Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Milestones in Rock ‘n Roll History: Eric Clapton And The ‘Beano’ LP

Published on: 28 Sep, 2018

Updated on: 28 Sep, 2018

It became known as ‘the Beano album.’ Dave Reading continues our series on Milestones in Rock ‘n’ Roll History by taking a look at the 1966 recording session that defined British blues.

When Eric Clapton (who grew up in Ripley) walked into the Decca recording studios in March 1966, he had the self-confidence of a man who thought he owned the place. He was there to record with one of the giants of British blues, John Mayall, but if Clapton was over-awed he didn’t show it. As the producer looked on in amazement, Clapton took control.

It was a decisive moment in the history of rock music. Clapton developed a technique and a sound that changed the way the electric guitar was played. For years to come, you could put on a rock or blues album, or walk into a pub where a live band was playing, and you would get a flashback to Eric Clapton in his 1960s period. On just a handful of songs on one album – Blues Breakers, released in July 1966 – Clapton plotted the direction followed by rock and blues guitarists for years to come.

“The guitar player suddenly became the most important guy in the band,” said Steven Van Zandt of Springsteen’s E Street Band. “He (Clapton) turned the amp up to 11. That alone blew everybody’s mind in the mid-Sixties.”

Minds that were blown included those of Angus and Malcolm Young of AC/DC. Listening to Blues Breakers formed a key part of their musical education when they were in their teens. The late Paul Kossoff, barely 16 at the time, also noticed what was going on. He’d given up on the guitar but returned to it when he caught a Mayall-Clapton live show. As a founder of Free, Kossoff went on to be one of the most gifted, flamboyant guitarists of the late sixties.

Blues Breakers was recorded over three days at the Decca studios in West Hampstead. Throughout the album Clapton’s guitar screams out at high volume. He played through his Marshall amp exactly as he did on stage and the effect was stunning.

As the first track begins, you hear a single drum beat followed by a ferocious ‘double stop’ – the term for the act of playing two notes simultaneously – sliding up the neck of the guitar. From the start, Clapton’s guitar is centre stage. And there he is in the background, too, playing a separate, distinct rhythm part. This is the opening track, All Your Love, a Chicago blues in a minor key written and recorded in 1958 by Otis Rush.

After a couple of verses, the pace quickens and we’re in a major key: it’s Clapton again with one of the album’s most memorable solos. Mayall continues with the chorus, and then we’re back with the solo Clapton opened with.

In his autobiography, Clapton explains how he found his sound, using a combination of his Gibson Les Paul Standard guitar and his amplifier to produce a rich, thick-textured sound.

“I insisted on having the mike exactly where I wanted it to be during the recording, which was not too close to my amplifier, so that I could play through it and get the same sound as I had on stage. The result was the sound that came to be associated with me. It had really come about accidentally, when I was trying to emulate the sharp, thin sound that Freddy King got out of his Gibson Les Paul, and I ended up with something quite different, a sound which was a lot fatter than Freddy’s.”

He had the amp and guitar turned up to full volume so everything was on overload. He would hit a note, hold it and give it some vibrato with his fingers, until it sustained, and then the distortion would turn into feedback. This was how the Clapton sound was created.

Rock music author Dave Thompson wrote that even Mike Vernon, producer of the album, was taken aback. He and engineer Gus Dudgeon were desperately trying to figure out how they could capture the sound of Clapton in full flight. “Feedback, leakage, distortion, Clapton didn’t care what he wrought on the hapless recording equipment, just so long as it felt right,” said Thompson. “Clapton’s guitar screams out, a barrage of beautiful noise more shattering than any which had ever been preserved on a British blues record.”

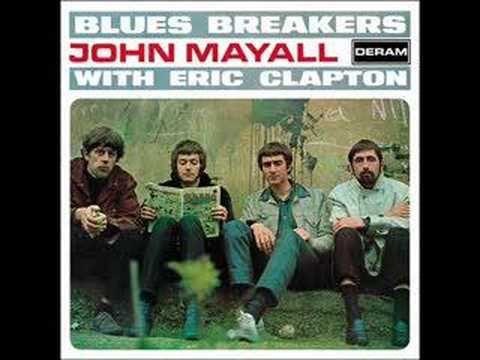

Cover of the Blues Breakers album with Eric Clapton pictured second from left. It has become known as the ‘Beano albm’ as Eric is pictured reading the famous comic.

Clapton’s arrogance was also evident during the promotional work for the album. “On the day we had to have the photoshoot taken for the cover,” he said, “I decided to be totally uncooperative, since I hated being photographed. To annoy people I bought a copy of the Beano and read it grumpily while the photographer took the pictures.” So the Beano picture wasn’t the carefully-staged promotional stunt that people imagined it to be.

As All Your Love ends on a minor chord, Clapton in full flight again, delivering an instrumental showpiece called Hideaway, adapted by Freddie King around 1960 from an earlier piece by Hound Dog Taylor. The piece features some exquisite blues guitar phrases that have been mimicked many times since Clapton made it famous.

During the mid 1960s, pop music was a dazzling creative force. In parallel, blues was set to cause an explosion of its own. Soon after Blues Breakers, right through to the end of the 60s, British audiences could hear the wonderful sounds of Peter Green, Savoy Brown, Free, Aynsley Dunbar, Ten Years After, Chicken Shack and many others. It was Blues Breakers that led the way.

When asked if he could remember the first piece of blues he’d heard, Gary Moore said in an interview with Guitarist in 2004: “Yeah, I can, it was the first track on the Blues Breakers with Clapton album: All Your Love. What a first thing to hear!”

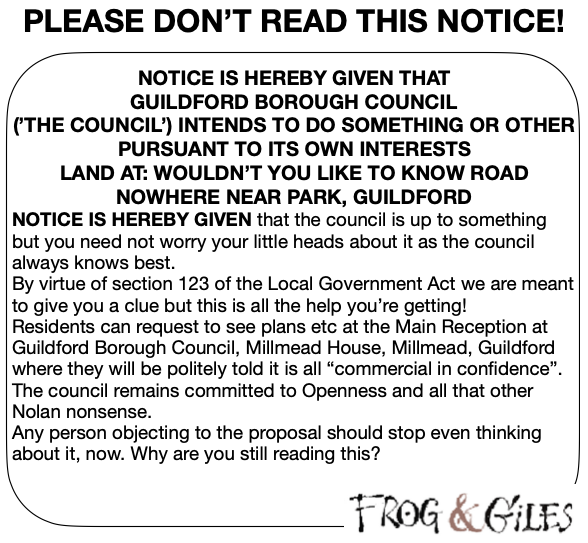

See Dragon story: GBC’s Explanation of Major Land Sale Notice Error ‘Borders on Arrogant’ Says Councillor

Recent Articles

- Drug Gang Jailed: Their Activities Were Directed From Behind Bars, Court Told

- Planning Inspector Allows Another High-rise for Woking

- Letter: Why These False Flag Political Stunts?

- Highly Regarded Joint Strategic Director Quits Guildford & Waverley Councils

- Birdwatcher’s Diary No.302

- Diocese of Guildford Appoints New Registrar and Legal Advisor

- ‘One in Five’ Surrey Police Officers Seeking Another Job

- Insights: Lead from the Front on Values

- New Investment Will Help Surrey Fire and Rescue Service Improve Training Facilities

- Letter: Are the PCC Candidates Relying on Their Party Labels?

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments