Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Cold War Fighter Jet Collision Over Guildford

Published on: 24 Jan, 2013

Updated on: 2 Jul, 2023

Further to this website’s request for information and eye witnesses as to the location of the 1952 crash sites, FRANK PHILLIPSON tells the story of the mid-air collision.

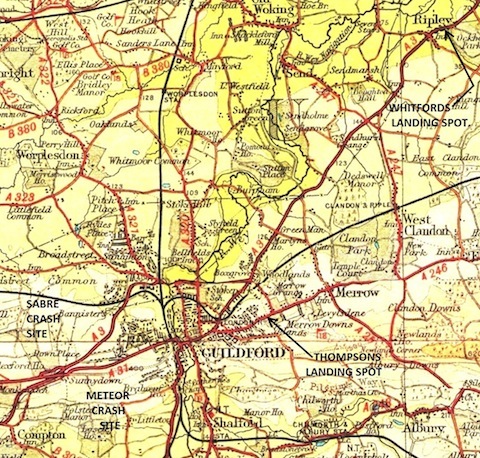

On Monday 5th May 1952 a formation of US Air Force jet fighters acting as “enemy” bombers were being attacked by RAF jet fighters as part of a joint exercise. When two of the jets collided at 24,000 feet to the north-east of Guildford, the town narrowly escaped disaster.

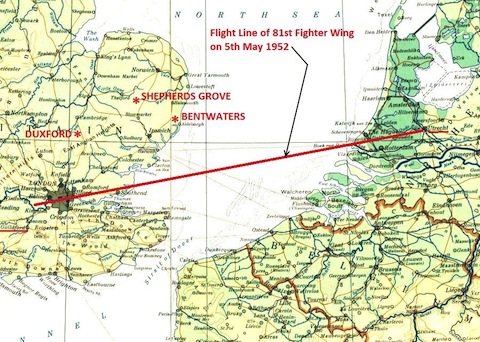

The American aircraft were 32 North American F86A Sabre single seat fighters of the 81st Fighter Interception Wing (FIW) based at RAF Shepherds Grove nine miles north-east of Bury St. Edmunds and at RAF Bentwaters, ten miles east-north-east of Ipswich, both in Suffolk.

The USAF Sabres were sent to the UK in late summer of 1951 to be under the control of RAF No.11 Group, Fighter Command in defence of south-east England at a time of heightened east west tension caused by the Korean War. The F86A was the first swept wing jet in operational allied service and was the only allied aircraft capable of countering the recently introduced Russian Mig 15 fighter jet.

The 81stWing was comprised of the 91st, 92nd and 116th Fighter Interceptor Squadrons (FIS).

The 116th took off with twenty five F86A Sabres from Geiger Field (Spokane Municipal Airport), Washington State on the 13th August 1951. They flew in stages across America and then over the Atlantic via Greenland, Iceland and Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis. They landed at Shepherds Grove on the 27th August.

The 91st and 92nd took off with fifty F86A Sabres from Larson Air Force Base at Moses Lake, Washington State on 11th September 1951. They flew the same route to Stornoway. The 91st left there and landed at RAF Bentwaters on the 2nd October and the 92nd left and landed at RAF Shepherds Grove on the 3rd October. The headquarters of the 81st Wing was located at Bentwaters.

On the 5th May 1952 the 81st FIW was briefed to fly to Utrecht in Holland and then back across the North Sea acting as Soviet bombers with their target being London. They were to fly at 25,000 ft. at a speed of Mach 0.6 (approx. 418 mph at 24,000ft).

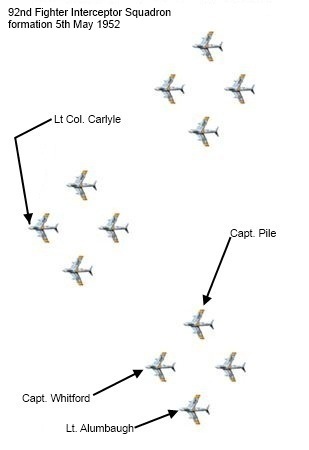

The 92nd FIS with twelve aircraft was to lead with three flights in a ‘Vee’ formation. Each flight of four aircraft was to fly in a diamond pattern with 200ft between aircraft and 500 to 1000ft between flights.

The 116th’s twelve aircraft were to fly in the same pattern to the right and lower than the 92nd. The 91st, with just eight aircraft, were to fly a similar formation to left and higher than the 92nd.

Once the Squadrons had rendezvoused over Holland, the commander of the 92nd Lt. Col. James H. Carlyle led the whole formation as Red flight leader. Behind and to his left was Capt. Milton Gray Whitford leading the second four aircraft flight of the 92nd as “Bouncing White Leader” (White 1).

Whitford was an experienced airman having acting as a co-pilot on five bombing raids over France, Germany and Czechoslovakia in 1945. This was with the 427th Bombardment Squadron of the 303rd Bombardment Group USAAF flying B17 Flying Fortresses from RAF Molesworth, Cambridgeshire.

Whitford and his flight took off from Shepherds Grove at 15:30hrs. His F86A Sabre was serial number 49-1311.

Having met over Utrecht the large formation of F86A Sabres was forced to fly at 30,000 ft. because of a layer of cloud at 25,000 ft. As this dispersed they gradually descended to their briefed height.

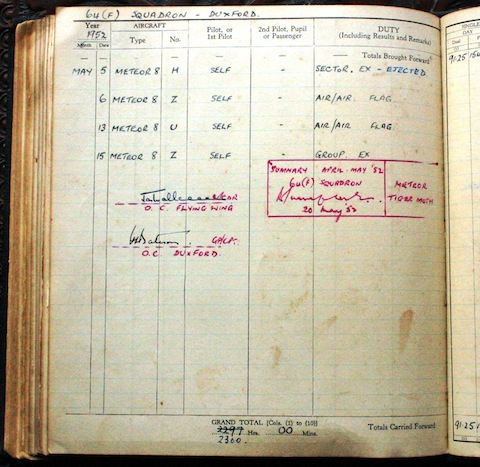

At RAF Duxford in Cambridgeshire, No.64 Squadron, part of the Duxford Wing with No.65 Squadron, were scrambled to intercept the incoming “bomber attack”. With three other Wings, the RAF fighters climbed to carry out attacks on the intruders as part of a Ground Controlled Interception (GCI) exercise. All the fighters were single seat Mk.F8 Gloster Meteor twin engine jet fighters.

Leading No.64 Squadron was their commander Squadron Leader Peter Douglas ‘Tommy’ Thompson. He qualified as a pilot in August 1940 and took part in the Battle of Britain where he shot down three enemy aircraft. He flew in the defence of Malta and then in North Africa, Italy and North West Europe until the end of the war.

Peter Thompson in Spitfire XVI prob TE330 in late 1950s.

While station commander at RAF Biggin Hill in 1957, Thompson formed the RAF Historic Aircraft Flight with three Spitfires. This later evolved to become the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. Courtesy Mimi Thompson.

He took off at 15:55 from Duxford leading three pairs of Meteors. His aircraft was serial number WE929 with the aircraft code letter ‘H’. Thompson’s wingman was Flight Lieutenant Jackson.

Approximately half way across the southern North Sea, about forty Meteors intercepted and started making attacking passes on the American formation. The Sabre pilots described the attacking Meteors as swarming all over them in repeated attacks which continued all the way to the Sabre’s target of London.

Near Heathrow airport, Lt. Col. Carlyle ordered the formation of Sabres to make a right turn to the north to start their return to their bases.

Capt. Whitford dropped his flight down and entered a gentle bank to the right. As he did so he looked around and saw two Meteors coming in from his 5 o’clock position. It seemed to him that they would have seen him so he turned back to watch his leader and continue the turn. A moment later out of the corner of his eye he saw two Meteors almost directly above and overtaking him. They were also in a right bank so that the bellies of their aircraft were toward him making it impossible for their pilots to see him.

They were so close that he knew they were going to collide. He later recalled “I swear that the wings stretched from one side of the horizon to the other”. Realising that the collision was now inevitable he pushed his microphone button and yelled “Look out” for the benefit of the rest of his flight. At the same time he ducked his head down into the cockpit. The time was 16.30hrs.

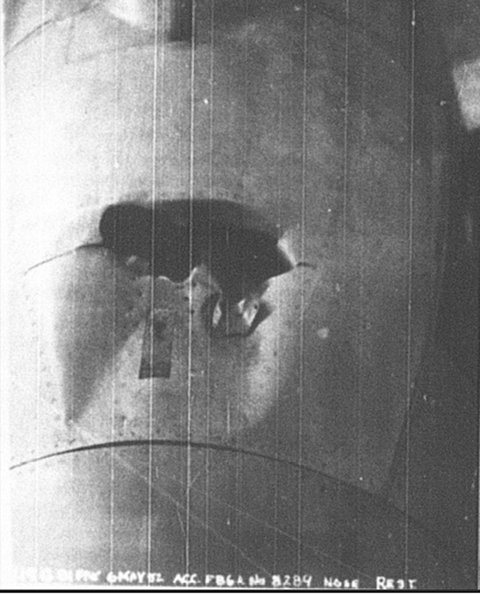

At that moment the tail of the lead Meteor hit and removed the nose and canopy of the Sabre which immediately caught fire. Whitford felt a sudden blow which pushed his head down further. His helmet, which was ripped off by the airflow after the collision, when later recovered, had a split up the rear of it. At the same time he lost his oxygen mask. The violence of the collision seemed to him as if it was head-on. He heard metal scraping and tearing and was finally left sitting in the remains of his now frontless cockpit at a speed of over 400mph at 24,000ft.

From the point when his head had been pushed further down at the moment of collision, he found that he couldn’t see. He had the sensation that everything in front of him had been ripped away and that it felt as if there were flames licking over his back. At the time he was not certain that they were flames. His loss of vision was actually due to blood from cuts on his face getting into his eyes. These cuts had been caused by broken Plexiglas from when his canopy had shattered.

Knowing that he quickly had to escape, he reached down and felt for his safety belt which he had to hunt for in a fraction of a second. Finding and releasing it, the airflow just sucked him out without hitting anything. He was now out in clear air.

Some of his fellow pilots from the following squadrons later told him that all of a sudden they had watched as a body had come flying back between them.

Whitford then wondered if he still had his parachute and reached behind with his left hand to find it still there. He then started to feel for the rip cord. Finding it with one hand he was about to pull it when he suddenly remembered that if he was still travelling forward at the speed of the aircraft it would rip the parachute to bits if he opened it. He very strictly yelled at himself “No”!

He needed to wait until he had slowed down and was falling. Having done this he proceeded to pull the rip cord with little trouble but wasn’t expecting the ‘D’ ring and wire of it to come completely away in his hand! The parachute opened correctly after 10 to 15 seconds with very little if any shock.

He now cleared his eyes and then remembered his bale out oxygen bottle. At great heights there is very little oxygen and to stop from passing out you need to have an oxygen supply. Reaching round he found the bottle, unclipped the hose, put the tube in his mouth and pulled the release on the bottle.

Feeling his face he found it caked in blood although he was unable to discern any large cuts. The airflow now that he was descending seemed to have dried up the blood. He checked his arms, legs and body and moved around deciding that everything seemed to be normal.

Soon he realised that his hands and lower arms were freezing. He wasn’t wearing gloves and had his sleeves rolled up. At the heights that he was at the air temperature was well below zero. From this he suffered mild frostbite to both hands.

As he was floating down he could see the parachute of the Meteor pilot about 8,000 ft. below. Feeling that it seemed as if he would be floating for a long time, he tried to make his descent more rapid by pulling on the risers up to the parachute to side slip it and thereby spill out more air. However, his hands were so cold and the risers so slippery that he couldn’t grip them to control the parachute.

He looked down and saw his watch and decided to time how long his decent would take. He decided that it had been about five minutes since he had baled out. Consideration as to how he would land now came to mind and he tried to remember all he had been taught.

The dingy still attached to his harness was very heavy and the consensus of opinion amongst the pilots was that it should be jettisoned if coming down over land. With considerable trouble he tried to undo its buckles and when that failed he unzipped the dingy bag. Managing to pull half of the dingy out it still seemed hooked up. Further pulling and moving about finally freed it and it dropped but didn’t fall away as its safety line was still attached to him. Pulling it back up to him he unfastened the line but didn’t let go of it as he had just started to descend through cloud. Coming out of the cloud he checked that there was a clear field below him and let the dingy fall away. It landed about a quarter to half a mile away from where he eventually landed.

About this point he started to stick his hands up under his Mae West life jacket now and then to try and warm them. It went through his mind that he would like to have a ‘last’ cigarette. However he had none in his flying suit and even if he had it would be difficult if not impossible to light and smoke it. He tried to pick out the field he would land in and one after the other they past under him and he continued to float onwards.

Frustrated by this he decided to have another go at side slipping his parachute to reach the ground more quickly. He was now able to grasp the risers and pulling on the ones on the right he managed to start to spill out air from his chute. Suddenly the parachute started to collapse and quickly letting go of the risers decided that he would leave well alone and land where ever the parachute took him.

Having past over so many open fields Whitford now looked up as he neared the ground at 300 to 500 feet to find that he was descending right into the centre of the “little town” of Ripley with all its buildings, chimneys, telegraph poles and trees!

As he got lower he climbed up his parachute lines and pulled his feet up to avoid obstacles as they came towards him. He now seemed to be falling very fast and crossing the High Street he narrowly missed hitting some telephone wires.

He was now heading towards Ryde House, a large detached Queen Anne house, on the western side of the High Street. Passing over a six foot fence he rapidly descended vertically behind trees next to the road and the front of Ryde House toward a grass lawn.

With his hands on his parachute risers and with his knees bent ready to roll he hit the ground but instead of rolling ended up falling face forward on the lawn burrowing a little furrow with his nose. He had landed just a few feet from a glass conservatory on the northern side of Ryde House with his parachute hung over the corner of the house itself. He immediately jumped up and tried to walk around. It had been 19 minutes since he had left his aircraft.

The first person to reach Captain Whitford was John Hutson who had been working in the pharmacy of Whites chemist shop in the High Street. He was alerted that something was happening when he saw people outside the shop looking up into the sky. Going out into the street he saw the pilot land in the garden of Ryde House. Still in his white lab coat he rushed across the High Street and up the driveway of the house, which at that time ran directly up to the front of the building (the driveway now goes up the side of the house).

As a scoutmaster and chemist shop worker he had first aid knowledge and proceeded to help the bloodied pilot. With other people Whitford was helped out of his parachute harness and other flying equipment. After saying that he felt fine and that there was nothing much wrong with him he was persuaded to lie down until the ambulance arrived.

The resident of Ryde House, Mrs Elizabeth Hole, didn’t know that anything was happening. Hearing her dog barking she thought that somebody must be at the front door. Opening it she found Captain Whitford lying to the left with John Hutson attending to him.

The American pilot was then wrapped in blankets and had his face washed to see where he was cut. He had also suffered abrasions to both hands, his left knee and right thigh. Mrs Hole brought him out a large brandy and a cup of tea. After his brandy and while sipping his tea, the ambulance turned up. This was some ten to fifteen minutes after he had landed. Whitford was loaded into the ambulance and taken to the Royal Surrey County Hospital in Guildford where he was kept in overnight for observation.

Shortly before the collision, Squadron Leader Thompson together with his wingman had already completed six or seven attacks on the formation of American fighters. Commencing another attack on the starboard side he saw the F86A formation start to make a turn to starboard. He broke off his attack and attempted to make a hard climbing turn to starboard to rejoin his Wing leader above. At that moment he felt a crash in the rear of his aircraft.

As the aircraft started to spin he tried to regain control but could not get any response from the controls. The collision had in fact removed the whole tail section of his Meteor. With the cockpit still intact he remained with the aircraft until at a lower height, but with it now uncontrollable, he had no option but to jettison the canopy and activate the ejection seat. He made a good exit from the aircraft and his parachute opened correctly.

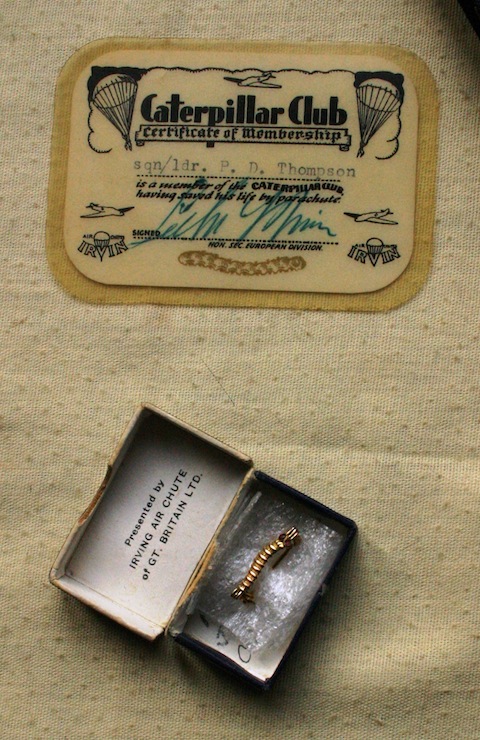

Peter Thompson’s Gold Caterpillar Club Badge awarded by the Irving Air Chute company for a successful escape from an aircraft using one of their parachutes. This badge has red jewel eyes indicating escape from aircraft on fire.

Coming into land he just missing a house and then gently landed on the grass verge of Epsom Road, Merrow, Guildford near to a road called Gateways. Motorists stopped their cars and went to help him together with local residents. However he was completely uninjured. He told the small crowd that had gathered round him that some other aircraft had crashed into him and taken his tail off. He asked where the nearest RAF airfield was so that he could get an aircraft back to his base.

Not long after this the St. John’s ambulance arrived having responded to the numerous 999 calls. It conveyed the uninjured pilot to Guildford Police station in Guildford.

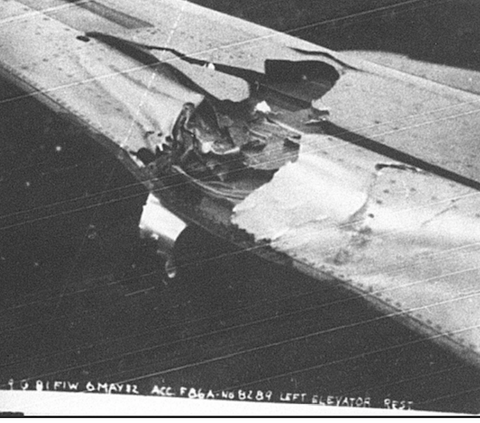

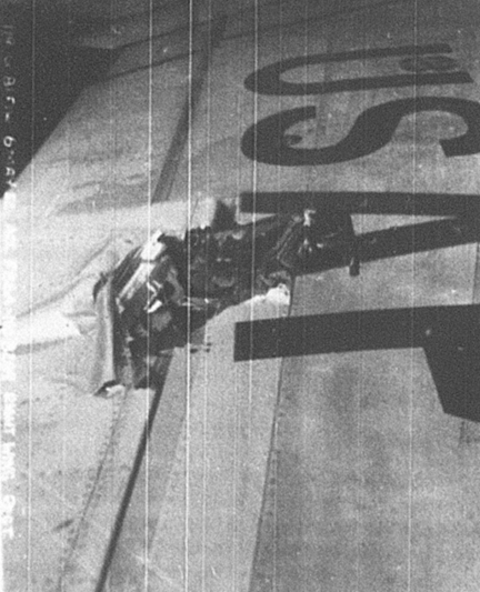

At the moment of collision Whitford’s wingman, 1st Lieutenant Lester Alumbaugh (White 2), was flying to the left and behind his leader. He saw the Meteor at the last moment and didn’t have time to call a warning. The impact of the collision caused pieces of the two aircraft to fly back and hit Alumbaugh’s Sabre causing major damage to the right wing and the left horizontal stabiliser/elevator. There was also minor damage to the front fuselage, windshield and left wing. Alumbaugh immediately concentrated on getting away from his leader’s aircraft which was falling back into the path of his own aircraft.

He executed a left turn away from the burning aircraft but realised that his aircraft had been badly hit. He didn’t know how bad the damage was and could feel jolts from the aircraft. After a few seconds he found that he still had good control of the aircraft at stalling speed. Reassured by this he flew back to his base at RAF Shepherds Grove and made an uneventful landing.

Moments after the collision, Lt. Col. Carlyle received the information that a Meteor had collided with Capt. Whitford’s Sabre. He detailed White 3 (Capt. Pile) and White 4 to remain at the scene to see that Whitford had parachuted safely. Capt. Pile had seen Whitford leave the aircraft and his parachute open at 19 to 20,000 feet. He circled the parachute until it entered cloud at 2,500 feet. Letting down through a clear area he was unable to see it again at which point he had to return to base because he and his wingman were running low on fuel.

Lt. Ernie Pile, 92nd Fighter Squadron, F86A Sabre. USAF Photo Via David W. Menard at Wikimedia Commons.

Nothing was heard from Lt. Alumbaugh until two minutes after the collision when he called in to say that his aircraft had been hit by debris from the collision of the two aircraft. Carlyle detailed Blue 3 to look after the damaged aircraft in an effort to establish the extent of the damage and to escort it back to base.

81st Fighter Wing Reunion 2003. Front Centre, Les Alumbaugh, Right Front, Milton Whitford, 2nd from left rear, Seldon (Ernie) Pile. Courtesy Whitford family.

Capt. Whitford’s burning aircraft came straight down and buried itself in a field of rye half a mile south of Wood Street Village just south of the Guildford to Aldershot railway line on the land of Blackwell Farm. It left a crater approximately 30 feet in diameter with little left to see above ground. As the local fire brigade attempted to tackle the burning aircraft wreckage there were many explosions and the police kept onlookers back. Despite the efforts of the fire brigade the remains continued to burn far into the night. Small parts of both aircraft that became detached during their decent were scattered over a wide area.

The Sabre came down just as children were leaving Wood Street village school. Many of them rushed to see the crashed aircraft but were kept back until police arrived by a lady who rushed out from her house in just bedroom slippers.

Sqdn. Ldr. Thompson’s Meteor crashed into trees in East Warren woods on the Loseley House Estate, one and a half miles south west of Guildford. A dense pall of smoke rose above the trees and police cordoned off the area. One of the wings came down in a field on the southern slope of the Hog’s Back the other on an area of sand east of the ruined St. Catherine’s chapel. Part of a fuel tank from the Meteor damaged the roof of a house in Pewley Way half a mile east south east of Guildford.

A number of school boys at the time saw the collision and visited the crash sites.

Rob Long lived on a hill in Park Barn Drive half a mile east of the Sabre crash site. His father, who was on duty with the Royal Observer Corp at the post on the Hogs Back, telephoned home to his mother. He said to let Rob know that there was an RAF/USAF exercise taking place and to look out for it.

Outside Rob and his friends were just able to make out the formation at high altitude. They saw a puff of smoke appear within the formation which was the collision. Soon debris was falling and fluttering down all over the area. They briefly caught a glimpse of the Sabre, which seemed to still be under full power, before their view of the ground was blocked by a hedge and they felt a huge thump as it buried itself into the ground.

They jumped on their push bikes and cycled towards Wood Street. Nearing the location of the crash they were stopped from proceeding by the police. Skirting around from this they observed the crash site from other vantage points.

In the next few days the USAF and the RAF arrived to recover the wreckage of their respective aircraft. Rob found that the USAF posted a rigid guard around the crash allowing no one near especially not young boys. At the Meteor crash site the RAF airmen were somewhat more laid back. As they sat around brewing up a pot of tea the boys were told they could go and look at the Meteor wreckage but not to touch anything.

David Bailey visited the Sabre crash site after the USAF had left and says that there were numerous school boys collecting small bits of the aircraft from the field.

Terry Flack saw the crash site of the Sabre and says that it just left a massive hole in the ground. On a school cross country run the next day the route took them on the south side of the Hog’s Back where he saw the wing of the Meteor lying in the field and the wreckage in the trees. He later managed to find a small pneumatic valve from the Sabre which he still has.

Malcolm Richardson was 15 at the time. He witnessed a large puff of smoke rising from where the Meteor had crashed from his garden in Farncombe, one and a half miles to the south. Visiting the site a few days later on his push bike he found that the aircraft had smashed into a dense area of pine trees. It was here that he found a spent shell casing which had gone off in the fire caused by the crash.

At the Royal Surrey County Hospital in Guildford, Captain Whitford was checked over, cleaned up and put on a ward with other local patients. He was visited by John Hutson from Ripley. Later he was sitting chatting to the other patients when a nurse came in and said he really ought to get some rest. Shortly after a doctor came in and said that he needed to give him an injection. Whitford didn’t ask what it was for and didn’t think further about it.

At Shepherds Grove, Elizabeth Whitford was at home making the evening meal. When Milton didn’t turn up she thought to herself “is he at the bar? Well I’m having dinner”. Shortly after starting there was a knock at the door which proved to be one of the officers who said: “Lizzie, we have a problem. Whit’ has had an accident but he’s OK. Come with me and we will give him a call.”

Milton Whitford was home the next day and was soon passed fit to resume flying. Sometime later he was sitting at work one afternoon when he started to itch and within fifteen minutes he had swollen up and his skin was on fire. It was due to the injection he had been given. It turned out that he had been given a raw tetanus serum injection, which he had already had, and should only have been given a tetanus booster. The reaction had him laid up for three or four weeks and it stayed with him for years affecting his joints.

At Duxford, Mimi Thompson received a call from the Squadron to say that Peter was delayed as he had landed at Farnborough with no mention of an accident. When he eventually got home in the early hours of the morning still in his flying gear she thought he was joking when he said he had ejected after a collision with another aircraft. It was only in the morning when she read the newspaper that she realised he had been serious.

On the 8th May 1952 the USAF held an Accident Inquiry (Board of Officers) in the Wing Operations Room at RAF Duxford. All the US and RAF pilots involved in the incident or nearby gave evidence. The findings were that the Meteor pilot had not kept an adequate view of all the aircraft in the US formation.

Recommendations were made that simulated “bomber” formations be kept to just twelve aircraft with greater distances between flights and attacking aircraft to make attacks in smaller flights to reach their target aircraft in waves rather than a mass formation.

The cost of the written off Sabre was quoted in the report as $185,105.00.

After the inquiry Milton Whitford met Peter Thompson who took him to the Duxford officer’s mess for a couple of drinks. Milton later told his family that Thompson was “a hell of a nice guy and I liked him a lot”.

A later RAF Court of Inquiry came to a different conclusion and found that the cause of the accident was due to the fact that the formation of Sabres “carried out almost a crossover turn which they were not expected to do”. It concluded that neither of the pilots could “be considered blameworthy”.

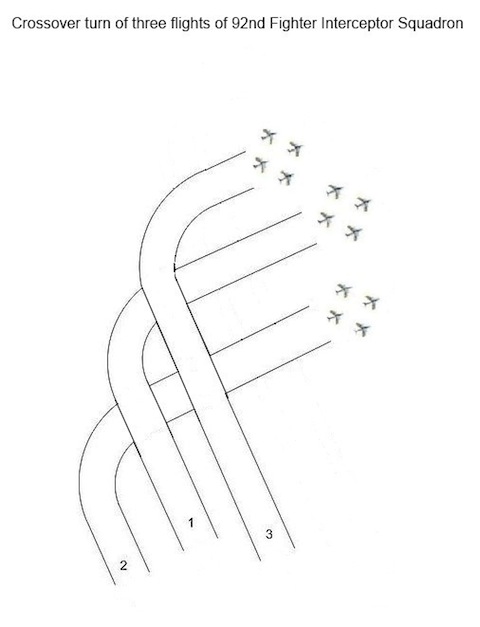

A cross-over turn is used to avoid having to keep adjusting speeds and power settings of the three flights of a formation such as that of the 92nd Squadron. The flight on the left would drop down and pass under the lead flight and come out of the turn on their right. The flight on the right would climb above the lead flight and come out of the turn on the left of that flight (see diagram).

In his statement after the accident Whitford says that during the turn to starboard he started “to drop down about 200 feet in case I needed to cross under the lead flight”. In his evidence at the inquiry he talks about “dropping down just a little bit” and “hadn’t started to cross over”. No other pilot, either British or American, talks about a cross-over turn in any of their statements or evidence that appear in the USAF Accident Report.

It may be that the US Inquiry, held only three days after the incident occurred, did not pick up on this point. With the RAF Inquiry (records of which no longer exist) held later, there may have been evidence that came to light from pilots who where further away and not immediately involved. They may have possibly been able to get a better overview of what occurred.

The collision seems to have been regarded by both air forces as something like a modern day motor racing incident, where things unfortunately occur for a split second in the heat of the moment. As Milton Whitford later remarked: “It was not that uncommon for planes to come together [then]. Every month you would hear of someone being lost.”

Responses to Cold War Fighter Jet Collision Over Guildford

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Please see our comments policy. All comments are moderated and may take time to appear. Full names, or at least initial and surname, must be given.Recent Articles

- City Succumbs to Penalty Equaliser in the Eleventh Minute of Stoppage Time

- Letter: Who Will Defend Guildford’s Allotment Holders?

- Updated: Accident Closes Portsmouth Road Diversion Route

- Upgrade for Spectrum Under Confirmed £10m Leisure Facility Contract

- The Ultimate Beatles Show – The ‘White Album’ On Stage, Note For Note

- Letter: Name-calling Won’t Solve GBC’s Housing Maintenance Issues

- Highways Bulletin: Smarter Traffic Lights, Smoother Journeys

- Birdwatcher’s Diary No.332

- Police Seek Information After Delivery Rider Assaulted

- Mayor’s Diary: August 3 – August 30

Recent Comments

- Fred Clarke on Lots More Pictures of 1960s George Abbot Pupils: Are You Among Them?

- Jan Messinger on Pay Rise for Joint Guildford-Waverley CEO Agreed

- Stephanie Webster on Letter: Many Residents Unhappy with Plans for Guildown Roadworks

- Susan Smith on Birdwatcher’s Diary No.332

- Mayonne Coldicott on Borough Council Hears Plea To Take a Moral Stand Over Gaza

- Jim Allen on Pay Rise for Joint Guildford-Waverley CEO Agreed

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

John Carr

February 24, 2013 at 2:34 pm

Thanks for such a thorough and well written article.

Ned Neill

February 28, 2013 at 1:56 pm

As a former RAF pilot who flew the F86 in Germany in the early 1950’s I am much impressed by this well written and researched piece. Such is the level of detail I wonder when it was written?

My interest stems from the fact that I am currently involved in researching an incident in which two of my fellow squadron pilots lost there lives in Feb 1954 and I am particularly interested to note that having quoted from the Findings of the Court of Inquiry the author later mentions that these records “no longer exist” which might explain the difficulties I have experienced in gaining access to official records.

I would be most grateful if you could ask Mr Phillipson to contact me in the hope he might be able to help with my research.

Thank you.

David Williamson

March 18, 2013 at 11:21 pm

A well researched article covering all avenues, backed up by good documentary evidence. An interesting read.

Col. Arlie J. Blood (ret)

May 6, 2013 at 11:22 pm

I was Wing Operations Officer during this time period and remember this incident well.

Please pass best wishes to “Ditty”, Arlie and Lucille Blood.

Tracey Broome

November 16, 2013 at 1:42 am

I have just come across this article. I worked with Gray (Milton) Whitford in the 1980’s, he gave me my first job out of college, and I have never known a finer man. I miss him terribly! We travelled together all the time and I have heard this story over dinner and margaritas many many times.

He taught me so much and I will never forget him.

Robert Beasley

August 30, 2015 at 7:24 pm

In 1952 I was at Henley Fort school camp at the top of the Hog’s Back (51 13 48.19N 00 35 46.97W). We were playing football at this point and heard a strange noise. Looking up, the Meteor passed just above our heads by no more than 20feet. We were too stunned to be alarmed as it all happened in a flash. It was upside down and I saw inside the empty cockpit very clearly.

I don’t remember the tail missing but do remember that both engines were in place and I do not recall either of the wing tips missing (contrary to above). After a few seconds it went into the woods just to the south of us and we all (about 20 of us) dashed to the scene – you know what 12-year-olds are.

Tearing through scrub and woodland we came across the smoking wreckage and a few souvenirs were taken. We were perhaps a little sad not to find a body! That evening the RAF turned up at Henley Fort and we were all lined up in the main courtyard and made to hand over our souvenirs. I’m not sure that all were handed over. We were on the scene within perhaps two minutes, so were the first there (again contrary to the comments above).

Peter Arthur

November 21, 2016 at 11:39 am

Fabulous article.

I have been searching for this information for about 20 years, as I found the tail section of the Meteor behind the Guildford Rowing Club. I took it home to Castle Street on an old set of pram wheels, where it remained for several weeks until my mother persuaded the dustman to remove it.

I also found what I think was the tail light. This was on the towpath on the other side of the river about 100 yards away.

Frank Ayling

December 26, 2024 at 4:44 am

I have just come across this article and was amazed to read it as it is part of my life’s story. I was a child who lived in Merrow Street in the 1950s. One day when I was seven years old, I was sent to get my mother cigarettes something I often did.

Shortly after leaving my house, No 1 Alma Cottages, opposite the old Great Goodwin Farm, I met up with the cowman from the farm bringing in the cows for milking. He stopped me and said: “Son, look at that piece of paper floating down from the sky why don’t you try and catch it?” So I said: “Yes!” and then ran across the field to a duck pond and stood there looking up to catch it. My mother who must have seen me and came out of the kitchen and grabbed me.

As far as I can remember, it wasn’t paper but parts of an aircraft and landed in the pond. I remember police came to our house to investigate and look for the debris. It must have been the same incident.

Frank Ayling

January 14, 2025 at 12:03 pm

My email address if anyone wants to contact me regarding the above comment is Fayling5@gmail.com.