Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Abraham Lincoln

If given the truth, the people can be depended upon to meet any national crisis...

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Guildford news...

for Guildford people, brought to you by Guildford reporters - Guildford's own news service

Tumbling Bay’s Original Use And Why The Mill Stream Could Date To Saxon Times

Published on: 10 Nov, 2019

Updated on: 12 Nov, 2019

The collapse of the Tumbling Bay weir at Millmead in Guildford and the unusual sight of a trickle of water on some stretches of the navigation towards St Catherine’s has led to questions about the age of the weir and also that part of the waterway.

The Tumbling Bay weir washed away. Photographed on Monday, November 4, 2019. Click on all pictures to enlarge.

It may come as a surprise to learn that it is likely man has been ‘altering’ the course of the River Wey for good reasons as far back as Saxon times!

The Godalming Navigation looking towards the Weyside pub, Guildford, on November 4, 2019, with a much reduced flow of water.

Here, eminent local historian Dr Mary Alexander, formerly collections officer at Guildford Museum, explains what Tumbling Bay was original created for and gives good evidence of the natural river being physically altered over the centuries and for what purposes.

First, a brief recap on the history of today’s Wey Navigations, managed by the National Trust, to which the waterway was gifted in 1964 by its previous owners the Stevens family.

The waterway from Millmead Lock going upstream to Godalming is the Godalming Navigation. It is, of course, linked to the River Wey Navigation that flows downstream from Millmead to Weybridge where it meets the Thames.

The navigation from Weybridge to Guildford was opened in 1653 to carry cargo and was the brainchild of Sir Richard Weston of Sutton Place. It is one of the earliest rivers in Britain to be made navigable. Its creators utilised navigable stretches of the river where possible, digging canals (or cuts) where elsewhere required.

By the 1720s it carried an average of 17,000 tons of produce per year, generating about £2,000 revenue by its tolls. Later, the navigation was extended from Guildford, past St Catherine’s, to reach Godalming in 1764.

Now Dr Mary Alexander writes about her observations:

The tumbling bay on the river at Guildford is a remnant of an old system of getting boats from the upper level of a river to a lower one (and vice versa) usually where a channel had been made at a higher level to take water to a mill.

Early locks had only one gate, at the top, and to get to the lower level the gate was opened and the boat rushed (or tumbled) through on the flood.

The tumbling bay is shown on the 1739 map of Guildford called the Ichnography, and called the Rowling Bay.

A section of the 1739 map of Guildford called the Ichnography. ‘Rowling Bay’ (now known as Tumbling Bay) is marked and can be seen towards the bottom in the centre. Notice ‘The Town Mills’ are marked at the top. The ‘Keep of the Castle and Ruins’ are marked to the top right. The names given to other fields, yards and parcels of land are well worth studying too!

It was clearly where boats on the river upstream of the mill could get to the natural course of the river, avoiding the mill.

In 1764 the Godalming Navigation opened, with improvements to the course of the natural river between Guildford and Godalming.

The Rowling Bay of 1739 shows that boats were already using the river, but after 1764 it would have been much easier. The Tumbling Bay now presumably regulates the flow of water along this stretch.

The natural course of the river is clearly at the lowest point of the land. A stream runs across Shalford Meadows, which must mark the natural course of the river.

A 1900s picture postcard view taken from Guildford Rowing Club looking downstream when it was a wooden footbridge that spanned the river here linking the towpath to Shalford Road. David Rose Collection.

It flows under the embanked stream near Guildford Rowing Club, and joins the natural river at the pool formed below the tumbling bay.

There is also a small weir letting water into this stream from the embanked section, with a bridge across it.

The embanked stream is clearly taking water to the Town Mill [adjacent to today’s Yvonne Arnnaud Theatre].

The mill site is definitely medieval and could be Anglo-Saxon. The embankment starts as far upstream as St Catherine’s Hill, where the river flows up against the hill and on the edge of the alluvium.

Further upstream, the natural river flows a very meandering course past Shalford, but a straighter channel was cut to bypass it for the Godalming Navigation.

The straight ‘cut’ at St Catherine’s Lock on the Godalming Navigation. Photographed by Bill Dennett in what looks like the 1930s.

There were two other cuts at Unstead and Catteshall, but not at St Catherine’s, which must have been a satisfactory channel already.

So when was this stretch [St Catherine’s to Millmead] embanked? As it provides a head of water for the mill, it must be of the same date, and therefore could be as early as Saxon times.

However, we have very little information before the 18th century, so we must be cautious.

Large scale water-works are known from Saxon times, so there is no reason why the mill stream could not be Saxon, but we don’t know what alterations may have been made in the following centuries.

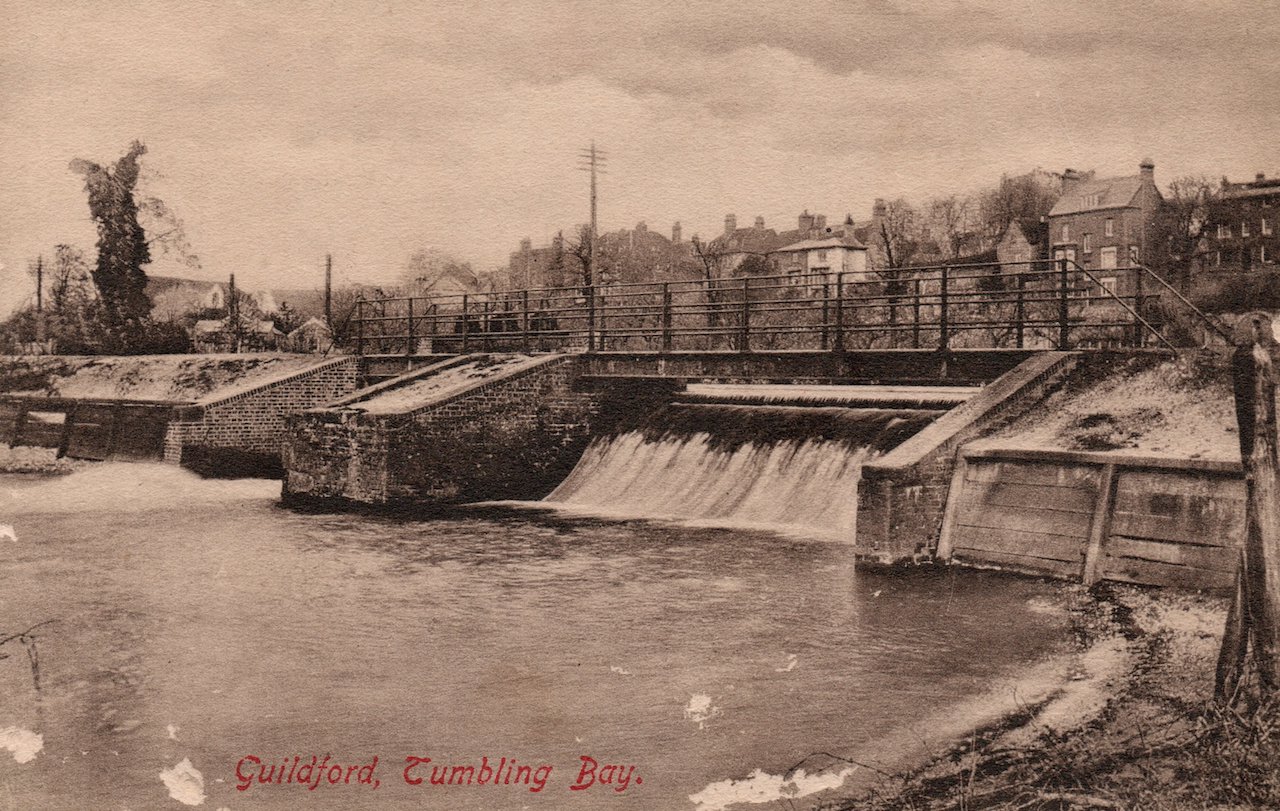

Water, water everywhere! Viewed from Quarry Street, Tumbling Bay in the floods of 1910. David Rose collection.

The parish boundary between St Mary’s and St Nicolas follows the natural river from the Town Bridge south, then turns up the tumbling bay and along the mill stream.

This suggests that the mill stream is very old, since parish boundaries were being fixed in the 11th and 12th centuries, but probably earlier at Guildford.

Guildford was established as a planned town in the mid-10th century and the parish boundaries were probably defined then.

The boundary continues south, dividing Shalford from Artington, along the embanked stretch then returning to the natural river.

See Dragon story: GBC’s Explanation of Major Land Sale Notice Error ‘Borders on Arrogant’ Says Councillor

Recent Articles

- Guide to Telephone Befriending Services for Older People

- Stage Dragon: Sleuth at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre

- Guildford Lido All Set for the 2024 Season

- Appointment of Permanent Joint Strategic Director of Finance Confirmed

- Police and Crime Commissioner Candidate Interview – Alex Coley

- New Approach to Mental Health Concerns Reported to the Police

- Letter: Bernard Quoroll ‘s Insight Should Be Heard

- Police and Crime Commissioner Candidate Interview – Paul Kennedy

- Staff Union Warns Surrey University of No Confidence Votes

- Invitation to Join Mass Bike Ride on Saturday, April 27

Search in Site

Media Gallery

Dragon Interview: Local Artist Leaves Her Mark At One of England’s Most Historic Buildings

January 21, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: Lib Dem Planning Chair: ‘Current Policy Doesn’t Work for Local People’

January 19, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreA3 Tunnel in Guildford ‘Necessary’ for New Homes, Says Guildford’s MP

January 10, 2023 / No Comment / Read More‘Madness’ for London Road Scheme to Go Ahead Against ‘Huge Opposition’, Says SCC Leader

January 6, 2023 / No Comment / Read MoreCouncillor’s Son Starts Campaign for More Consultation on North Street Plan

December 30, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreCounty Council Climbs Down Over London Road Works – Further ‘Engagement’ Period Announced

December 14, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreDragon Interview: GBC Reaction to the Government’s Expected Decision to Relax Housing Targets

December 7, 2022 / No Comment / Read MoreHow Can Our Town Centre Businesses Recover? Watch the Shop Front Debate

May 18, 2020 / No Comment / Read More

Recent Comments