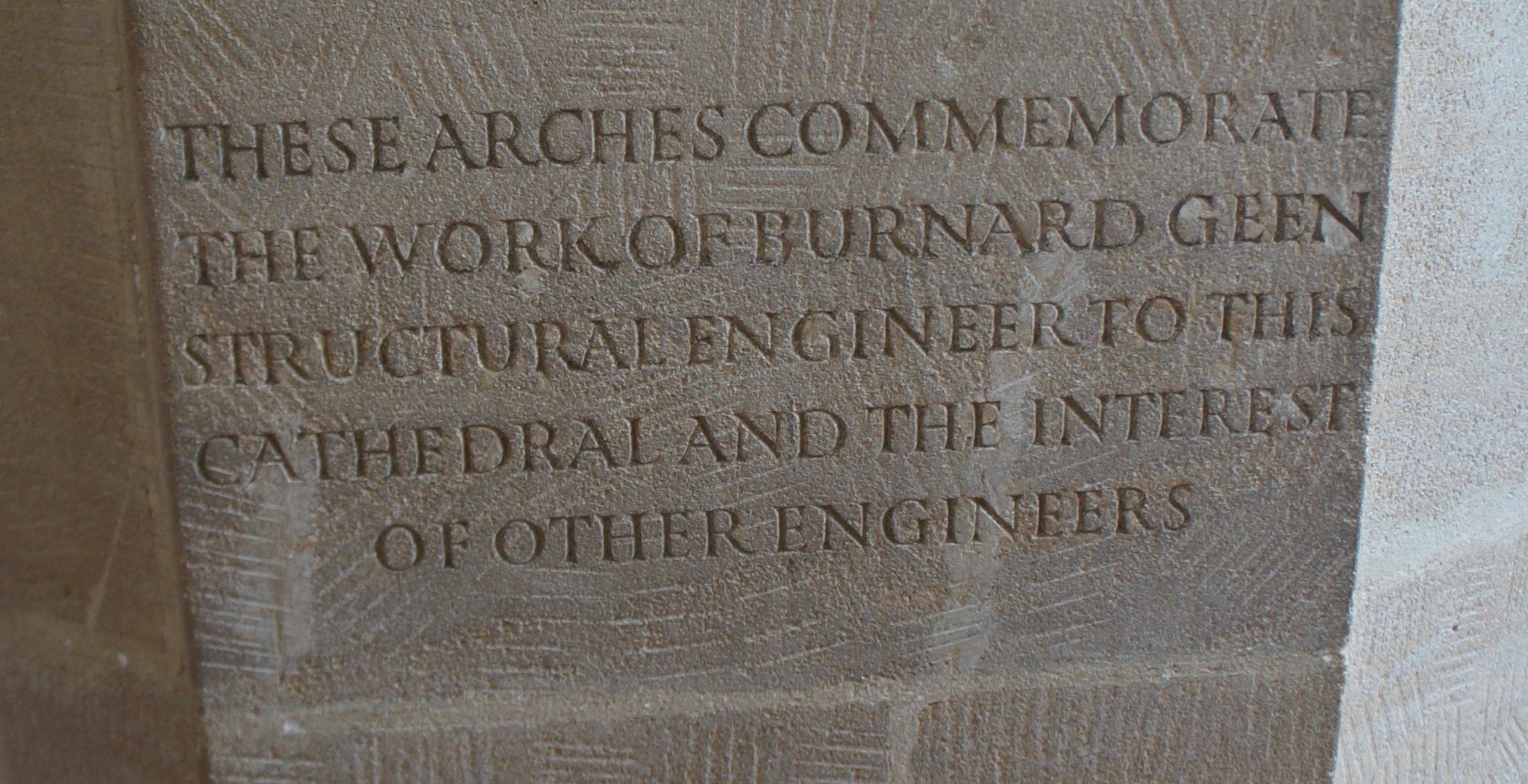

One of the limited number of memorials in the cathedral. It celebrates the engineer who designed the structure of this remarkable building. Note the irregular tool marks on the stone which is thought to be due to a lack of quality control in the later phases of the project.

John Bailey said: “Guildford Cathedral is never going to be in the Top 10 but it is a good building for Surrey. There is no reason why it couldn’t be here for a thousand years.”

Indeed, why not?

Next month: A Week in the Life of the Cathedral

Responses to New Feature Series: Guildford Cathedral’s Fascinating Hidden Spaces Are Revealed

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.Recent Articles

- Pedestrian Seriously Injured On Farnham Bypass – Police Appeal For Witnesses

- New Housing Planned To Replace Stables On Edge Of Wood Street Village

- Debt Charity’s New Report on State of Poverty in the South East and Help Available for People

- Local Government Reorganisation ‘A Great Opportunity To Start from Scratch’

- Notice: Poetry Competition – Enter by November 8

- Community Survey Planned To Discuss Future of the Troubled Electric Theatre

- 2025 Services of Remembrance to Honour our War Dead

- No Promise of A Mayor for Surrey

- Letter: This Decision Is an Outrageous Stitch-up

- The Spooky Hotel That Inspired The Winning Entry In Our Short Story Competition

Recent Comments

- RWL Davies on No Promise of A Mayor for Surrey

- John S Green on ‘Disaster in the Making’: Residents React with Anger and Distrust

- Amari Hawthorne-Bailey on Memories Of Queen Elizabeth Barracks And The Women’s Royal Army Corps

- Patrick Bray on It’s Two Unitaries for Surrey – SoS Says It Is Best Option for Financial Sustainability

- Mary English on Electric Theatre In Crisis As Financial Pressures Hit – Annual Loss of Over £250k

- Jackie Montague on Dragon Review: 2:22 A Ghost Story – Yvonne Arnaud Theatre

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Cllr Townsend on Waverley’s CIL Issue

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on Cllr Townsend on Waverley’s CIL Issue / Read MoreMP Zöe Franklin Reviews Topical Issues

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on MP Zöe Franklin Reviews Topical Issues / Read MoreMP Hopes Thames Water Fine Will Be ‘Final Nail in Its Coffin’

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on MP Hopes Thames Water Fine Will Be ‘Final Nail in Its Coffin’ / Read MoreNew Guildford Mayor Howard Smith

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on New Guildford Mayor Howard Smith / Read MoreA New Scene for a Guildford Street

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on A New Scene for a Guildford Street / Read MoreDragon Interview: Sir Jeremy Hunt MP on His Knighthood and Some Local Issues

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on Dragon Interview: Sir Jeremy Hunt MP on His Knighthood and Some Local Issues / Read MoreDragon Interview: Paul Follows Admits He Should Not Have Used the Word ‘Skewed’

August 27, 2025 / Comments Off on Dragon Interview: Paul Follows Admits He Should Not Have Used the Word ‘Skewed’ / Read MoreDragon Interview: Will Forster MP On His Recent Visit to Ukraine

August 27, 2025 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Fiona Davidson on the ‘Devolution’ Proposals for Surrey

August 27, 2025 / No Comment / Read More

Stuart Barnes

April 14, 2019 at 2:54 pm

I am amazed at the introduction to this interesting article. Surely no one could loathe the Cathedral? It is certainly not a thing of beauty but it is not something to be loathed. It should be supported.

Valerie Thompson

April 16, 2019 at 3:44 pm

One of the problems facing Guildford Cathedral is the refusal, by several local choirs, to plan their concerts there any more.

After the asbestos-containing plaster was removed and modern plaster replaced it, the acoustic – never brilliant in the first place, became quite impossible to tolerate. The cathedral, therefore, is losing a great amount of much-needed revenue as a consequence.

Many suggestions for improvements have been made, including my own, proposed in a letter to the Dean some time ago, which is to hang long, padded, fabric banners on the columns facing the altar, invisible as people enter the nave, which would absorb some of the sound. As yet, nothing has been done.